Last Saturday, legendary Star Trek actor and activist George Takei arrived at a charity event with a bandage on his face, ContactMusic.com reports; the actor was recovering from having had a cancerous skin growth removed from his face earlier in the week. The cancer was detected in its early stages during a routine visit to the doctor the week prior, and removed.

Takei reportedly said, “I went to my doctor for my physical last week and he detected an early sign of skin cancer here. He cut it out and that’s why I’m wearing this (bandage).”

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in the United States, with over 3.5 million new cases diagnosed each year. But, for AAPI, skin cancer is a particularly significant health concern: AAPI have among the lowest survival rates from skin cancer of any race or ethnicity.

Skin cancer can come in many forms, with melanoma being the most well-known and most common subtype. However, while significant improvements in public education, early diagnosis, and treatment options for skin cancer has resulted in the survival rate jumping by about 30% (from 68% in the 1970’s to about 92% today) for Whites, similar advances are not seen among minority patients diagnosed with skin cancer. This translates to a significant racial disparity in skin cancer survival.

In one study, AAPI had a 5-year and 10-year survival rate following skin cancer diagnosis of 70.2% and 54.1% (compared to the national survival rates of 80.3% and 67.5%, respectively).

Part of this low survival rate for Asian Americans (and other minorities) is associated with a cultural resistance towards recognizing skin cancer as a prominent issue among minorities: while we know that melanin protects the skin from the damages of UV radiation, darker skin is not impervious to skin cancer. Black and AAPI have the lowest incidence rate of skin cancer of all race and ethnicities, but in both communities, studies also show that African American and AAPI patients — who are more likely to be diagnosed with the more severe form of melanoma, acral lentiguous melanoma — also arrive at clinics with far more advanced and aggressive versions of the disease, which further worsens the patient prognosis.

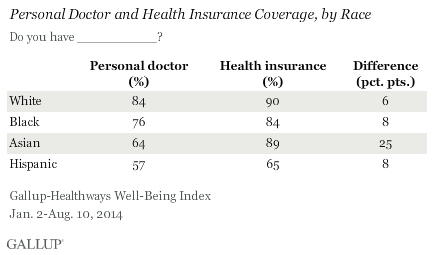

Part of the problem may have to do with ongoing spottiness of healthcare coverage within minority communities. Blacks, Latinos and Asians all have lower rates of being insured by a healthcare plan than do White Americans, and although a recent study by the Center for American Progress and AAPI Data reveals that Asian Americans enrolled in new healthcare plans under the Affordable Care Act, another recent Gallup poll adds a layer of complexity: according to Gallup, Asian Americans are the least likely to self-report having a regular personal doctor, even when they are covered.

While the rest of Gallup’s article is a bit on the obnoxious side (no, Asians aren’t using traditional Chinese medicine to make up for not going to the doctors’ office), this survey result suggests that today’s Asian Americans may have less access to the kinds of routine physicals that are essential for combating a disease like skin cancer, which is most effectively treated by early diagnosis and removal. It was a routine checkup, after all, that caught George Takei’s cancer last week.

Skin cancer, particularly melanoma, has a high survival rate if caught early through routine doctor visits. The low survival rates of AAPI when it comes to melanoma can be largely combated through increased community education about skin cancer and other diseases, and better access to in-language healthcare resources. Concluded Bellew et al in a 2009 study:

There is evidence that delays in seeking diagnosis and treatment are major contributing factors [to low survival rates from melanoma among communities of colour]. As a result, educational efforts should be put in motion to decrease delays in diagnosis. Skin cancer is no longer attributed solely to fair-skinned individuals with light-colored hair and eyes. Skin cancer has a new face, and that face is multicultural. Increasing awareness about [melanoma] in both Caucasian and non-Caucasian populations may facilitate early diagnosis and treatment, and ultimately will save lives.