You can tell how unplugged I am from the mainstream fandom that the internet broke this week over a variant Batgirl cover, and I had no idea whatsoever.

Earlier in the week, DC Comics received a deluge of critical responses to a variant cover for Batgirl #41 drawn by artist Rafael Albuquerque. As my friend Will West points out in his blog post weighing in on the controversy, variant covers are special versions of a comic featuring unique cover art, and usually offered as an incentive to comic book stores to increase their orders of certain issues, with the idea that the increased order size cost can be recouped when the variant is sold as a specialty or collector’s item. Lately, both DC and Marvel have been issuing month-long variant cover themes, which invite artists to create art across a common focus that can span all issues; June’s theme for DC centers around the Batman villain, Joker.

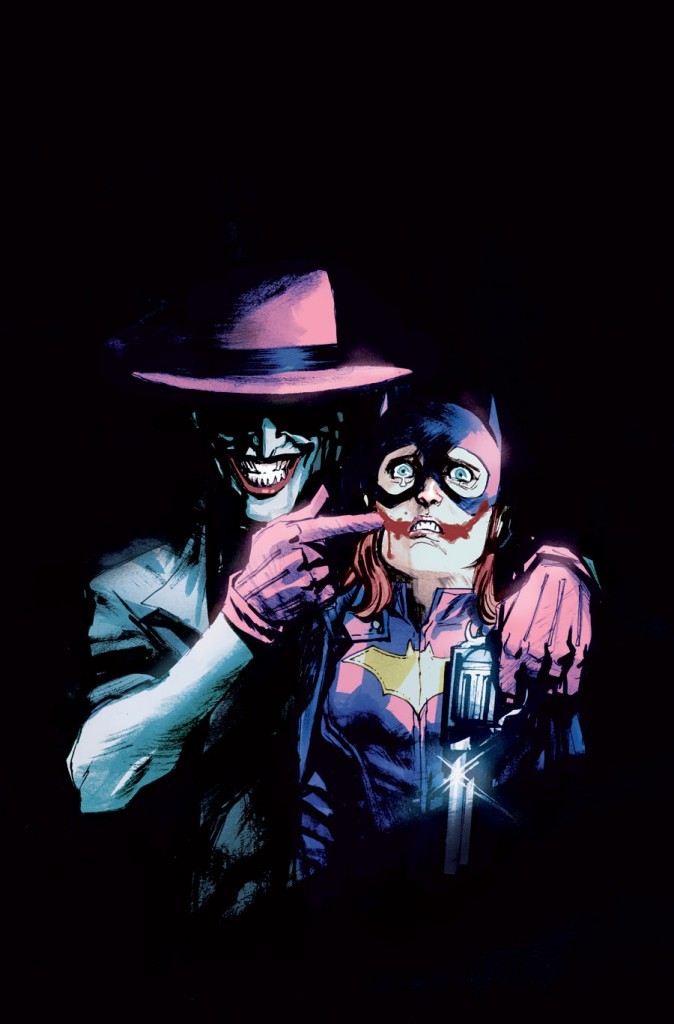

In this particular case, Batgirl #41‘s variant cover featured cover art depicting the comic’s heroine being terrifyingly brutalized by the Joker in an homage to a classic graphic novel (The Killing Joke) where he violently sexual assaults her and paralyses her with a gunshot wound.

Albuquerque’s variant cover for Batgirl #41 appears after the jump.

Many fans were outraged by this cover, and took to Twitter to express their anger. Eventually, a Twitter campaign — #CancelTheCover — was launched. This provoked backlash from other fans, ultimately leading to (as seems to be inevitable these days) death threats being lobbed against those who expressed objection and criticism to the cover.

I, too, find this cover outrageous.

Fans who support the variant cover (or, at least, the “right” for fanboys to purchase such a variant) have pointed out that the Joker’s relationship with Batgirl is deeply significant, and fraught with violence. My friend Will writes:

I think the Batgirl cover’s uncomfortable, but I also think that’s *the point*. There’s more storytelling in that image than anything current Batman writer Scott Snyder’s done.

To Albuquerque’s credit, the image is as striking and evocative as it is deeply derivative of the violent climax of Alan Moore’s landmark Killing Joke. Killing Joke is a fascinating and necessary character study of one of DC’s most complex and popular male villains; it is simultaneously a textbook fridging of a female superhero in order to accomplish this. Fans have long speculated that, in addition to being paralysed (presumably for life, except that nothing in comics is permanent), Barbara Gordon is raped in a climatic scene where Joker reveals naked pictures of her mid-trauma to her father (head over to Will’s blog for a scan of this page). Barbara Gordon is figuratively destroyed so that Joker can terrorize her father: there is no more classic an example of “women in refrigerators” than this.

Will argues that the violence of this scene — and therefore its relevance to the Batgirl #41 variant cover — is mitigated by the obliqueness of the rape, which is only contextually implied rather than overtly stated. Thus, asks fans, is Batgirl #41 really a glorification of sexual assault if she wasn’t really raped?

You bet. Regardless of whether Killing Joke depicts penetrative sex between Joker and Barbara Gordon or not, it absolutely depicts an example of violent sexual assault. After shooting her (itself a horrific and violent physical violation of Barbara’s body), Joker strips her naked, and photographs her against her will.

That is sexual assault. Period.

Fans are correct that this moment in the Killing Joke is a pivotal event in Barbara Gordon’s vigilante trajectory. She spends the comic book equivalent of years (and in actual time, over a decade of comic writing) recovering from this trauma while rebuilding herself as Oracle. Fans are incorrect in arguing that this important relationship between Joker and Batgirl justifies cover art that glorifies this violent, degrading, and arguably misogynistic moment of metaphorical (and possibly actual) rape and powerlessness of a superheroine being splashed across the cover of her own comic book title.

To their credit, DC Comics has not shied away from the topic of rape and sexual assault, although they have rarely treated it as much more than a plot device for the advancement of storyarcs featuring male heroes. However, in the years following Batgirl’s assault by Joker, Batgirl’s writers have slowly built a nuanced (and sometimes deeply painful) portrait of a rape survivor. To those who emphasize the importance of the events of Killing Joke to Batgirl’s history, I say this: my dear fans, you have missed the point.

Batgirl’s (metaphorical or actual) rape by Joker is not the critical piece to understanding Batgirl’s personal evolution as a hero; its aftermath is. A context-less, ham-fisted, and derivative graphical reminder of Batgirl’s sexual trauma, forced powerlessness, and victimization is neither high art, nor central to understanding who Batgirl is; it’s exploitative torture porn.

Earlier this week, DC decided to pull the Batgirl #41 variant cover after fans expressing criticism of the cover documented that they were receiving online death threats for their opinions (because threatening feminists with violence has become the go-to harassment tactic in geek culture, apparently). In addition, artist Rafael Albuquerque expressed personal regret for the image. In a statement, he said:

“My intention was never to hurt or upset anyone through my art… For that reason, I have recommended to DC that the variant cover be pulled.”

Predictably, a new wave of anger was triggered by this decision, with fans now claiming censorship.

I don’t support terrorism-fueled censorship. But, this is not censorship.

Censorship would be launching a DOS attack against DC Comics’ website until they agreed to pull the cover. Censorship would be looting comic book stores that sell the Batgirl #41 variant next to its standard shipped cover. Censorship would be a mass book burning. Censorship would be sending death threats against people you disagree with to scare them into silence.

Censorship is not expressing a critical opinion as a comic book consumer about a product you might otherwise purchase. Censorship is not notifying the maker of your favourite comic book that you think they have misstepped, and asking them to reconsider. Censorship is not that comic book studio — and even the comic book artist in question — agreeing, and voluntarily pulling the offending comic book cover. You, dear fan, are not being censored because DC Comics has voluntarily decided they are no longer going to sell you something; and more specifically, something that another population of consumers have expressed serious offense towards.

Put more simply: dear fan, are you saying that our consumer interests are simply less important than yours?

Will asks, somewhat facetiously:

What bothers me is the precedent that this sets…. Are they going to have to run everything by The Mary Sue (popular website by and for female comic fans) before they approve it? Does Gail Simone (DC Comics’ most prominent female writer) have to give her approval for everything concerning women before it’s universally accepted by fans? Are all controversial comic decisions going to have to be approved by some sort of committee comprised of fans and professionals?

But I counter with this: forgetting the obvious hyperbole in this quote (no one is asking that Mary Sue editors get DC Comics veto power), is it really such an imposition for the comic book industry to start to think about the diversity of the comic book audience? The problem here was DC’s presumption that all comic book fans are the “conventional” comic book fan: White, male, and titillated by adolescent references to sexual violence. The problem here was DC’s failure to recognize that today’s comic book audience encompasses fans who don’t fit this stereotypical trope; we are women, people of colour, and some of us don’t care much for glorifications of sexual violence and implied rape in the comics we buy.

Comic book writers and artists aren’t creating comic books in a consumer vacuum; they create comics to sell to fans. Catering to fan interests is what they do, and what they have done for a century. There’s nothing revolutionary about saying: it’s 2015, and therefore time for creators to start thinking about more than just what will appeal to one kind of fan.

Meanwhile, Snoopy Jenkins makes the most important point I’ve read to-date about the Batgirl variant cover controversy: this isn’t just about glorification of sexual violence, but also about mainstream comics’ and fans’ resistance towards contrasting feminist depictions of superheroes. This isn’t just about a variant cover with a terrified Batgirl ensnared by a predatory Joker, but about a nerd community that fights (with death threats) to keep this image on comic book shelves while it fights (with death threats) to silence the work and opinion of feminist content creators and fans who offer an alternative portrait of female heroics. Snoopy writes as a comment to Will:

[I]n comics, men tend to identify with a free speech coarse enough to support depictions of violence against women for profit, but too fragile to support actual feminist characters that do more than sad aggro imitations of male superheroes.

Put another way, I’m all about allowing whatever variant covers in comics that are supported by the market, but I find little redeeming value in this art, and question why DC and Marvel artists can always find room for sexual violence against women or hypersexual women, but never find room for respectable feminist characterizations of women. Incidents like this illustrate how distant the mainstream comic publishers and their overwhelmingly male audience are from the modern feminism female comic fans fail to inject into the industry.

Asking the Mary Sue for feminist approval, however tongue-in-cheek, is precisely not the point. DC can tell decent stories with or without sadomasochism and female torture, but if they wish to use that stuff someone should at least interrogate why it appeals to the audience, and why they can’t also sell meaningful feminist material as well. An audience that will purchase terrified Barbara Gordon or apple-bottomed Spider-Woman but shuns feminism is an immoral and sexist audience. Capitalism and free speech ideals can’t defend that.

Mic drop.

***

Addendum: either way, I still wish they’d bring back Cassie Cain’s Batgirl.