Last week, the Nobel committee announced that this year’s Nobel Peace Prize would be jointly awarded to two powerful activists within the Asian diaspora for “their struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education.”

17-year-old Pakistani education justice activist Malala Yousafzai skyrocketed to global fame for speaking out against the Taliban for their policies banning education for girls throughout her native Swat Valley, an area in the northwest region of Pakistan; her activism for the right of girls to have access to educational opportunities prompted an assassination attempt in 2012 that nearly claimed her life. Yousafzai (note: I use Yousafzai’s last name because female activists are often infantalized and dismissed by media coverage that selectively uses first names to refer to women where they do not for men) survived a gunshot to the head. Yet, her advocacy was undeterred and she has since become, quite legitimately, the face of female educational justice around the world. With last week’s announcement, Yousafzai becomes the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in history.

Kailash Satyarthi is a child rights advocate who founded Bachpan Bachao Andalan, a non-profit organization that focuses on child labour and human trafficking throughout South Asia. BBA organized the world’s largest campaign against child labour in 1998 in the form of its Global March Against Child Labour, and estimates that through its direct action has rescued over 80,000 children from bondage since the group’s founding in 1980.

This year’s award of the Nobel Peace Prize to two outspoken South Asian advocates is an important moment for Asians and Asian Americans: it highlights the long tradition of social justice activism in Asia which is often lost in the stereotype of Asians and Asian Americans as politically meek and socially backwards. It is further a watershed moment for the cause of global Asian feminism.

This year’s award of the Nobel Peace Prize to two outspoken South Asian advocates is an important moment for Asians and Asian Americans: it highlights the long tradition of social justice activism in Asia which is often lost in the stereotype of Asians and Asian Americans as politically meek and socially backwards. It is further a watershed moment for the cause of global Asian feminism.

The link between Malala Yousafzai’s work and international feminism is obvious: although the global gender gap in male vs. female access to education has been closing since the 1970’s, throughout many parts of Africa and South Asia, boys still outnumber girls in school. In 2010, the UN estimated that only 75 girls were in school for every 100 boys in Pakistan. In neighbouring Afghanistan, the situation for girls is even more dire: only 50 girls attend school for every 100 boys. In addition to the global gender disparity in educational access, the UN is also reporting that drops in international aid for primary school education has resulted in a veritable stagnation in the rate of childhood education throughout the world.

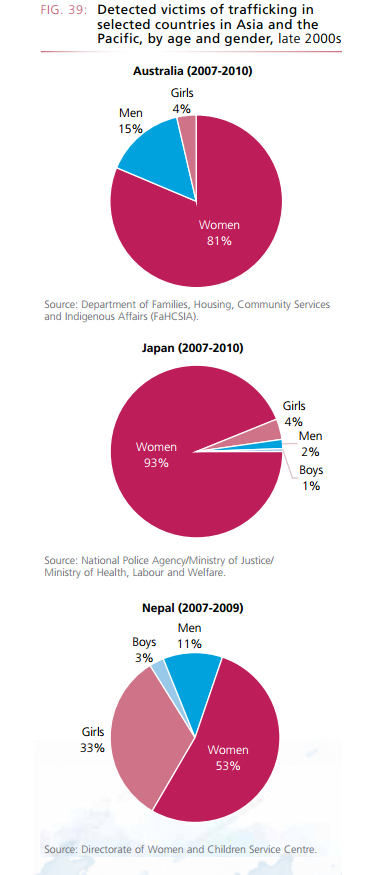

Thus, instead of going to school, many children throughout the world are forced into the workforce, where they become vulnerable to labour exploitation and even human trafficking. These issues are ones that are both innately feminist and also that receive too little attention from political activists (even those of us who identify as AAPI) in the West: in 2012, the United Nations estimated that nearly 21 million people globally are victims of human trafficking — nearly 30% (or 6.3 million) of them are children. In Asia, between 80-90% of trafficked humans are women or girls for many countries. The vast majority of these trafficked women and girls are forced into bonded labour or sexual exploitation either in Asia or exported to other parts of the world, including the Americas where Asians makeup nearly 30% of all humans trafficked to the region. Thus, while Satyarthi’s work is nominally gender neutral, the issue that he and his organization combats is inherently a matter of international women’s and girls rights, and one that deeply impacts the America politic, whether we like to admit it or not.

Thus, for many reasons, I am excited that Yousafzai and Satyarthi will receive this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, and in so doing shed an important spotlight on an issue that intersects strongly with Asian feminism.

Yet, there are also some reasons to be critical. Some wonder why these two activists — powerful in their own right — are forced to share a Nobel Peace Prize (although to be fair, most of the Nobel Peace Prizes were awarded in the last twenty years either jointly to multiple laureates or to an organization than were were awarded to a single individual). Grace Hwang Lynch expresses concern over the dilution of Yousafzai’s impact with the announcement that she would share the award with Satyarthi:

Part of me is rankled by the fact that Malala must share the award. With no disrespect to Satyarthi’s accomplishments, it just seems to water down the honor, or perhaps suggest that the committee doesn’t want to make too bold of a statement against extremism

Lynch also discusses how Yousafzai’s activism may be popular because it, in part, has been framed as a symbol of Muslim anti-female oppression to justify Western militarism and Islamophobia; Lynch cites Amina of Muslimah Media Watch who writes:

”…the media discourse about Malala often insinuates that her commitments to women’s education are derived from Western influences and values juxtaposed, again, against the backdrop of stereotypes that characterize Muslim women as downtrodden and dreaming to be saved by the white knight in shining armour.”

Max Fisher of the Washington Post is more scathing in his criticism of Yousafzai’s popularity:

Western fawning over Malala has become less about her efforts to improve conditions for girls in Pakistan, or certainly about the struggles of millions of girls in Pakistan, and more about our own desire to make ourselves feel warm and fuzzy with a celebrity and an easy message. It’s a way of letting ourselves off the hook, convincing ourselves that it’s simple matter of good guys vs bad guys, that we’re on the right side and that everything is okay.

Some writers have gone further to ask why Yousafzai’s activism is celebrated while the story of Nabila Rehman remains virtually unknown.

Rehman is an equally powerful teenaged Pakistani female voice, but Rehman’s cause is not the international gender disparity in schooling, but the human civilian cost of American drone strikes. At the age of 8, Rehman survived a CIA-operated drone strike that wounded three of her siblings and killed her grandmother, and has since become a vocal opponent of America’s drone program — at ten years old, Rehman traveled to Washington DC to testify before Congress. Yet, Nabila Rehman is not even in the running for a Nobel Peace Prize, even though her work is much more in keeping with Alfred Noble’s original vision for the award which was to promote global disarmament.

Others also question why Satyarthi’s decades of work has received so little international and Western attention despite the powerful impact of his advocacy throughout Asia, underscoring how little a priority most “First World” nations place on the thriving international market in human trafficking. Satyarthi’s organization has drawn significant attention to the thriving black market of human trafficking that victimizes thousands annually — most of them women. Yet, Satyarthi’s name is virtually unknown.

In the end, no Nobel Peace Prize announcement is not without its share of controversy — anyone remember the hullabaloo surrounding the award of the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize to President Barack Obama, whose presidency is now marked by an unprecedented reliance on unmanned drone strikes? For me, Satyarthi and Yousafzai’s joint receipt of the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize is significant for the impact this award will have on drawing attention to the issue of child rights and trafficking, which represents a prominent intersection of Asian feminism with global educational justice. For that alone, this is a moment worth celebrating.