Most of us also know the name of Chelsea Manning, who prior to taking her new identity as Chelsea served as Bradley Manning in the US Army where she leaked the largest package of classified information to the public via Wikileaks, including documents pertaining to US airstrikes in Iraq and Afghanistan. Manning was prosecuted under the Espionage Act and is currently serving 35 years in prison.

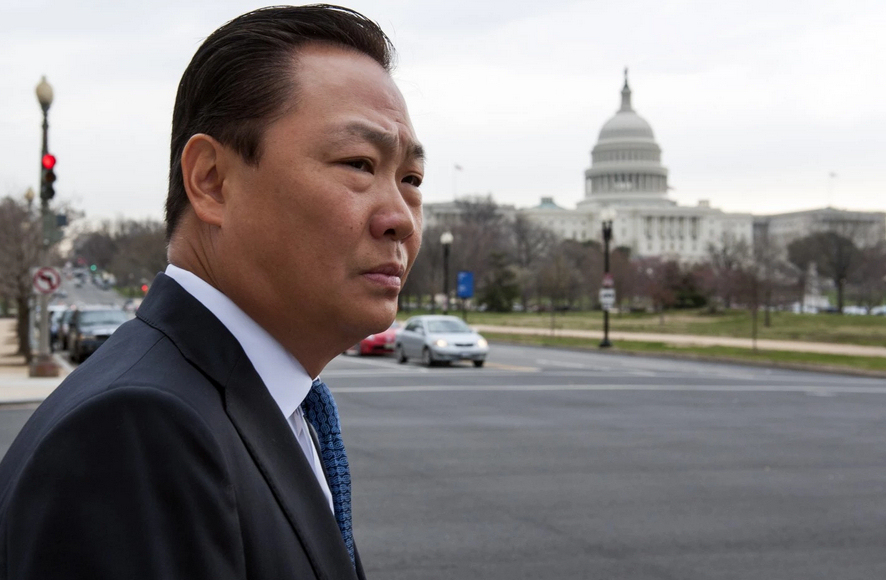

Few of us know the name of Stephen Jin-Woo Kim, a Korean American former mid-level contracted analyst who worked in the Pentagon’s prestigious Office of Net Assessment think-tank and then later in the State Department’s Bureau of Verification, Compliance and Implementation. In 2010, Kim became one of a handful of analysts and journalists targeted by the FBI; these investigations were a manifestation of the Obama Administration’s sudden and unprecedented crackdown on internal leaks in the wake of the Manning case.

Prior to 2008, prosecutions under the 1917 Espionage Act — which ostensibly protects the country from military insubordination and aiding foreign enemies — have been relatively rare in modern history. Early in its history, the Act had previously been used in part to justify mass deportations and prosecutions during the Red Scare of 1918-1919; however, upon recognition of the base unconstitutionality of this practice, many of those prosecuted were pardoned by President Woodrow Wilson in 1919-1920 and the use of the Espionage Act as a tool for a state-sanctioned witch-hunt had been largely abandoned.

However, since President Obama took office in 2008, his administration has used the Espionage Act to pursue charges against Manning, Snowden, and six other journalists and State Department analysts. Pundits and historians unanimously agree with Jake Tapper’s succinct assessment: “The Obama administration has used the Espionage Act to go after whistleblowers who leaked to journalists … more than all previous administrations combined.”

Stephen Kim, born Jin-Woo Kim in Seoul, South Korea, immigrated to New York with his family when he was only 9 years old. Kim earned his undergraduate degree at Harvard in national security, and his PhD from Yale in diplomatic and military history. Kim specialized in nuclear weapons programs and nuclear proliferation; he also spoke fluent Korean and was both familiar with — and impassioned over — American policies towards North Korea.

When North Korea made several public tests of their budding nuclear capacity beginning in 2006, Kim and his uniquely intersectional expertise was a natural choice to advise the government. At one point, he was even sent to Washington to brief Vice President Dick Cheney.

Kim’s politics and personal background also predisposed him to a hawkish outlook on North Korea, which The Intercept reports frequently left Kim frustrated with what he perceived to be America’s moderate outlook and toothless sanctions towards North Korea. The Intercept’s Peter Maas notes that there is an informal, if commonly understood, culture by which analysts might pressure the government via the news media. Writes Maas (emphasis added):

There is a time-honored way in government for mid-level experts to convey their worries that high-level officials are misguided — they talk to reporters to raise an alarm outside the walls of whichever department they work for. This is why confidential conversations in Washington seem to take place in parks and restaurants and store aisles as much as they do in actual offices. These conversations can serve as a check on the official statements that portray prevailing policies as wise and successful, even when they are not.

It is this culture of interaction between analysts and reporters that the Obama Administration has quietly been cracking down on, using the Espionage Act with new and largely unprecedented frequency.

In 2009, frustrated by the Obama administration’s unwillingness to take a hard-line militaristic stance on North Korea, Kim was connected by a colleague — VCI public affairs head John Herzberg — to Fox News reporter James Rosen. In a series of emails, Rosen appears to pressure Kim to disclose classified information and leak other State secrets (which, incidentally, is a prosecutable offense, as we learned in the final season of Aaron Sorkin’s Newsroom). Although Kim took several phone calls with Rosen and appeared interested in working with the reporter to encourage a tougher American stance on North Korea, Kim does not ever explicitly respond to those requests. In fact, to date, there has been no direct evidence that Stephen Kim ever handed over any classified information to James Rosen.

Despite this lack of evidence, Kim was charged in 2010 with espionage, as well as lying to FBI. The charges pertain to an exchange between Kim and Rosen on June 11, 2009. This was just a few weeks after North Korea’s second nuclear test, and its first successful one. In the wake of the test, the United Nations was positioning itself to condemn North Korea. Rosen contacted Kim by phone, and over the course of the day, both left the State Department twice at roughly the same time indicating they may have met in a public place. That day, Kim was also a handful of people with access to a classified memo on the North Korean nuclear test, and internal records show Kim downloaded it that day, between his meetings with Rosen. Shortly after the second alleged meeting, Rosen published an article on the Fox News website under the headline “North Korea intends to match UN resolution with new nuclear test“, which describes the intelligence community’s latest assessment of the North Korea situation.

The Justice Department contends that Rosen wrote the article in part after obtaining the classified memo from Kim in the second meeting.

Yet, to reiterate, to date there is no evidence that Kim ever actually handed any classified information to Rosen. In fact, several journalists have noted that Rosen’s article is lacklustre; Maas says that Rosen’s article did little more than summarize the “conventional wisdom of the day”.

Over the subsequent several months, it slowly became clear to Kim that the Justice Department was actively pursuing an espionage case against him, even though Kim’s attorneys have outlined the lack of evidence against him and have further demonstrated that Rosen was in touch with several analysts with access to that classified North Korea memo on that day in June of 2009 — including Kim’s colleague, John Herzberg, who first introduced Kim to Rosen. Any number of them could have leaked the memo to Rosen, say Kim’s lawyers.

Yet, the FBI focused their attention on Stephen Kim. Could Kim’s race have been a factor — if implicitly — in the decision to pursue the case? Kim contends that during a search of his home, one of the FBI agents made provocative statements about Kim and all Asian Americans. Reports Maas:

One of the agents, apparently frustrated that they weren’t discovering anything, used a phrase that Kim interpreted as a racial slur, referring to him and other Asian-Americans as “you people.” (The government denied this exchange took place.)

While Stephen Kim is the only one of the 8 journalists and analysts prosecuted by the Obama administration under the Espionage Act to be Asian American, there’s also evidence to suggest that implicit anti-Asian bias colours (pun intended) life in the intelligence community for many Asian Americans. I’ve previously reported about the culture of suspicion and outright hostility many Asian American and Muslim analysts — recruited for the bilingual status — face at the State Department grounded in the implicit stereotype of disloyalty that has resulted in an informal blacklisting of these agents based predominantly on their race. Meanwhile, open race-based suspicion of Wen Ho Lee, an accomplished nuclear scientist, led to the government filing charges of espionage against the Taiwanese American in 1999, alleging that he had given State secrets to the Chinese government; those charges were later dropped due to lack of evidence.

This history makes clear a pattern by the State and the Justice Departments of a culture of Asian American mistreatment characterized by a heightened perception of Asian Americans as foreign, suspicious, and inscrutable, whether the evidence supports such contentions or not. This is, as Snoopy has argued to me in the past, one of the most compelling contemporary examples of institutionalized anti-Asian racism in America.

We know the names of Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning; yet we know their names in part because we have evidence of their broad and deliberate leaks of classified information as a form of whistleblowing. There has been virtually no press focused on the six other men who have faces espionage charges under the Espionage Act: almost all have been charged in cases with little or no direct evidence of deliberate espionage in arguably disproportionate uses of the law to punish relatively minor infractions or cases of mistaken disclosures. Do we not know Stephen Kim’s name because he is Asian American, and therefore the narrative of the untrustworthy spy fits more readily with our implicit biases? Or, do we care more about defending the righteous whistleblower than we care about miscarriages of justice that are quietly leading to aggressive convictions of the innocent?

After five years of attempting to defend himself against the Justice Department’s charges of espionage, Kim has lost his job, his marriage, and anything else that has made him feel human. He recounts to The Intercept how he has contemplated suicide. By 2014, facing near-bankruptcy related to his legal fees, Kim decided to accept a plea deal: a deal that, by no means, is an admission of guilt. Kim was sentenced to a 13-month prison term, which he is currently serving in Cumberland Camp, a medium-security facility in upstate Maryland.

From the moment he arrived in New York City as Jin-Woo Kim, he had set to work on constructing a new self, becoming Stephen J. Kim, a successful immigrant with Ivy League degrees who advised the White House and was privy to some of the nation’s most sensitive secrets. Now, he told me, he had to deconstruct that identity.

“My reputation is gone,” he said over dinner at a Japanese restaurant in Reston. “I don’t have any power. I am not a human being. I am the property of the state.”

He picked up a plate and held it aloft. “I am like this,” he said. “I don’t have rights. There’s no Stephen Kim. It’s erased. I am prisoner number whatever.”

Today, Stephen Kim is one of the approximately 1200 prisoners currently incarcerated at Cumberland. He is prisoner number 33315-016.

Read More: Destroyed by the Espionage Act (The Intercept)