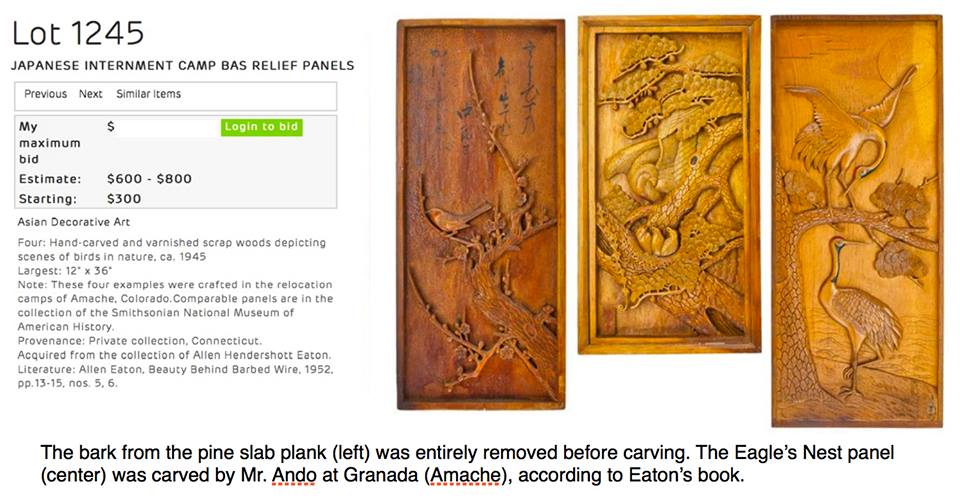

Last week, New Jersey-based Rago Arts and Auction House came under fire with news that they had been consigned by an anonymous seller living in Connecticut to sell a valuable collection of nearly 450 Japanese American incarceration artifacts — most of them commissioned black-and-white photographs and hand-made artpieces created by incarcerees. Many of the pieces were donated to famed art historian Allen H. Eaton with the understanding that he would use them in a public exhibition to draw attention to the injustices of the camp, but not for sale or profit. When Eaton died, the collection was passed down to his daughter before making its way to the family of the anonymous seller who planned to auction the collection piecemeal through Rago on Friday.

As news of the planned sale — which was scheduled for auction on Friday, April 17 — made its way to the public, many within the Japanese American community were understandably outraged. Many within the community (including several who found pictures of relatives, and family heirlooms, within the Eaton collection) spoke out vocally against the sale, which amounted to profiteering off the pain of survivors of American concentration camps. A Facebook-based social media campaign (“Japanese American History: NOT For Sale“) sprung up with the goal of halting Friday’s auction, and to propose an alternative solution to the public sale that would honour the original intent of the collection.

Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation — the group responsible for maintaining the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center at the site of the Heart Mountain incarceration Camp where many of the items in the Eaton collection were obtained — gathered pledges to make a cash offer of $50,000 to Rago Auction House. Bafflingly, that offer was turned down.

It seemed that Friday’s auction would go on as planned until on Wednesday, HMWF notified Rago of their intention to file a lawsuit challenging the legality of the sale, and actor George Takei also independently intervened. By Wednesday evening, Rago announced that the auction of the Eaton collection had been cancelled, and that a resolution would instead be negotiated with representatives of the Japanese American community (including Mr. Takei).

Throughout the unfolding of this story, one thing has remained unknown: the identity of the Eaton Collection’s consigner. Friday evening, the New York Times revealed that the seller is John Ryan, a sales and marketing employee for a credit card company, who lives in Connecticut.

Ryan took a phone interview with the Times to explain his side of the story.

“We have tried to be good stewards of this material and protect it over the years,” Mr. Ryan said in a telephone interview. “We weren’t trying to extort money from anyone.” He said that the auction house had assured him and his family that the likely bidders at the auction — where the top estimate for the materials was $27,900 — would be museums and other institutions that would be the best homes for such artifacts. And he added that the family wanted to sell the things, rather than donate them, because a family member in financial difficulty needed help.

“We really believed that it would be institutions that would step up and collect these materials,” he said. “We’ve always loved the collection.”

Ryan claims in the interview that he was motivated to put the Eaton Collection up for sale because of the financial needs of his family member. He also said he was moved by a philanthropic desire to ensure that the collection fell into the right hands.

I am unswayed by this claim.

Earlier this week, Ryan rejected HMWF’s cash offer for the Eaton Collection, which represented twice the collection’s estimated monetary value. On this decision, Ryan says:

“We didn’t feel qualified to make the decision about whether it should go there,” Mr. Ryan said, adding that the family had been assured by the auction house that several institutions would be present to bid at the sale.

That literally makes zero sense.

Ryan says he didn’t feel qualified to decide if HMWF was the appropriate recipient for the collection, despite the fact that the organization runs an educational center that preserves the legacy of Japanese American incarceration on the site of a former camp. But, let’s say we believe Ryan’s skepticism of HMWF’s offer and its intentions: how is an auction a better mechanism for identifying the most deserving recipient institution?

An auction does not identify the most deserving of museums and institutions to receive this collection of historic artifacts. An auction — by definition — identifies the museum and institution with the most money to spend to buy the collection.

The only reason to go ahead with an auction after receiving a cash offer double the estimated value of the items you’ve put up for sale is not because you doubt the integrity of the proposed purchaser; it is because you hope to make even more money at auction.

It is therefore impossible to reconcile Ryan’s stated motivations with his actions.

Meanwhile, Ryan does not address his earlier statement that the backlash from the Japanese American community to the sale amounted to “bullying”.

Ryan was named in Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation’s threatened lawsuit along with Rago Arts and Auction House, and its owner David Rago, which challenged the legitimacy of the sale. The Times reports that Ryan came to own the Eaton collection after he inherited it from his father, Thomas Ryan, whom the Times says received the collection after Eaton’s daughter, Martha Eaton died.

Thomas Ryan was a contractor who did some home repairs on Martha Eaton’s home after a house fire. While she was alive, she sold some of the collection to Ryan; he took ownership of the rest in 1990 after she died and he served as the executor of her estate. Soon after her death, Eaton friends and family members took Ryan to court in Westchester County to dispute Ryan’s claim to the Eaton estate, claiming that Ryan had taken advantage of her while Martha Eaton was “a delicate and fragile elderly woman, living alone” and who “was losing her physical and mental capacities”. A judge dismissed the suit citing a lack of evidence, and eventually the case was settled outside of court.

Nonetheless, this legal paper trail raises questions about the legality of Ryan’s ownership of the Eaton collection, and therefore of the Rago sale, itself.

But, perhaps the most distressing aspect of this entire fiasco has been its attempt to place a monetary value — whether $27,000 as Rago estimated, or $50,000 as offered by HMWF — on the few remaining mementos of incarceration camp life.

Sean Miura (@seanmiura) of Down Like JTown wrote evocatively of the value of these artifacts earlier this week. In his powerful blog post, Sean discusses how the forcible displacement of Japanese Americans left a generation of families with few physical memory objects of their past.

On a first look level, it’s obviously historically problematic. In case you don’t want to read the encyclopedia I wrote a couple months back, in 1942 120,000 folks of Japanese ancestry up and down the West Coast (citizens and immigrants who were not legally allowed to naturalize because racism) were put in concentration camps due to racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and failure of political leadership. In those camps, prisoners saw their families split up, illness run rampant, and shame seed itself in the hearts and minds of an entire generations, leading to decades of mental and emotional scars. For many, art provided a way to negotiate the horrible situation, and so art became part of camp culture. There were beautiful gardens at Manzanar built by the ingenuity of our working-glass gardener community, photos taken with contraband cameras, and tiny detailed birds that became a culture in their own. Mothers traded senninbari, a sash or vest with 1000 stitches in them, to send good luck, protection, and love with their sons when they headed to fight for the very country that imprisoned them.

Pre-war our families were largely in poverty, but what little we had was mostly lost once World War II began. Most of our families do not have boxes and boxes of heirlooms, meaning that any artifacts from that era are precious. For someone to accept donations and then presumably change ownership of the collection post-mortem means that somewhere along the line there was a dip in communication.

…It just feels disgusting. I am reminded of one of my favorite pieces of writing by Cara Van Le about experiences with commodification/trivialization of the Vietnam War (Part of Memory is Forgetting). In the piece, Le offers flashes of memory with little analysis, instead allowing us to consider these moments and attempt to articulate the gut response they evoke. What set this on fire so quickly, I think, is the gut-level feeling of disgust that comes when your history is being held and exploited in the hands of someone who does not have that personal context. It’s the realization that our bid for self-determination for decades has resulted in educational and economic attainment but little-to-no education for the people around us. It’s the reminder that people will do callous, awful things and while we have amassed allies, ultimately we will always need to advocate for our own familial, community, and personal health.

I refuse to hold our community accountable for this. This is not our mess to clean up. If things start to get shaky, we cannot segment ourselves over it. I applaud and thank “Uncle George” for stepping in, but I hope we can recognize that by putting a dollar value on our histories the seller has claimed responsibility for these items. If they consider the case of Mary Berg’s possessions, there is precedent for them to consider and act accordingly. It is up to them to work with our institutions, families, and public to determine how these items should be disseminated, with or without a price tag. To not involve the families and community that produced the items would be irresponsible. To sell them anonymously after acquiring them as donations for an articulated purpose would be immoral.

Poet Janice Mirkitani remarked after discovering a photograph of her cousin among the Eaton Collection, “These are pieces of art created in camps against our will. They are pieces of our soul.”

How much does a piece of one’s soul cost?