If you follow AAPI blogs, you are aware of the latest great big ripple in our little pond. If not, here’s what’s going on: two major icons of Asian America have (kind of) declared war. Over the weekend, Lela Lee — creator of the comic strip Angry Little Asian Girl and subsequent merchandising — wrote a post outlining an ongoing trademark dispute between herself and Phil Yu, blogger of Angry Asian Man.

Lee contends in her post that Yu and his online moniker infringes upon the registered ALAG trademark, and that the similarity between the two names will create consumer confusion: basically that the casual reader might mistake Angry Little Asian Girl and Angry Asian Man as related products originating from the same person. Lee goes on to accuse Yu of having plagiarized much of Angry Asian Man from the Angry Little Asian Girl business model — she cites his Angry Reader of the Week feature and a t-shirt design — and of basically taking credit for the phrase and concept of the “Angry Asian”.

Yu responded with his own blog post yesterday, unique in that it is probably 10 times longer than anything Yu has ever written for his site. Yu discloses in his post that not only has this dispute been ongoing for the better part of the last year, but that Lee has sent Cease & Desist letters to both himself and Wendy Xu, creator of the web-comic Angry Girl Comics, threatening both with additional legal action. Xu has since also published her own side of the story, confirming that she has also been targeted by Lee’s lawyers.

So, this is a thing happening right now in Asian America; so, let’s talk about it.

Disclosures

Let’s make one thing clear: I’ve been blogging for a long time — long enough to have basically been around to know how both Yu and Lee arrived on the scene. I don’t really need to rely on either Lee‘s or Yu‘s account of what Asian America was like a decade ago; I remember.

Let’s make another thing clear: I’m not “friends” with Phil Yu or with Lela Lee. I’ve met Phil once, over ten years ago, when we sat on a panel for ITASA together and then had dinner afterwards. I since have emailed and messaged him a couple of times, mostly to put things on his radar for Angry Asian Man. Phil is a really nice guy (and no, he’s really not that angry) and a staunch Asian American activist. I make a monthly $2 contribution to his site out of respect for its importance to the online Asian American community. Phil and I have a cordial, collegial relationship, but we do not know each other personally. We don’t text or do lunch or have coffee. I would have no trouble not being on #TeamPhil if I think he’s wrong on something.

I’ve never met Lela Lee but have interacted with her one time through direct messaging when she thanked me for writing a feature regarding Angry Little Asian Girl when the character turned 20 years old last year.

Let’s make one last thing clear: I respect both Phil Yu and Lela Lee immensely, and this is perhaps why this Angry Asian conflict has impacted me and so many others. Like so many other Asian American bloggers of my generation, both Angry Asian Man and Angry Little Asian Girl were formative in inciting us towards social consciousness. In my 12-year anniversary post, I wrote about how the existence of Angry Asian Man served as an inspiration for this site. In my feature for Angry Little Asian Girls, I wrote about how I identified so strongly with Lee’s ALAG character that for the first several years of this blog’s existence, I subtitled it “ramblings of an angry little asian girl”. An ALAG sticker was posted prominently on the desktop computer that I used to design and upload the first iteration of this site. If Phil Yu is the Superman of Asian America, Lela Lee is the Wonder Woman.

I’m writing this post to clear up where I stand on the Angry Asian conflict. The take-home message is this: I think Lela Lee is wrong, but importantly I don’t arrive at that conclusion because I want to defend Phil Yu for some special reason. I have mad (and largely equal) respect for both parties involved. I arrive at my conclusion because I think, on the merits, Lela Lee is actually wrong.

The Case

This section is a lengthy discussion of the case itself for (or against) trademark infringement. If you don’t care, you can skip it.

As might be expected by regular readers of this blog, I’ve spent the last 24 hours reading up on copyright law and trademark infringement in preparation for this post. Here’s the basic skinny: a registered trademark offers the owner of the trademark certain exclusive rights to the trademark that, among other things, allow for the owner to protect the trademark from infringement. What constitutes trademark infringement can take on several forms, but the basic point is to prevent consumer confusion; that is, whether or not a consumer might mistake two unrelated brands. While many have spoken out on social media declaring that they would never confuse Angry Little Asian Girl and Angry Asian Man, the test for consumer confusion has very little to do with polling actual consumers; there is an informal legal standard used by the courts (called the “Lapp test”) that guides the determination of whether two brands might be confusing to consumers.

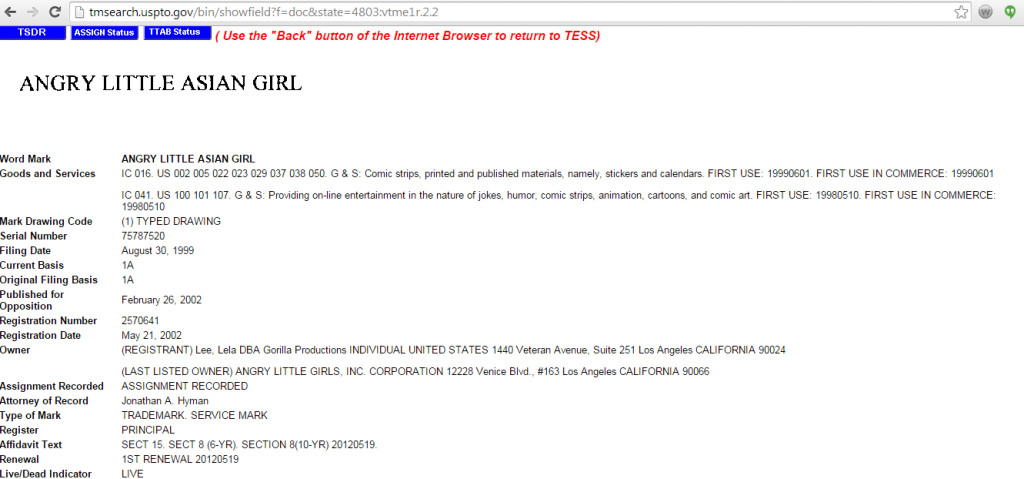

Some factors of the Lapp test might show that Lee and Yu’s brands are strongly overlapping, however, two important factors are related to how much both brands are performing the same function for a similar market; here’s where things actually get dicey. Lee registered her first trademark in 1998 for Angry Little Asian Girl for a cartoon or comic strip with an additional trademark registered in the same year for T-shirt sales; both were subsequently abandoned within the year. In 1999, Lee re-registered Angry Little Asian Girl as a goods and services trademark. She specifies in her application that the goods she will sell are “comic strips, printed and published materials, namely, stickers and calendars”; her services are “providing on-line entertainment in the nature of jokes, humor, comic strips, animation, cartoons, and comic art”. This is the registered trademark that has endured for the last decade, and would be the relevant trademark application that would have applied to the time when Yu launched Angry Asian Man in February of 2001. Nowhere does she talk about Angry Little Asian Girl applying to blogging, television shows, or — importantly — social or political commentary.

Lee renewed the Angry Little Asian Girl trademark in 2012. At that point, she filed an “intent to use” application (and then subsequently demonstrated actual use) which expanded her use of the trademark to encompass television programs and web videos that might tackle, among other things, “social issues”.

The take-home message here is that Lela Lee has held a trademark over the phrase “Angry Little Asian Girl” since 1999, but that for most of this time, the trademark focused on a product described in the application as a humour comic; even with Lee’s 2012 renewal, her application focuses on television programs and web comic videos. In fact, Angry Little Asian Girls (and its offshoot Angry Little Girls) has always had a fairly minimal blog-type presence. Meanwhile, Angry Asian Man is a blog that focuses on Asian American politics and pop culture and occasionally he has sold some t-shirts. As far as the US Patent Office is concerned, the two brands reference two distinct products, and this is an important consideration when thinking about the basis for trademark infringement and the likelihood of consumer confusion.

This is why in her post, Lee also focuses on the question of trademark dilution — that is, protections to a trademark’s senior user from loss of uniqueness due to two people using similar logos or brand marks to refer to two distinct types of products: in doing so, Lee acknowledges that Angry Asian Man and Angry Little Asian Girl are performing dissimilar functions. But, the problem with invoking trademark dilution is two-fold: 1) it generally requires that the brand be “famous” (which has its own legal standard) and 2) whether the brand is diluted by either “blurring” or “tarnishment”. Tarnishment refers to the harm caused to brand by having a similar mark referring to a product that actually hurts its reputation, so for example, Toys ‘R Us wanting to maintain a child-friendly brand filed a suit against Adults ‘R Us, a porn website, on the basis of tarnishment. Since this basically doesn’t apply to the Angry Asian conflict, we can assume that Lee is invoking trademark dilution under the basis of “blurring”; or, in other words, that there can be only one “Angry Asian”. We’ll revisit that in a second.

Yu counters in his blog post that Lee has basically taken too long to file action against him: he has, after all, been blogging under the Angry Asian Man moniker for 14 years this weekend and was only hit with his Cease & Desist letter last year. Yu is invoking what is called the Laches Defense; the idea being that it’s unfair for someone to register a trademark, wait for a competitor to invest resources to build up the popularity of a brand, then swoop in and take everything. This article notes that delays greater than 3-4 years are typically sufficient to invoke laches, and that only in a handful of outlier cases did laches fail to protect a defendant after a 13 year delay. I agree with Yu: waiting 14 years — or at least 9 years, if one believes that Lee was unaware of Angry Asian Man until 2005 — is simply too long to pursue enforcement of a trademark.

Lee argues that the delay was related to progressive encroachment, another technical legal term. Basically, the Laches Defense can be countered if the trademark holder can demonstrate that a case for trademark infringement couldn’t be made until the competitor started wandering into the market of the trademark holder, which would explain the delay. In her post, Lee argues that Yu’s decision to blog full-time was evidence of progressive encroachment — that he didn’t encroach until he started taking his blog more seriously. That’s a pretty suspect argument, since progressive encroachment must be demonstrated in material changes to the market (i.e. a substantial change in product that shifts the focus of the products so that they now overlap) and not just because more man-hours have been invested.

So, for example, progressive encroachment might be if Yu decided to start a web comic called “Angry Asian Man”. It’s harder to see how progressive encroachment is occurring simply through Yu being a better blogger because he’s now doing it full-time. Materially, the market has not changed.

A better argument might be that Yu engaged in progressive encroachment when he decided to start making television programs under the Angry Asian Man brand; remember that Lee expanded her trademark in 2012 to include TV programs. There’s a couple of problems with this though: 1) the TV program aspect of the Angry Little Asian Girl was first outlined in 2012 and didn’t come under protection until 2013, and 2) the application to expand the Angry Little Asian Girl away from humour comics into the territory of social issues actually represents action by Lela Lee to bring her comic closer to the Angry Asian Man wheelhouse. As the International Trademark Association writes (emphasis added):

In order for the senior user to invoke the progressive encroachment doctrine, the junior user must have taken some action that materially alters the present situation in the marketplace. However, if the senior user’s conduct brings the two parties into closer competition, the progressive encroachment doctrine does not apply [except under certain circumstances related to jurisdiction irrelevant to this case].

While there’s some argument in favour of Lee’s encroachment argument with regards to the TV program format, Lee’s expansion towards commenting explicitly on “social issues” (rather than her previously outlined focus on humour comics) represents conduct that brings her brand in closer competition with Yu’s Angry Asian Man, which has been commenting on social issues since the blog’s founding.

Yu also outlines how for most of his time as a blogger, he has had a congenial relationship with Lee that suggested that she was both aware of his moniker and, important for this case, was largely okay with his use of it, such as the panel discussion she organized that included both as “Angry Asian” guests. The International Trademark Association has this to say on that (emphasis added):

…[A]cquiescence… is not based on the passage of time but is instead generally signaled by some type of assent by the senior user to the use of the junior mark, coupled with reliance on those assurances by the junior user to its prejudice. Such assent may be express (active affirmative consent: “I do not object to your use of XYZ mark”) or implied by conduct (e.g., the senior user distributes its own products and those of the junior user to the same customers). In the context of either estoppel by laches or estoppel by acquiescence, “prejudice” means an injury to the junior user’s business and the goodwill it has already created in its mark resulting from the junior user’s reasonable reliance upon a justifiable expectation that the senior user would take no action against the potential infringement.

Basically, you can’t signal by your actions that you’re cool with someone infringing on your trademark for a bunch of years, let them build up their brand that becomes their livelihood, and then pull a switch saying you were never okay with it to begin with and now it’s time to hand all that success over.

There’s a few other nitty-gritty issues I want to mention. In Lee’s post, she goes on to accuse Yu of plagiarism. She cites three examples: 1) a screen capture of her website used in a talk where Yu is praising Lee’s work; 2) Yu’s ongoing Angry Reader of the Week feature; and 3) a t-shirt design. These details suggest Lee may be unfamiliar with certain aspects of copyright law and what constitutes plagiarism. Use of a screen capture — and even her trademarked Angry Little Asian Girl brand — when in reference to her or her work constitutes nominative fair use and further was not even used in the context of commerce; trademark infringement simply does not apply. Second, Lee simply doesn’t have a patent on weekly reader profiles: not only is the example offered by Lee in her post hard to reconcile as similar to those published by Yu, but neither party are the first nor the last to feature readers in a profile format. Finally, Lee posts a picture of a 2005 t-shirt design she says Yu cribbed from her:

This was, incidentally, the strongest evidence in my mind that there might have been some plagiarism (intentional or otherwise) going on. I mean, a blue continental United States over some text about America? Come on.

That is, until Snoopy Jenkins peeked over my shoulder while I was reading Angry Asian Man‘s post and remarked, “uhh, isn’t that the Air America logo?”

You mean this one?

So who cribbed what from whom? If Lee is frustrated that Yu’s shirt is too similar to her 2005 design, what does she have to say about the similarities between her t-shirt design of 2005 and Air America’s logo of 2004?

Here’s what’s most likely: Yu didn’t copy from Lee. Both Yu and Lee drew from the same well-trafficked graphic design well — a map of the U.S., a sans-serifed font, and a oft-used shade of blue popular precisely because it’s pleasing to the eye and prints well (which is why it’s also the default blue for Microsoft Office products) — and accidentally ended up with very similar designs. It happens; as a graphic designer, I couldn’t say I wouldn’t have made a similar logo if tasked to design something for a thing called “Angry Asian America”. The similarities in the designs aren’t by themselves definitive evidence of malicious motive, particularly in the absence of additional evidence that Yu was deliberately plagiarizing Lee.

That being said, if I were Phil, I’d probably discontinue sales on that t-shirt; it’s really close to the Air America logo.

So in summary: trademark infringement and subsequent lawsuits are complicated. Lela Lee might have had a case against Phil Yu several years ago (a judge would’ve had to decide in regards to the Lapps test as to whether or not there was sufficient likelihood of consumer confusion), but having waited 14 years while also having moved her brand towards the type of service Yu has performed with his blog for years significantly weakens her case.

As for Lee’s actions against Wendy Xu, Lee holds trademark on Angry Girls Inc. as well as Angry Little Asian Girl. While Xu’s Angry Girl Comics might be apparently overlapping with Angry Little Asian Girl, it’s worth noting that the US Patent and Trademark Office apparently doesn’t view Lee’s trademark as barring other trademarks on the combination of “Angry” and “Girl” in a brand: there is currently also an active trademark on “Angry Workout Girl”, a clothing line and they permitted a now-inactive trademark on “Angry Gurl”, a brand with an Asian-inspired logo that sold stationary, during the time that Angry Girls Inc. trademark was also active. So I literally have no idea whether a judge would see Lee’s and Xu’s comics as confusing to consumers on the basis of their names.

So, yeah — in my humble opinion, on the merits of the case, Lela Lee is wrong.

There Can Be More Than One “Angry Asian”

Beyond the legal stuff, my entry point into the Angry Asian conflict is really more about its political ramifications to Asian America. Whether or not Angry Asian Man is a trademark infringement to Angry Little Asian Girl is ultimately up to a judge (and I am not one). Yes, Lela Lee has every right to pursue civil action against Phil Yu (and Wendy Xu), even if I think the case is too weak to hold up.

What saddens me is that two titans of Asian America have come to blows over who has exclusive rights to call themselves an “Angry Asian”. When Lela Lee invokes the “blurring” aspect of trademark dilution, that is, in essence what she argues: that she has exclusive rights to being known as the web’s only “Angry Asian” and that to have multiple people identifying as such harms her brand.

In an email to Yu, Lee writes: “You have no right to be known as the “Angry Asian.””

Why the definite article? Because by implication, Lee asserts that the right to refer to oneself as the “Angry Asian” is hers alone.

I’ve outlined why I don’t think Lee is right on her trademark fight, but more importantly, I do not think Lee has the moral right to claim ownership or origin of being an “Angry Asian”.

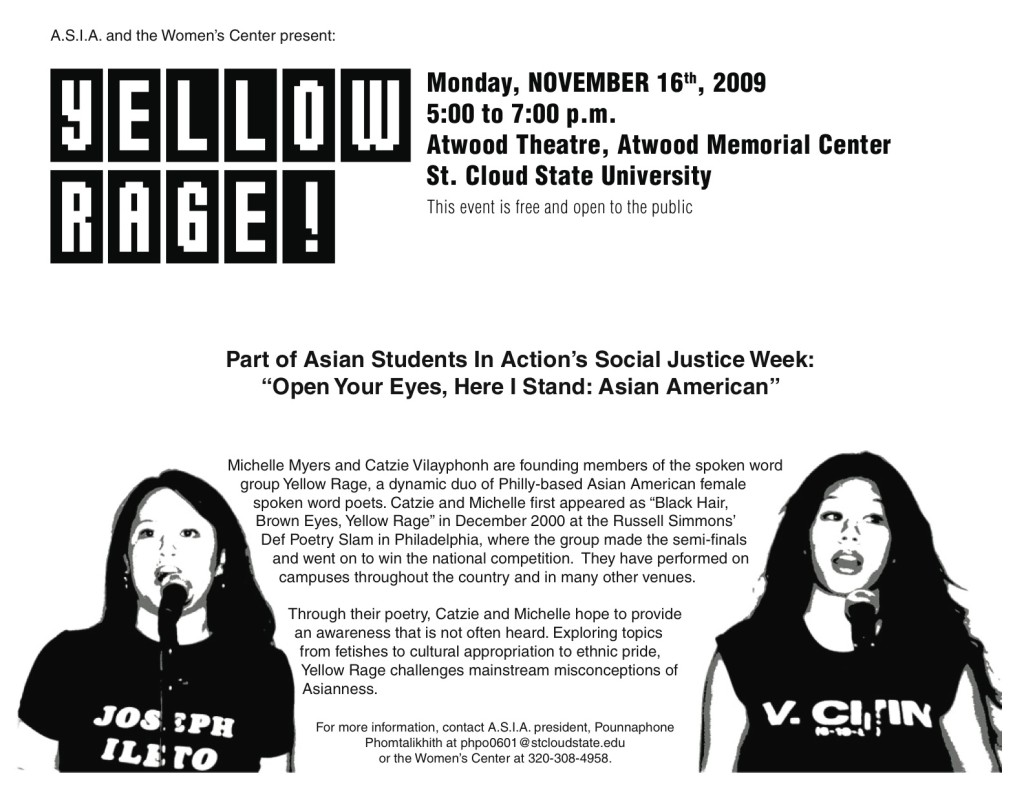

As I mentioned at the start of this post, I remember the time when both Yu and Lee arrived in the online Asian American scene. This was a time when words like “angry” and “mad” were a common short-form for a specific type of Asian American subversiveness. This was the Model Minority Mutiny of 15 years ago. As Yu notes in his post, the era was full of self-identified Angry Asians. There was a spoken word group called “Yellow Rage” with a piece called “Mad As Hell”. I Was Born With Two Tongues had a piece called “Excuse Me, Amerika” that also touched on being the “too angry” Asian. If you were active on forum boards or Asian Avenue in the early aughts, chances are you had more than your fair share of friends with a screen-name that included the words “angry” and “Asian” in some combination; maybe you did, yourself.

This is important historical context because the phrase “Angry Asian” is more than just a brand or trademark; it is an expression of sociopolitical revolution against anti-Asian stereotypes. It resonated for many Asian Americans, particularly those in my generation, as a call for social awakening against racial injustice. “Angry Asian” was a phrase that arose organically as an articulation of a more progressive racial politic.

As I grappled with the Angry Asian Conflict with Snoopy over the weekend, he reminded me that the biggest issue with Lee’s argument is that it — by definition — discourages today’s young Asian Americans from identifying as “Angry Asians”. Sure, Lee may not be arguing against social awakening, but she is denying access to the language of that social awakening. Asian Americans are being told they should no longer see themselves as “Angry”, or risk a lawsuit.

And, it has always been my bias that any action that arrives at the endpoint of discouraging young activists from growing their own activism is something I will always oppose. Period.

There cannot be just one “Angry Asian”. The internet must be big enough to have more than one “Angry Asian”. The whole point of the Movement is to inspire a generation of “Angry Asians”.

Above all, I am supremely disappointed by the aftermath of the Angry Asian Conflict, and specifically what it has revealed about a woman I have held as a personal feminist icon. Angry Little Asian Girl has been a particular inspiration for me because it helped articulate my own budding feminism.

To read Lee uphold heteronormative gender roles by admonishing Yu for not being his family’s primary breadwinner was disconcerting. What’s wrong with a woman earning more than her male spouse, or a blogger — many of whom are women of colour — working on a “donations” basis?

To find that Lee rejects the term “feminism” and even implies it is a slur of some kind was unspeakably heartbreaking.

https://twitter.com/LelaLee/status/567946696509886464

There are some who are defending Lee’s threatened lawsuit as evidence of a strong businesswoman protecting her trademark against the patriarchy, symbolized by Yu’s prominent role in the Asian American blogosphere. There are those who argue that this is yet more evidence of a woman of colour having her work erased by men. Lee herself has started to champion these defenses on Twitter.

Is the Asian American blogosphere frustratingly male-dominated? Absolutely. Could it use amplification of a broader range of voices, including feminist voices? You bet (and I’ll humbly advance my own as a candidate for more amplification). Is there something courageous about a woman challenging a male gatekeeper? Of course — but only when she is right on the merits. It’s feminist to support a woman when she has clear rhetorical ground to challenge a man in power because she is right and he is wrong; it’s not feminist to support a woman who hasn’t built a good case for herself just because she is a woman and you want to see a man taken down a peg or two.

Before I sat down to write this post, I was going to conclude this post with the line that my respect for both Lela Lee and Phil Yu has not diminished with this conflict, but that is no longer true. I was going to write that I hoped that the conflict could be taken out of the public eye and resolved privately in a mutually beneficial fashion. Now, however, I have to confess: my respect for Lela Lee has decreased. And, it has nothing to do with her decision to file action against Phil Yu, and everything to do with the Tweets and comments she has posted since publishing her post.

Let me be clear: we should all be pushing back against some of the language being used against Lee. Let’s avoid the kind of sexist stereotyping that would dismiss Lee as “bitter”. Let’s avoid the kind of ableist language that would dismiss her as “crazy”. That’s not helping anything.

In general, I’ve got nothing against members of our community disagreeing, even when that means taking a principled stand against those most prominent among us. I can commend a strong Asian American woman challenging an Asian American man in defense of her business interests, even if I can’t condone it because she’s on shaky legal ground.

But to have my feminist icon — the one who spurred me to the self-realization that there is nothing shameful about being a feminist — declare that being called feminist is a form of name-calling?

Disappointed doesn’t even begin to describe how I feel right now.

Read more:

- Angry Asian Man Is Being Threatened with an Angry Asian Lawsuit (Fascinasians)

- Angry Attacks (Kevin’s Blog)

- If You’re Not Angry, You’re Not Paying Attention (Scott Kurashige)

- A Battle of Angry Asian Trademarks (Simon Tam)

Update (2/19/2015): Please read this post for new developments on this topic.