I was having dinner earlier this week with a member of my extended family when the topic of race-conscious affirmative action and SCA-5 came up. My family member (who is not Asian American) was surprised to learn that I support affirmative action; he was under the impression that all Asian Americans were monolithically opposed to race-conscious admissions considerations. “What?” he asked, somewhat teasingly, “don’t you want Asians to be able to get into college?”

I have written extensively about how affirmative action doesn’t prevent Asian Americans from accessing college: 1) affirmative action does not permit race to be used as a determinative factor in admissions decisions so any use of affirmative action to deny Asian American access to college based on race alone is unconstitutional, 2) there are several ethnic groups within the AAPI diaspora, including Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, who are contemporary active beneficiaries of race-conscious affirmative action, 3) East Asian Americans (e.g. Chinese Americans) who have been present in America longer than other AAPIs have traditionally been active beneficiaries of race-conscious affirmative action particularly in the mid-twentieth century when Chinese and Chinese American students were actively recruited to elite universities to end racial segregation; only in the last two or three decades have we no longer received additional consideration under race-conscious affirmative action, and 4) all students, regardless of race, benefit from the diverse student life that is achieved through race-conscious affirmative action considerations in college admissions through broader exposure to different viewpoints as well as better preparation for an increasingly globalized market.

All this aside, there is a persistent myth within the American political landscape that Asian Americans are universally opposed to affirmative action. Yet, nothing could be further from the truth. If anything, the affirmative action issue is one that highlights the diversity in Asian American political thought.

During the SCA-5 debate, a broad coalition of progressive and liberal Asian American advocacy groups who stood in support of affirmative action found themselves pitted against a vocal community of Asian Americans organized predominantly through Asian-language forum boards and ethnic media outlets. In the mid-nineties, two-thirds of Asian American voters voted against Proposition 209 and in favour of preserving race-conscious affirmative action in California. Several large and small surveys have reported a similar two-to-one breakdown in support for affirmative action among AAPIs, including the National Asian American Survey (NAAS), the largest survey to-date of our community. In NAAS’ 2012 study, Dr. Karthick Ramakrishnan’s team surveyed over 4,000 registered AAPI voters from around the country, asking their opinion on a battery of contemporary political issues; they found that 75% of surveyed Asian Americans and 67% of surveyed Pacific Islanders support affirmative action.

Taken together, these data — compiled from multiple sources yet all showing roughly the same breakdown in support for affirmative action — support the conclusion that approximately two-thirds of AAPI voters support affirmative action, while the remaining one-quarter to one-third oppose it. This is a finding that flies in the face of the presumption made by many asserting that Asian Americans are universally opposed to affirmative action.

To reinforce this finding, NAAS commissioned the Field Research Corporation to conduct an updated study, focused specifically on whether or not AAPI attitudes towards affirmative action had shifted in the wake of the SCA5 shakedown of earlier this year: virtually the entire state of California was wrapped up in a debate over campus diversity that saw its fair share of strong opinions, impassioned arguments, and more than a little bit of misinformation and flat-out over-sensationalized hyperbole.

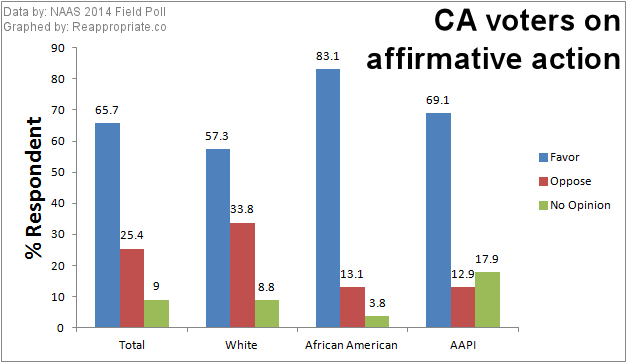

The findings of the survey are surprising in that there has been very little discernible movement in AAPI attitudes towards affirmative action in the last two years, despite a very public Asian American outcry against it. In NAAS’ 2014 survey of AAPI California voters, released yesterday morning, 69% of AAPI voters still support affirmative action (compared to 83% African Americans and 57% Whites).

It appeared during the SCA-5 debate of this past year that the majority of those who were organizing efforts against the state constitutional amendment were Chinese Americans (and who were using the term “Asian American” and “Chinese American” both ethnocentrically and synonymously); so, perhaps if NAAS disaggregated the AAPI numbers down further by ethnicity, it might reveal a strong Chinese American opposition?

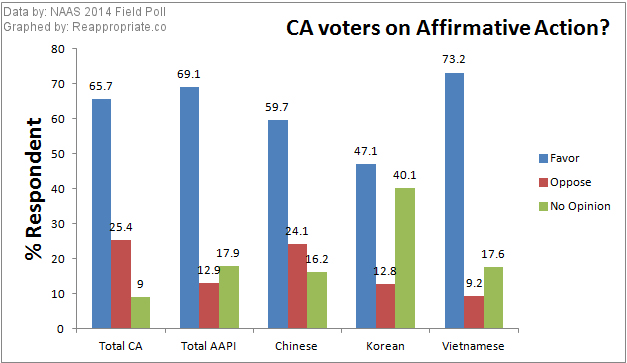

Yet, when these numbers are disaggregated by ethnicity, NAAS finds that Chinese Americans are still majority in favour of affirmative action, as are Korean Americans and Vietnamese Americans (this breakdown addresses three of the five largest AAPI ethnic communities in the state of California).

(An important point from this graph is that Korean Americans are more than twice as likely to have “no opinion” on affirmative action as are respondents of any other race or ethnicity. This strongly suggests to me that 1) the experiences of one or two major ethnicities — in this case Chinese Americans — have been inappropriately generalized to the larger AAPI diaspora, and 2) that there has been a significant and lamentable failure in political outreach from both sides of the SCA5 debate to engage non-Chinese AAPI voters like Korean Americans. That lack of voter outreach and consequent issue apathy will only exacerbate our community’s existing voter turnout problem, and cannot continue.)

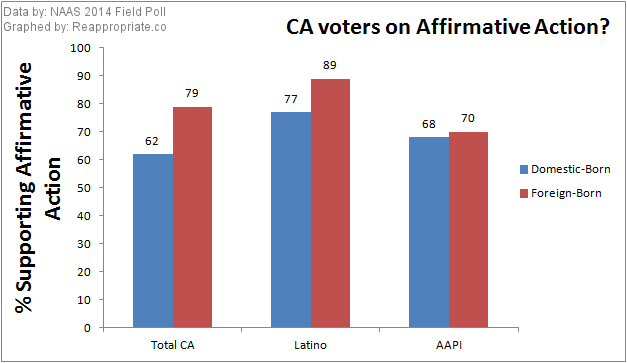

NAAS went on to consider AAPI voters by gender, age, and even by birthplace; again, there was no group of AAPI voters that were predominantly opposed to affirmative action.

While this clear two-thirds support for affirmative action among AAPIs is heartening for me, it doesn’t particularly influence my personal opinion on affirmative action: I support affirmative action because I believe it is the moral and progressive position, not because it might be (or might not be) the popular position. On the other hand, these findings appear to distress opponents to SCA-5, who adamantly assert that most Asian Americans oppose affirmative action. In May, conservative California State Senate candidate Peter Kuo who is campaigning on the affirmative action issue (and who recently opposed San Francisco’s landmark ban of anti-Asian abortion restrictions) told Mintpress a tall tale about monlithic AAPI opposition to SCA-5. Mintpress reports:

[Peter Kuo] insists that Asian Americans and other minorities he speaks to “all have the same opinion in this. I ask them the same question, ‘Do you want affirmative action here?’ One hundred percent of them say ‘No.’ They don’t want government helping to get them where they want to go.”

“We repealed it in 1996,” he said. “Don’t bring it back.”

Others argue that it is only the culturally out-of-touch liberal Asian American media academics and elite (which apparently includes me) who support affirmative action; “You’re simply not acknowleding most of the community“, Byron Wong of BigWOWO.com says of me in the context of SCA-5 (emphasis added). In regards to NAAS’ 2012 and 2014 survey findings, which refute the “one hundred percent” opposition cited by Peter Kuo, opponents instead question Dr. Ramakrishnan by asserting that he biased his findings based on his own personal prejudices on affirmative action. Byron Wong says:

I already pointed out that I don’t trust Karthick. That should have been a perfectly legitimate reason not to waste my time on him; I think it ought to be perfectly acceptable for me to reject ONE survey based on who is running it. But yes, I finally did look at the methodology, and it proves that I was right in my assessment, never mind my questions over the way it was carried out.

Wong and others cite concerns about NAAS’ affirmative action question wording (“Do you favor or oppose affirmative action programs designed to help blacks, women, and other minorities get better jobs and education?“), arguing that it is “loaded“. Yet, not only was this question wording adapted from a virtually identical question used by Pew Research Center (a non-partisan think tank that conducts hundreds, if not thousands, of similar surveys) in 2002 (and remains similar to the wording of their more contemporary affirmative action question), but in 2012, NAAS deliberately asked the question in multiple formats (using more or less preamble) in order to assess how the question wording impacted survey responses; they found virtually no impact of how the question was asked on the answer. Finally, as mentioned above, NAAS survey results confirm previously published AAPI opinions on affirmative action conducted on smaller scales. Bottom line: there is simply no reason to suspect the NAAS outcome has been biased by the investigators’ alleged partisan agenda. And, in the absence of obvious methodological problems, the survey results must be accepted.

So, if we are to believe that (once again) science shows two-thirds support for affirmative action among AAPIs, how can we interpret the impassioned and vocal opposition to SCA-5 earlier in the summer: an outcry so potent, it literally “killed the bill”?

I don’t have any issues reconciling this: that a majority of AAPI voters support affirmative action doesn’t negate the fraction of AAPIs who oppose it: 12.5% of California’s 5.3 million AAPI residents is still approximately 650,000 AAPI California voters who oppose affirmative action. Get even a fraction of those 650,000 in the same place, and it can still be an intimidating political show of force sufficient to pressure local elected officials. In fact, this is exactly how minority politics has operated against a numerical disadvantage in America for over a century.

The better question is why a one-third minority of AAPI voters who oppose affirmative action might fail to recognize that they might be in the minority? What might lead affirmative action opponents to perceive that they are not just in the majority, but in an overwhelming majority?

The modern political landscape is characterized by an increasing balkanization of thought, facilitated by the increasing power of individuals to choose to amplify voices that agree with one’s own opinions, and to block voices that disagree. Even mainstream news outlets — whether MSNBC or Fox News — are less interested in providing straight journalism over editorialized commentary that caters to audiences of specific political affiliation. Whether liberal or conservative, progressive or neo-Nazi, it is possible now to insulate oneself entirely within personalized media echo chambers that only reinforces one’s own personal viewpoints and creates the illusion that those opinions are shared by a majority of others.

The internet exacerbates this problem: we can now simply tune out, block, ban or unfriend people who fail to share our political outlooks — the digital equivalent of plugging one’s ears to things we don’t want to hear. I would assert that most of us are operating within intellectual and political echo chambers to some degree. For Asian Americans, this effect might only be enhanced by the linguistic isolation that affects nearly one-quarter of our community‘s households; linguistic isolation not only promotes geographic segregation within ethnic enclaves, but can also limit voter education to what is available primarily through in-language ethnic media outlets (which this past year covered the SCA-5 debate heavily, and often with an editorial stance in opposition).

But, intellectual balkanization is lethal for sophisticated argumentation. It is only through reasoned disagreement that one explores the logic of one’s own opinions and identifies fallacies, leading to either strengthening or abandonment of one’s own arguments. In the absence of forced exposure — or self-exposure — to a challenging peer, assumptions and misinformation persists and even dominates the dialogue; we routinely observed this problem in California this year from SCA-5 opponents who also argued that few “non-government” and “non-academic” AAPI within their personal social networks expressed support for affirmative action.

This observation regarding the detriments of intellectual balkanization is highly relevant to the debate over affirmative action: it is precisely this problem that diversity advocates hope to combat through underscoring the “compelling interest” of campus diversity alongside other interests in the college admissions process. The purpose of secondary education is to guide students towards developing a broader critical understanding of the world at-large, and the synthesis of multiple viewpoints related to any specific field of interest; this is a specific analytical skillset that is increasingly necessary in our information-based and globalized economy. This is also a mission that is greatly facilitated by a diverse student body

In a diverse student body, intellectual balkanization is dismantled through routine formal and informal interactions with highly-qualified fellow students of different personal and academic backgrounds. Meanwhile, a culturally and racially homogeneous college campus — even one populated by remarkably intelligent individuals — only replicates the same echo chamber effects found in our off-campus (and online) worlds, and are directly antithetical to the goal of secondary education. When one is not exposed to different viewpoints, one’s own ideas suffer. A non-diverse student body is one that fails its students.

NAAS’ 2014 update of their 2012 national survey reveals something we kind of already knew: that AAPI voters (and particularly those living in California) are majority in favour of affirmative action. But the interpretation of these data require that we not conclude a monolithic or universal opinion on this subject: like most communities, AAPIs do not think monolithically on this or any other issue. Instead, there is a deep divide within the AAPI community over affirmative action, one with impassioned arguments coming from both sides. What we must take away from NAAS’ 2014 survey is not to focus just on what the majority opinion is, but to respect the difference, and to maintain the pursuit of respectful debate over those differences. That also means that we — affirmative action supporters within the AAPI community — must work harder to mobilize in light of that difference; an impassioned minority can clearly sway political outcomes if we do not.

AAPI aren’t all the same, so we need to stop allowing ourselves (or others) to treat our community as if we all think — or vote — the same.

Correction: An earlier version of this post reported national, not California-wide, AAPI demographics.