Today is Labour Day, a national day to commemorate the role of the American labour movement in shaping contemporary US political and personal life. For AAPIs, our history is closely linked with and can often be told through the fight for labour rights; yet, as Professor Glenn Omatsu points out in this AAPI labour studies class syllabus, our contributions to the labour movement are often overlooked.

Like other immigrant groups in America, the history of Asian Americans is essentially a labor history and part of the history of working people in America fighting for justice, equality, and the expansion of democracy. Yet, in contrast to the labor histories of European immigrants, the labor struggles of Asian immigrants and Pacific Islanders are often excluded from traditional accounts of American labor history.

While you are out celebrating Labour Day today, please take a minute to remember these two historic moments for AAPIs in the labour movement.

1. Filipino American farm workers who lead the charge for workers’ rights in California and other parts of the West Coast.

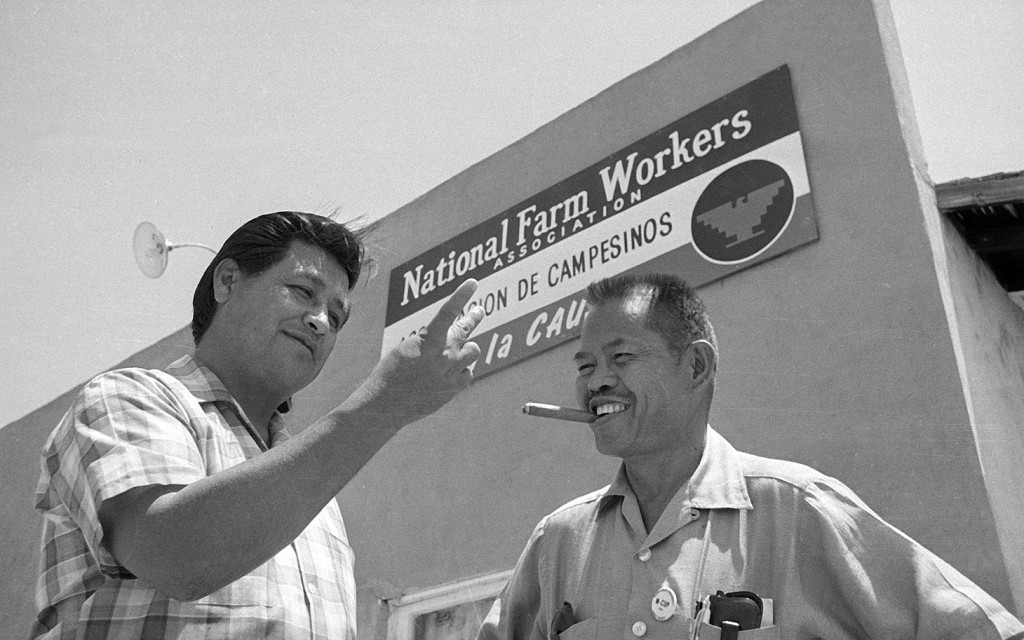

The work of Mexican American labour organizer Cesar Chavez is well-known, and the subject of an eponymous big-budget biopic released in theatres this year and on DVD earlier last month. Yet, the movie was also a source of controversy for its papering over of the contributions of Filipino American labour activists contemporary to Chavez and who allied with Mexican American workers throughout parts of the West Coast to organize strikes in the struggle for migratory labour rights. In this year’s Cesar Chavez, Filipino Americans are either invisible or bystanders; yet in reality, Filipino American unions were powerful partners with Chavez’s National Farm Workers Association (NFWA).

Throughout the early twentieth century, Filpino American migrant workers arrived on the shores of America to meet the demands for cheap agricultural labour. Emigrating from the Phillipines (which had recently been claimed as an American territory), their immigration was less restricted than that of Chinese, Japanese, or Koreans whose entry had been in essence halted by racist exclusionary laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act. Thus, between 1920 and 1930, the Filipino American population rose in America by 1900%, andby 1930, over 100,000 Filipino workers were living in America — most as part of the agricultural sector’s migratory labour force — to meet the sudden demand for cheap labour. In so doing, Filipino Americans became positioned at the forefront of America’s growing fight over labour rights.

Throughout the West Coast and Hawaii during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, agricultural workers worked under deplorable conditions: long grueling hours were compensated with low (and often racially unequal) pay. In contrast to the stereotype of the meek and apolitical Asian American (a stereotype that, to be fair, was only popularized in America in the post-1980’s), Asian American low-skilled labourers of all ethnicities — including Filipino Americans as well as Chinese, Japanese and Korean workers before them (please see the linked post to learn more about turn-of-the-century Hawaiian Chinese and Japanese labour unions) — organized into some of the nation’s first and most powerful labour unions.

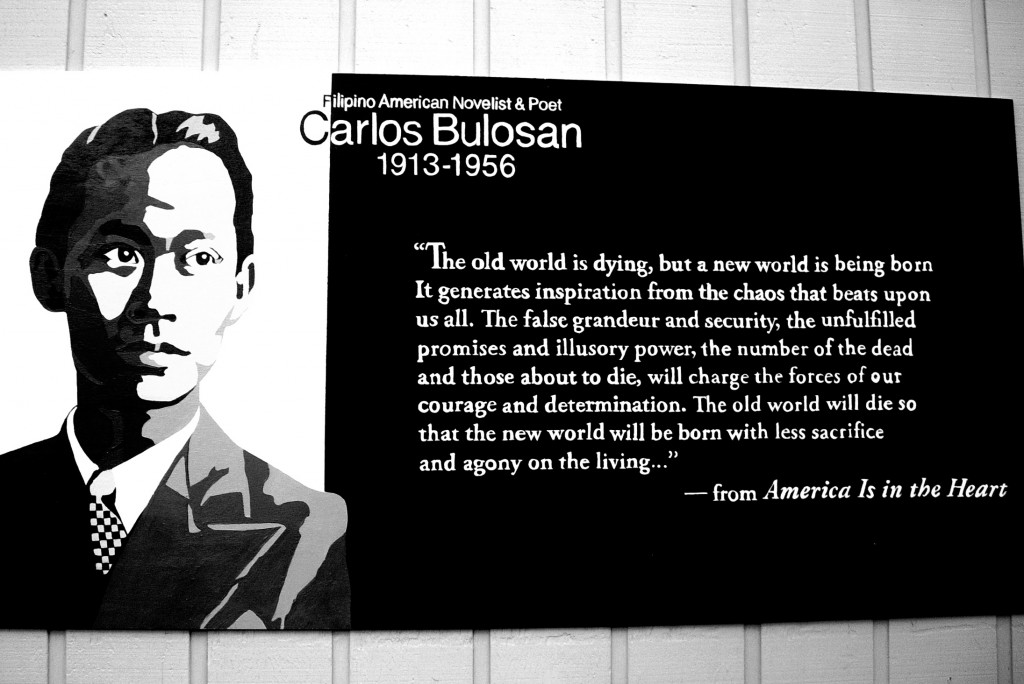

Although non-Asian Americans might know mostly of the work of Carlos Bulosan, a Filipino American poet and labour activist whose landmark semi-autobiographical book America Is In the Heart explored themes of labour rights and colonialization through the lens of his life as a migratory farm worker on the West Coast during the 1930’s, less well known are the contributions of Filipino American union leaders like Philip Vera Cruz and Larry Itliong and others who are among the most influential of the community’s labour activists.

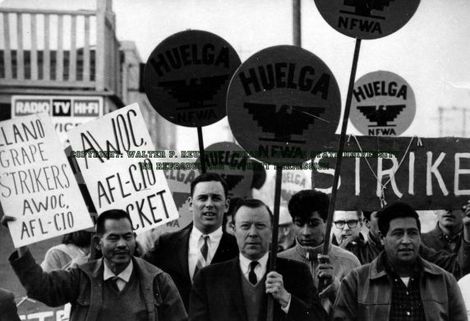

Vera Cruz and Itliong co-founded the predominantly Filipino American farmworkers’ labour union known as the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). On September 8, 1965, AWOC met in Delano, California to discuss the low wages paid to farm workers by table grape growers on the West Coast — the wages were among the lowest in the nation — and decided to strike. Vera Cruz described the decision to strike thusly:

On September 8, 1965, at the Filipino Hall at 1457 Glenwood St. in Delano, the Filipino members of AWOC held a mass meeting to discuss and decide whether to strike or to accept the reduced wages proposed by the growers. The decision was ‘to strike” and it became one of the most significant and famous decisions ever made in the entire history of the farmworkers struggles in California. It was like an incendiary bomb, exploding out the strike message to the workers in the vineyards, telling them to have sit-ins in the labor camps, and set up picket lines at every grower’s ranch… It was this strike that eventually made the UFW, the farmworkers movement, and Cesar Chavez famous worldwide.

Eight days after AWOC decided to strike, Chavez’s National Farm Workers of America union voted to join the strike, and the Delano grape strike became a watershed moment in the labour history of America. For five years, AWOC and NFWA (which merged in 1966 to form UFW) organized a sustained series of pickets and boycotts, along with direct protest action, to pressure grape growers to come to the collective bargaining table while bringing the plight of agricultural workers on the West Coast to the attention of mainstream America. The strike lasted five years until 1970, when the protest culminated in a labour agreement signed between grape-growers and union representatives (including both Chavez and Itliong) that affected nearly 10,000 farm workers in the industry.

The Delano grape strike is credited as a pivotal moment in labour history as an example of creative protest tactics leading to a significant victory in favour of collective bargaining; and, it all started at the Filipino Hall community centre at 1457 Glenwood St. in Delano, California.

2. Chinese American garment workers who have been defending garment workers’ rights for over seventy years.

Chinese American garment workers labour under difficult conditions throughout much of the country, in backroom factories where workers might be paid mere pennies to sew buttons by the thousands under back-breaking conditions. This sort of work employs — and sometimes exploits — immigrant workers, including Chinese American women. Yet, Chinese American women have also throughout history defied stereotypes to act as strong and outspoken defenders of the rights of garment workers.

In 1938, the International Ladies’ Garments’ Workers Union (ILGWU) began organizing in San Francisco Chinatowns, establishing the Chinese Ladies Garments Workers Union Local 361. That year, under the guidance of national ILGWU organizers, union members including Sue Ko Lee — a button hole manufacturer who earned just 25 cents an hour — organized a massive strike and picket line against National Dollar Stores factories that lasted 15 weeks. Eventually National Dollar Stores gave in, and the Lee and others were able to negotiate improved wages, a forty-hour work week, and improved safety conditions. While this negotiation ultimately failed to make lasting impact for garment workers in San Francisco — just a year after the contract was negotiated, the management company for the factory went out of business nullifying the contract — this early strike helped racially integrate Chinese Americans into the ILGWU leadership, and brought collective bargaining to Chinatown garment factories where garment workers were often exploited.

To learn more about this pivotal moment in San Francisco Chinatown history, read Unbound Feet by Judy Yung.

Over fifty years later, ILGWU helped organize a second massive boycott and strike involving Chinatown garment workers. 27,000 Chinese American garment workers in NYC held massive rallies and a strike over the spring and summer of 1982. In an article associated with a 2012 Museum of Chinese Americans exhibit on the subject:

“They’re united by the fact that they were poor and didn’t speak English,” [Rose] Imperato [of the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition] explains. “They were easily forgotten and had to stand up for their rights.” Striking was especially difficult for Chinese garment workers for other reasons. First, most of the employers were Chinese themselves, which produced awkwardness in a community that valued social order and ethnic solidarity. Second, stubborn patriarchal notions discouraged women from challenging authority, even within activist circles. “Labor organizations were extremely male-dominated,” remembers May Chen, who worked for the hotel and restaurant workers’ union at the time. “A lot of the garment workers, their husbands really disapproved of their wives’ activism, thinking it was just gossiping and getting into trouble. They wanted their wives to go back and take care of the children.”

But the ILGWU was undeterred. Union officials went to every corner of Chinatown, carrying plastic bags full of Chinese-language leaflets, urging men and women alike to show up to the rally. On the day of the first strike, June 24, Columbus Park was filled “body to body,” says Chen. “The speeches were so captivating and lively. The Cantonese idioms would just rile up the crowd. People were cheering and clapping. Women whom I knew as kind of shy were loud and angry. I remember some my normally quiet ESL students pushing their kids in baby carriages around the block.” There was no longer any ambiguity that traditionally-raised Chinese women would stand up to male authority when their class interests were at stake.

Eventually, the 1982 Garment Workers’ strike resulted in a signing of a union contract between workers and employers. The strike is described on the Cornell ILR college website and is documented in the 2006 book “Holding Up Half the Sky” by Xiaolan Bao.

Today, the ILGWU continues as part of Workers’ United and is focused predominantly on advocating on behalf of garment workers in developing nations (including parts of Asia like Bangladesh — home to many factories that create garments for American consumers) where unsafe, sweatshop labour conditions remain common.

Have your own favourite moment related to AAPIs & the labour movement? Add them to the comments section below!