As pretty much all of the fandom is aware, Captain America 2 opened in theatres last week to much fanfare. The live-action adaptation of Ed Bruebaker’s acclaimed Winter Soldier storyline had the loins of virtually all fanboys everywhere a-quivering, and nerds of colour hotly anticipated the introduction of Anthony Mackie’s Falcon, who would join the highly-selective ranks of superhero movies’ sidekicks of colour alongside Terrance Howard Don Cheadle’s War Machine and Tadanobu Asano’s Hogun.

As has been made pretty clear in my writing, I’m not a huge fan of Marvel Studios’ superhero movie franchise. I despise the Thor movies with a passion, and am convinced that the success of The Avengers is ruining the superhero movie genre. I’m a Nolanverse girl still looking for someone to make another thinking-man’s comic book movie; and as the years drag on, I’m increasingly convinced I’ll be sorely disappointed until Joseph Gordon-Levitt completes his Sandman adaptation.

Yet, last week, I gamely shelled out my eleven bucks, and went to watch Captain America: The Winter Soldier with Snoopy Jenkins.

And, yes, I walked away with the typical warm-and-fuzzies that come with lots of brainless explosions and high-octane action. And then yes, as soon as the adrenaline wore off a few hours later, I realized how totally and utterly brain-dead that movie was.

Spoilers ahead – please don’t read on unless you’ve watched Winter Soldier

Let me first give credit where credit is due: The Winter Soldier was clearly Marvel Studios’ attempt to make a thinking-man’s superhero movie. With all the auspices of a spy film, Winter Soldier was like a really, really, really dumb version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, where the double-agent turns out to be some absurdly accented suicidal Nazi AI who is housed in the hard-drives of 4,000 Commodore 64s. But, hey, at least Marvel tried. They gave us intrigue, drama, angst, and even a few weak stabs at romance and sexual tension — and then they threw it all away for more explosions and CGI fight scenes.

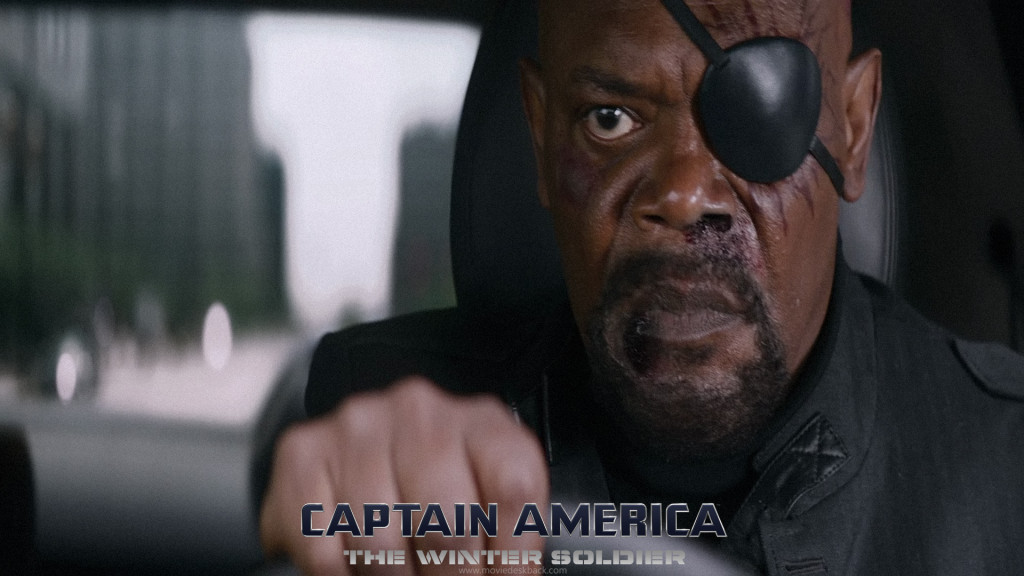

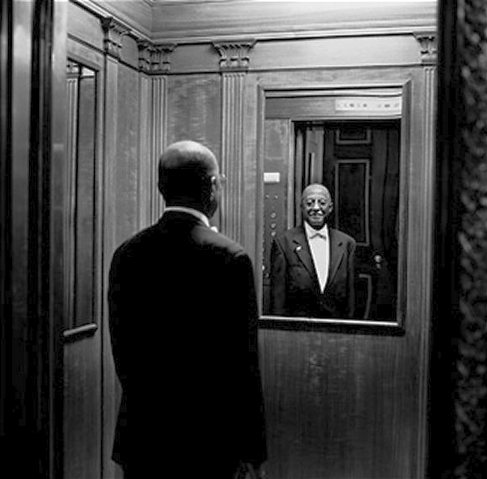

Perhaps the highlight of the film was, for me, the elevator scene. No, not the one where Cap beats the shit out of 30 guys. The first one: the one where Nick Fury invites Cap to ride an elevator with him and then gives his back story. Here, nestled into a superhero movie is perhaps one of the best examples of Marvel Studios adding racial nuance to a character of colour: Fury reminisces about how his grandfather worked as an elevator operator in (presumably) 1920’s or 1930’s New York City, and then walked home with his tips in his lunch bag along with a .22 handgun. The scene works on a few levels. On the surface, it introduces Fury’s near-universal distrust of everyone around him, a distrust that features later in the film.

But, reading slightly between the lines, Fury’s distrust of others becomes a racialized behaviour: a justifiably learned reaction from a patriarch who grew up in the segregated North; who works one of the best jobs available to Black men at the time; who nonetheless still works in the service industry in proximity to, but never a part of, the White man’s world; who walks home from the wealth of Wall Street to one of several all-Black enclaves in the city; whom we could imagine maybe even living in Harlem during the height of the Harlem Renaissance, only to watch the neighbourhood deteriorate in the subsequent decades due to redlining and other damning forms of economic violence enacted against Blacks during this era.

Nick Fury never says the word Black, and never makes mention of any of this history — yet, his Blackness informs his distrust of the world in a way that feels realistic and whole. Later, Fury’s Blackness is again invoked during the scene where he is subjected to the World’s Worst Stop-and-Frisk Stop Ever.

These brief moments of subversive racial invocation are, and should be, the template for comic book diversity — the desired middle-ground between the overt stereotyping of superheroes of colour we’ve seen in the past that would define every minority character by his or her race alone, and the ridiculous post-racial fantasy advocated by some that would leave race a meaningless costume detail.

Yet, while I think the sophisticated treatment of Nick Fury’s race in The Winter Soldier is the film’s major strength, I also think it also highlights the film’s chief weakness: the apparent wariness Marvel Studios has in fully tackling uncomfortable complexity in its storylines. In the same scene where Nick Fury recounts his grandfather’s life as an elevator operator in 1920’s and 1930’s New York City, the film deliberately stops short from reminding Cap, Nick Fury or the viewer that the segregated America of Nick Fury’s grandfather is also Steve Rogers’ America.

And so it goes with the whole of The Winter Soldier: in the same film that introduces Nick Fury as a distinctly racialized up-by-my-bootstraps executive with one foot still firmly planted in Black America’s segregated past, and in the same film that introduces the gamely loyal Falcon who is about a stone’s throw from being Steve Rogers’ manservant, yet also clearly smart enough to know it; Marvel flatly refuses to let Captain America (or Steve Rogers) explore his own racial baggage. The viewer is treated to two wildly different depictions of Black male America including one who invokes the racial history of 1920’s segregated America, yet we are expected to simultaneously believe that Steve Rogers, who grew up in that segregated America, has no commentary on this whatsoever?

Instead, we are expected to believe that Steve Rogers, who came-of-age in a world where Black men as elevator operators and stevedores was both commonplace and expected, has no issue taking orders from a Black man serving as his superior? We are expected to believe that Steve Rogers, who enrolled in the military prior to racial integration, has no concerns about calling a Black man his wingman? We are expected to believe that a man who grew up in 1920’s White America will not find it mildly shocking that the culture of the intervening years since his hibernation was defined predominantly by Black musicians?

And so, The Winter Soldier displays an exceptional cowardice: in multiple instances, the film dips a toe into a muddy grey area of racial politics, but then flees back to the shallow waters of post-racial fantasy amidst low-brow explosions and a girl doing backflips when the grime threatens to dirty the image of its protagonist, Captain America. I do not assert that Steve Rogers should be a flaming racist; but the complete absence of culture shock he exhibits in racially integrated 21st century America is disconcerting. How this man could have missed the entirety of the Civil Rights Movement with no lasting consequences is the single primary conceit of the Captain America movies … and one that deserves to be corrected or addressed at some point.

So, too does The Winter Soldier mess up its major storyline regarding government spying and geopolitical threats. While the film attempts to incorporate the standard government spying vs. Edward Snowden freedom of information storyline we’ve now seen repeated ad nauseum in multiple films over the last year and a half, The Winter Soldier set a complex political stage, but then abandons it mid-movie in favour of cheap explosions and high death counts. Rather than to discuss the necessity of a covert federal agency like S.H.I.E.L.D. in a globalized world where, apparently, Nazis lurk around every corner, the film makes a few faint stabs at the power of the helicarrier technology to do good, only to assert within 20 minutes that it’s a clear example of government overreach. By the second half of the movie, there is no doubt in the mind of any viewer that the triple helicarriers have got to go.

And why? Because Captain America said so.

That’s right, folks. Rather than invoke the uniquely American system of checks and balances to create a system of government oversight in the use of the helicarrier technology (which, let’s face it, is a powerful tool that could be used to establish world peace), Captain America casts himself as judge, jury and executioner when it comes to the US federal government’s entire intelligence apparatus. Captain America in The Winter Soldier takes it upon himself to circumvent the explicit will of America’s elected officials — which, lest we forget, approved of the helicarrier project at every stage of its formation. Instead, Cap decides to singlehandedly alter the course of America’s political future. When Captain America and Nick Fury discover that S.H.I.E.L.D. has been infiltrated by H.Y.D.R.A., their solution is to blow S.H.I.E.L.D. up.

The film has no room for discussion of how Captain America’s decision to take up arms against the Marvel Universe’s version of the C.I.A. is clearly treasonous. They don’t talk about how Cap, Black Widow, and Falcon took it upon themselves to steal top-secret Falcon technology from the U.S. Army, which they then used against American citizens. They don’t discuss the aftermath of releasing S.H.I.E.L.D. state secrets to the international community, and how this could empower and embolden America’s foreign enemies. They don’t discuss how their plan to replace the helicarrier targeting chips to cause project-wide self-destruction resulted in the waste of trillions of taxpayer dollars, along with the implosion of the entire industrial complex that otherwise would have centred around maintenance of these hovercrafts. And, worse yet, our stalwart heroes seem unperturbed by the fact that H.Y.D.R.A. has only infiltrated an unknown subset of S.H.I.E.L.D.; instead, all S.H.I.E.L.D. personnel who man the helicarriers are targeted by our “heroes” for destruction.

“How will we know who the bad guys are?” asks Falcon at one point.

“They’ll be the ones shooting at us!” quips Cap. Of course, they wouldn’t be shooting at Cap and his manservant sidekick wingman because they just declared war on an American intelligence agency.

And, when the helicarriers go down in flames, the people who died weren’t H.Y.D.R.A. agents; they were predominantly the hundreds or thousands of support staff whose only crime might have been that they were hired to mop floors on decks 29-35 of Helicarrier #2 on that fateful day.

Captain America, Black Widow and Falcon weren’t American heroes in The Winter Soldier. They were domestic terrorists.

And, perhaps their actions were just. Perhaps, under different circumstances that maybe involved some sort of Congressional approval, Cap and company would have pursued the same final solution. The problem is that the film never interrogated that. Cap et al. just skipped all the boring discussion over the morality and ethics of their actions, and went straight to the blowing shit up.

At the end of the day, we are left with the vaguely smug feeling that Captain America once again was on the side of the righteous, and now he’s got a new friend with a super-lame power (yes, I said it — Falcon is super-lame) to go fight Nazis with. Never mind that he basically committed a military coup of America’s intelligence community.

So yet again, as with all Marvel Studios films, we were left with yet another flashy, explosion-filled testosterone-fest, that offers high-flying action and cheap thrills at the expense of intelligent story-telling. Screenwriters shirked away from the opportunity to dissect the mythos — and pathos — of America’s Greatest Generation in favour of yet another cardboard cut-out of a superhero doing superhero things that are as beautiful as they are substanceless. The movie further fails to give Falcon sufficient humanity to push back against the film’s repeated ham-fisted, white supremacist insistence that this proud African-American sidekick is inferior to Steve Rogers in every way; a point that actually underlies the visual sight gag that opens the film. And, yes, the eponymous Winter Soldier — and all that he represents in the Captain America canon — is completely wasted.

In short, if you wanted explosions and high body count, The Winter Soldier is definitely the movie for you. But, when that theatre darkens and you get reminded to please silence your cellphones, don’t forget to turn your brain off as well.