More than three years after the untimely death of comics legend Dwayne McDuffie — the man who can be rightfully pointed to as the pioneer of today’s diversity efforts in mainstream comics — Washington Post is exclusively reporting that McDuffie’s Milestone Media may rise again.

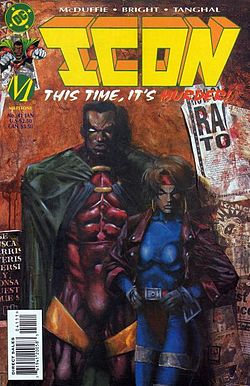

McDuffie, who died suddenly at the height of his career, is credited for co-founding Milestone Media, the parent company of Milestone Comics, in 1993 during a boom in the comic book industry. However, unlike other independent comic book studios started in the era (such as Top Cow and Image), Milestone was started with a very specific and political purpose: to promote a broader racial diversity within the comic book medium. Recruiting top minority writing and artist talent, launched with a slate of comic titles focused on minority superheroes, including Static and Icon which introduced characters Static Shock, Icon and Rocket; all are now characters in the DC Comics mainstream pantheon.

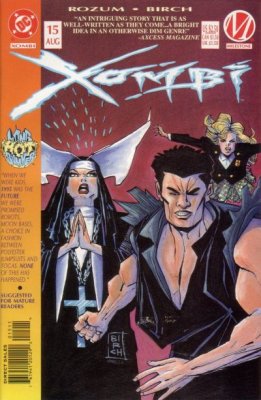

Although many of Milestone’s earliest characters were Black, Milestone supported efforts to bring all forms of racial and sexual diversity to comics, which included the introduction of several Asian American superheroes. In 1994, Milestone launched Xombi, written by John Rozum and illustrated by Denys Cowan. The title focused on Korean American hero David Kim who becomes a technologically-advanced “xombi” after his body is infused with nanites; it remains one of the only comic book titles to ever focus on an Asian American male superhero protagonist.

That same year, Milestone also launched Shadow Cabinet, an Outsiders-esque team of covert superheroes. The team included several characters within the Middle Eastern, Asian and Asian American diaspora including: Blitzen, a Japanese speedster in a lesbian relationship with fellow Shadow Cabinet member Donner; Iron Butterfly, a Palestinian ferrokinetic; and the powerful and mysterious precog Dharma, leader of the Shadow Cabinet who appears to be of South Asian American descent.

Milestone is notable in the comics industry for launching under an unprecedented deal with DC Comics; DC agreed to serve as Milestone’s publisher and distributor while Milestone creators would retain complete editorial control and copyright. This gave Milestone properties immediate and incredible reach with comic fans, while still allowing the studio space to build a nuanced and distinct comic book universe — dubbed the Dakotaverse — which permitted characters to tackle subjects that mainstream comics wouldn’t dare touch: namely, the consequences of their non-White race.

And, although Milestone — and its eventual Worlds Collide crossover event that brought many of its non-White characters into the mainstream DC pantheon — is the origin for many of today’s non-White superheroes, the Dakotaverse is one of the most important contributions that Milestone made to the comic book industry. Even with its efforts to diversify its characters, DC and Marvel comic universes are inherently White spaces that promote a message of racial indistinctiveness, where differences in racial and class background are largely meaningless. Snoopy Jenkins has powerfully written about how the mainstream superhero is innately a White male power fantasy, and how race should shape the choice to don superhero spandex; yet, in the universes of DC and Marvel, the White privilege of vigilantism is never questioned.

Not so in the Dakotaverse, where race and class are real problems and where heroism and villainy are cast not in the stark morality of black and white, but in shades of grey. Icon, a Superman pastiche, survives chattel slavery with the lesson that he should hide his powers rather than to expose himself as different; he instead assimilates with the White ruling class and accumulates personal wealth. Only through the exhortations of the teenaged Rocket, who grows up in inner-city poverty, does Icon decide to use his superpowers to become a hero. For Icon, the choice do put on a cape was not an obvious one, and the villains he faces represent the institutionalized impacts of crime and poverty on urban communities.

In 1997, after a four-year run, Milestone shut down its comic book publishing efforts, largely due to the comic book industry crash of 1994. However, Milestone also suffered from a ghettoization of its publications by its professional peers; it was treated by industry insiders as “comics for blacks” with limited appeal to non-Black audiences, and most of its early sales were ignored or dismissed by comic journalists. Only with McDuffie’s later success in promoting Black characters (including several of his own creation) in DC comics did McDuffie receive the broader accolades he deserved. McDuffie is responsible for resurrecting the popularity of JLA members John Stewart/Green Lantern and Vixen during his run on the Justice League animated series, and he also used his position to better incorporate characters Icon and Rocket into the DC animated universe. McDuffie also penned 11 episodes of a Static Shock animated series, based on his character of the same name.

When McDuffie died suddenly on February 21, 2011, it seemed like we lost a legend right at the cusp of an historic moment for the fight to diversify comics. It seemed like we lost McDuffie just when mainstream comics was starting to recognize the need for more superheroes of colour, and we lost the man who would help to achieve that goal with understanding and nuance.

The Washington Post reports that McDuffie’s colleagues — Reggie Hudlin, Denys Cowan, and Derek Dingle — are interested in reviving Milestone Media, with an eye to restart the Milestone Comics studio. Their reasons are quite simple: they’re dissatisfied with how mainstream comics are approaching racial diversity. Criticizing the same approach that I’ve dubbed the “Cowl Rental”, the three hope that a Milestone 2.0 can push beyond the current trend of injecting comic diversity by shoe-horning minority characters into the cowls of popular White superheroes with hopes that the prestige of the White character will rub off on the minority successor. Reports the Washington Post (emphasis added):

In recent years, major comics publishers have aimed to make real strides in character diversity. Marvel, for example, has introduced a half-black/half-Puerto Rican Spider-Man (Miles Morales); a black Captain America (formerly the Falcon/Sam Wilson); and a female Thor. DC Comics has made similar advances with such existing characters as Green Lantern John Stewart, and by introducing Batwing (a black member of Batman’s team of crimefighters) during the debut of the New 52, and announcing that there will be a black Power Girl (Tanya Spears).

Yet Cowan says that putting a character of color in a well-known, previously white mantle doesn’t hold the same impact as creating a new wave of heroes for an ever-diverse readership and new generations of fans.

“There are all kinds of challenges that are facing people of color — that part hasn’t changed,” Cowan tells The Post’s Comic Riffs. “What has changed is, there are a lot more characters of color in comics. What we feel is now, Milestone is necessary because of the types of characters that we do, and the viewpoint that we come from.”

“We’ve never just done black characters just to do black characters,” he continues. “It’s always come from a specific point of view, which is what made our books work. What we also didn’t do, which is the trend now, is [to] have characters that are, not blackface, but they’re the black versions of the already established white characters — as if it gives legitimacy to these black characters in some kind of way — [that] these characters are legitimate because now there’s a black Captain America.

“Having been a creator of these characters and a consumer, I always looked at it like, ‘Well, geez, couldn’t you give me an original character?’ ” Cowan adds. “Black Panther worked because he was original. Static Shock worked because it was an original concept. It’s a good time to come back and reintroduce original characters, as well as some new ones.”

Importantly, a Milestone 2.0 is not just important because it can serve as an incubator for new, original minority characters, but also because it can help to incubate minority comic book talent by supporting projects that deal with subject matter that mainstream comics considers implicitly “edgy” for its non-White content. Several of today’s prominent minority comic book creators got their start with the minority-owned Milestone Media. A thriving Milestone 2.0 should offer similar opportunities for aspiring minority comic book artists and writers seeking to break into an industry that remains disturbingly White male-dominated.

Hudlin, Cowan and Dingle also emphasize that they hope a new Milestone Media will not focus just on comics, but will also support works in multiple mediums:

“One thing I’ve always loved about the company [is] even the name, Milestone Media,” says Hudlin, who has written for Black Panther, the Stan Lee-era Marvel character who so inspired McDuffie to pursue comics as a career. “It’s going to be a company that will not just be doing comic books. [We’re] going to be working on a lot of different mediums.”

Hudlin says that Milestone Media will bring back many of the classic characters, as well as introduce new heroes. (It has been announced that a live-action Static Shock series is in the works from Warner Bros., which owns DC Comics.)

There’s still no word as to how far along Hudlin, Cowan and Dingle are in resurrecting Milestone Media, but they tell the Washington Post that they hope to have new art to show by this year’s San Diego Comic-Con.