For this year’s AAPI Heritage Month, I will take each day to pull one of my favourite posts or pieces from the archives highlighting some aspect of AAPI history and heritage, and add to it a short commentary and reflection. I invite you to check back every day for this #ReappropriateRevisited month-long feature!

Yesterday, I revisited one of my most popular listicles regarding mental health and mental illness within the AAPI community (Mental Health Awareness Week: Top 10 Myths about Asian Americans and Mental Health). This listcle reflects how most of us popularly conceptualize the issue of AAPI mental health: through statistics about high rates of depression and suicide among women and on college campuses. Studies clearly support a focus on subpopulations of AAPI women and youth as particularly at-risk with regard to unaddressed mental illness. However, our persistent framing of the AAPI mental health issue only through these two lenses ignores two other particularly vulnerable AAPI populations: Southeast Asian American refugees and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders.

I remember attending an AAPI conference early in my career as an activist and blogger (which conference it was has long since left my memory) wherein I was first introduced to the need to disaggregate epidemiological data along ethnic lines to reveal ethnicity-specific disparities that specifically impact Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. At the time, all data for AAPI were lumped together, and the relatively small proportion of Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders within our community masked these patterns. At the time of the conference, disaggregated data were rare: now, studies have confirmed alarming public health issues for Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Only when I started writing on the topic of mental health — and therefore read a number of primary source material — did I learn about the scope of this issue.

With regard to depression and suicide, a shockingly high number of Southeast Asian American refugees live with symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Rates of suicide ideation and attempts are significantly higher for Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders — particularly among youth and when compounded with queer identities — compared to the average rate for Asian Americans or the national average as a whole.

Yet, when we talk about AAPI mental health, we rarely ever include in our conversations meaningful discussion about Southeast Asian Americans or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders. Why is that? Is there a certain amount of reinforced privilege in focusing our conversation on AAPI mental health entirely to the exclusion of our Southeast Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander brethren?

Last year, I wrote a post about the high rate of suicide among Bhutanese Americans, which is twice that of any refugee population in the country. As part of today’s effort to highlight mental health issues particularly within Southeast Asian Americans and Native Hawaiian & Pacific Islanders, I’d like to revisit that post for today’s #ReappropriateRevisited.

Suicide rate of Bhutanese Americans twice national rate, highest among any refugee population

Despite the precepts of the Model Minority Myth, not all Asian American & Pacific Islanders (AAPI) in the United States arrived as wealthy, middle-class East Asian entrepreneurs to pursue graduate degrees or to start small businesses. According to statistics published yesterday by the Center for American Progress, one-fifth of AAPI who received permanent resident status in 2012 did so as refugees or asylees; yet this population — many of whom can trace their ethnic heritage to Southeast Asia — struggles for visibility against the backdrop of the larger AAPI community. This invisibility is exacerbated by the absence of disaggregated data for the AAPI community along ethnic lines, which can reveal the unique sociopolitical iniquities that plague Southeast Asian Americans.

According to the United Nations, America is home to approximately 70,000 Bhutanese Americans, representing less than 0.5% of the AAPI population. Bhutanese Americans are ethnically derived from the small land-locked country of Bhutan, a small country in the Himalayas bordered by the two much larger nations of China and India. In the 1980’s, thousands of Bhutanese were forced out of Bhutan during a period of countrywide political turmoil (many expelled Bhutanese were targeted due to their non-Tibetan origins), and were forced to relocate to temporary refugee camps in the neighbouring country of Nepal; some subsequently accepted permanent relocation to the United States as political refugees starting in 2008.

Currently, the Bhutanese American population is concentrated in several states including Texas, Arizona, and New York. In New Hampshire, the state’s population of 2000 Bhutanese Americans represent 65% of the state’s total refugee population.

And shockingly, our country’s small, young, and underserved population of Bhutanese American refugees suffer among the country’s highest rates of PTSD, depression, and suicide — the latter of which is nearly twice that of national suicide rates — indicating a clear failure of America’s existing healthcare and social services programs to adequately address and support Bhutanese Americans.

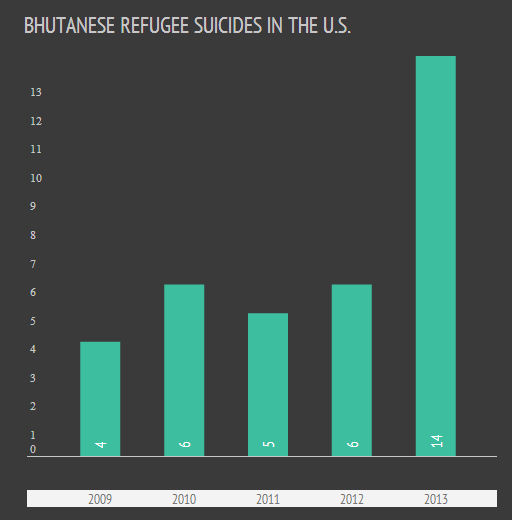

Last year, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued a report specifically examining the suicide rate among Bhutanese Americans. They discovered 16 reported suicides — spanning 10 states — of Bhutanese American refugees in the three years between 2009 and 2012, which translates into a startling suicide rate of 20.4 deaths per 100,000. By comparison, the national suicide rate in America is 11.5 deaths per 100,000.

In other words, the suicide rate for Bhutanese Americans is nearly double that of the national average, and is the highest reported suicide rate of any refugee population in the United States.