A new study published two months ago in the American Journal of Public Health delves for the first time into the complex intersection of race and sexuality in mental health issues affecting the nation’s youth, and their results are telling.

Using survey data from 2005-2007, the group assessed the mental health outcomes of over 70,000 teens living in 14 districts, and which included over 6,000 sexual minorities. The group was able to for the first time disaggregate depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among teens by race and gender, and particularly with regard to often-times invisible racial groups — multiracial and Alaska Native / Pacific Islander youths.

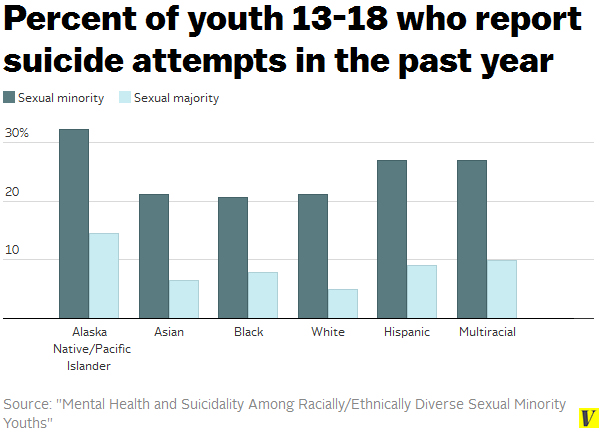

In their study, the group found that regardless of race, sexual minorities are about twice as likely as sexual majorities to feel sad, and about three or four times as likely to self-harm or attempt suicide. The absolute numbers are also striking — half of LGBTQ youth between ages 13 to 18 feel an unusual degree of sadness, and one in three have attempted suicide. One in three.

This finding can be nothing other than a profound and poignant demonstration of our society’s failure to provide LGBTQ youths the kind of supportive, accepting environment that they need to feel accepted.

In addition, however, this study also reveals a powerful impact of race in mental health issues among our nation’s youth. Alaska Native and Pacific Islander teens — particularly those who identify as a sexual minority — are nearly 1.5 times as likely as White sexual minorities to self-harm or attempt suicide. Nearly two out of every three Alaska Native and Pacific Islander youths who identify as LGBTQ self-harm. Similarly high rates of sexual ideation and self-harm are seen among multiracial and Hispanic LGBTQ youths.

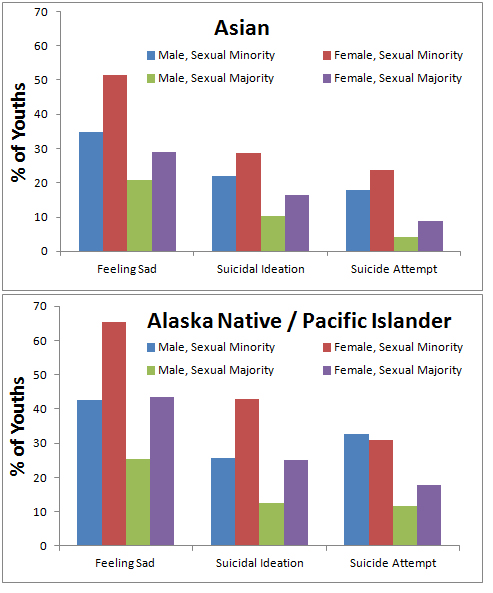

Consistent with the study’s overall findings that mental health outcomes are generally worse for female youths compared to male youths, here is the racial, gender, and sexual break-down for Asian American and Alaska Native / Pacific Islander youths.

The take-home message? Being Asian American or Alaska Native / Pacific Islander, female and LGBTQ appears to negatively impact certain mental health outcomes (although caveat: some of these differences were not found to be statistically significant).

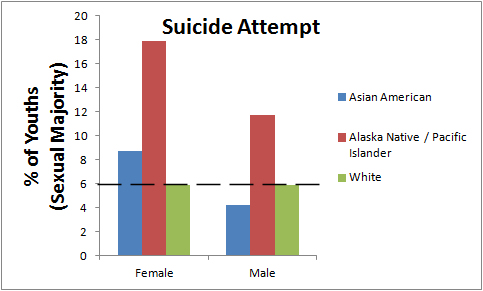

Meanwhile, this study replicates previous findings showing that among straight Asian Americans, depression and suicide attempts are higher than Whites for females (but not males) — a point first presented a few years back but which has been strangely disputed by the academic mental health community. This trend is even more severe among Alaska Native and Pacific Islander youth.

The lower suicide attempt rate among Asian American male youths vs. Whites disappears when considering sexual minorities, but these data may explain why other studies — which have focused predominantly on straight youths and have therefore failed to effectively disaggregate their data for PIs or gay men and women — have routinely reported equal or lower suicide rates for Asian Americans compared to Whites, leading to the myth that mental health concerns are not a significant issue for our community. Clearly, when data are stratified for factors like gender and sexuality, the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities include highly at-risk subpopulations who demand our attention.

Yet, the study also found that for other metrics of mental health — suicidal ideation, for example — some racial and sexual minority groups appear to be protected compared to their White peers. Considering only sexual minorities, for example, Asian and Black females fare better than White females in early “warning signs” of suicide attempts (even though rates of suicide attempts are similar). The authors conclude that an intersectionality framework in considering mental health among minority youths are necessary to fully comprehend the complex cultural and social factors that may influence mental health outcomes (emphasis added):

These patterns accentuate the complexity of multiple, intersecting identities and their interaction with health, health behaviors, and health outcomes. Intersectionality has been suggested as an important conceptual framework through which to understand sexual minority health.15,16 These results affirm that the consequences of possessing multiple marginalized identities are not simply additive (i.e., that “more” marginalization necessarily leads to more negative health outcomes). Rather, it appears that for some health outcomes and behaviors, in particular self-harm, the intersection of minority identities conferred a protective effect; this was the case for sexual minority Asian and Black females compared with their White counterparts.

The authors cite earlier studies pointing at specific cultural taboos towards suicidal planning or self-harm that may protect some minority youth from some manifestations of suicidal thoughts, while not protecting from others.

The authors ultimately conclude that more research must be conducted to stratify “youths of color” with greater detail. They write (emphasis added):

Results of the study point to the limitations of using categories such as “youths of color” when conducting research because salient differences and distinctions among racial/ethnic minorities can be blurred and nullified. This, in turn, has consequences for how we design mental health policies and interventions, for both sexual minority youths and for youths in general. An intersectional lens illuminates the value of tailoring policies and interventions so that they address the unique and particular needs of specific groups.

Indeed.

Here are a few resources for you if you are an Asian American or Pacific Islander who is, or thinks you might be, battling depression and/or other mental health concerns:

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, call:

- 1-800-273-8255 (TALK), 24hr National Suicide Prevention Hotline, >150 languages available

- 1-877-990-8585, 24hr Asian LifeNet Hotline, Cantonese, Mandarin, Japanese, Korean, Fujianese available