Carol is a divisive character in The Walking Dead fandom.

Some find Carol’s multi-season metamorphosis clunky, her decisions suffering from a failure of adequate exposition, and her current persona frustratingly rigid. During Season Two, these critics were confused by the blame she placed on her fellow survivors in her daughter’s disappearance, and were flummoxed the juxtaposition of this fear for her daughter’s safety with an otherwise passivity when it came to life in the post-zombie apocalypse. For the entire series prior to their arrival at the Prison, Carol could be reasonably characterized as survivor dead weight, obstinately satisfied to perform domestic chores over learning to wield a rifle. To these critical Carol-haters, her whiplash-fast transformation at the start of Season 4 was jarring.

Others view Carol as a feminist icon, a necessary counter-point to the passivity and helplessness of Lori. The Female Gaze cites Carol’s development of female agency in her appreciation of the character:

One of the most powerful characters on The Walking Dead is Carol, a survivor of domestic violence who starts off meek and unsure of herself. … She doesn’t only grow inner strength after finally escaping her abusive husband and watching her own daughter turn into a zombie; she also brings the ostracized Daryl into the foray [sic] of Rick’s group, and later asks him if he wants to fool around on top of a bus!

Twitter fans of The Walking Dead routinely cite Carol’s leadership position in the Prison and her clear willingness to defy Rick and the other male survivors in their appreciation of the character. And certainly, by the start of Season 4, Carol has left far behind the woman she was in Season One to become the steadfast pragmatist, capable of moments of both efficient violence and tender nurturing, and above all unwavering in her personal convictions.

And why? Unlike in the comic where Carol fades almost immediately into the background, in the AMC show, Carol has assumed a far more critical role: Carol is the anti-Hershel.

Spoilers ahead! Please be wary!

The Walking Dead is not really about zombies. The Walkers are incidental, mere plot devices to make possible actions — thievery, murder, and cannibalism — that would be otherwise unthinkable in a civilized world. The Walking Dead uses zombies as a backdrop through which to explore human morality and ethics. The constant threat of death might be presumed to remove choice, but in fact The Walking Dead asserts that it is under these conditions that choice becomes most precious.

The notion that these choices are at the very essence of who each survivor is manifests in the Three Questions that must be answered to earn entry into Rick group: How many Walkers have you killed? How many people have you killed? And why? As Hershel says in episode 5 of Season 4, “Every moment now, you don’t have a choice. The only thing you can choose is what you’re risking it for.”

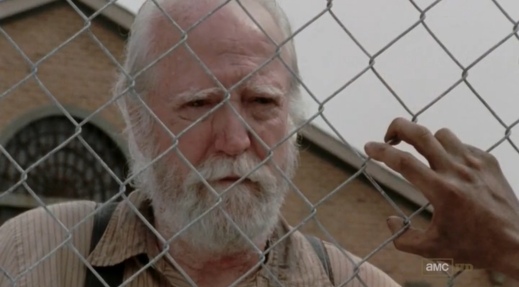

Likely due to his survival of the Walker attack early in Season 3 that claimed his leg, Hershel has come to recognize that post-apocalyptic life for all of the survivors is just borrowed time. He, unique among the survivors, had accepted the fact of his own mortality. He understood: “You step outside, you risk your life. you take a drink of water, you risk your life. And nowadays you breathe and you risk your life”.

But, he also finds within this realization a higher purpose: to foster and protect those things that make us human. In a world where every action could lead to an immediate, graceless death, Hershel doesn’t value survival; he covets moments of tenderness, of innocence, of selflessness, of humanity — even if, or particularly when, it comes at great personal risk. This is why he risks his health to care for the quarantined, why he wheels heavy corpses down a flight of stairs away from the living and covers their faces before stabbing them in the head, why he refuses to shoot a Walker in front of a terrified Lizzy and Mika. At the moment of his death, Hershel enigmatically smiles: and we wonder if it is because he is reflecting on his own humanity well-expressed.

Against Hershel, Carol is an exercise in contrast. For the first three seasons, Carol relied upon other survivors to protect her. First, it is through the emotional support of the other survivors that Carol escapes her abusive husband. In Season Three, Carol spends several harrowing days trapped in a closet, having witnessed T-Dog sacrifice his life to preserve hers.

Upon her rescue, Carol must cope with two recent deaths: not only did her daughter die because she was too young to protect herself, but Carol’s own physical weakness led to the death of a fellow survivor and friend. Thus, Carol has come to believe that the protection of one’s life is an ends that justifies any means.

Whereas Hershel prized humanity even at the cost of human life, Carol values human life over humanity.

And, the unique world of The Walking Dead allows us to explore just how high a price Carol pays for her code of ethics.

This past Sunday’s Season Four episode, “The Grove”, challenges the lengths to which Carol will place survival over humanity, and in so doing raises several ethical questions. The episode answers several lingering questions since the start of Season Four, chief among them that Lizzie, the orphaned older daughter of a former Prison resident, is far more troubled then anyone had imagined.

As was established in the first episode of Season Four, Lizzie does not perceive Walkers as a threat; instead, she views them as transformed humans to be cared for, or pets to be played with. At the Prison, she and her sister Mika named fence Walkers and visited them every day. In “The Grove”, it is revealed that the two girls also trapped rodents and fed them to the fence Walkers, contributing to the eventual fall of the outer perimeter.

But only in “The Grove” do we fully understand that Lizzie isn’t just mildly traumatized by the zombie apocalypse, but rather her delusions appear to be a manifestation of a pre-existing schizophrenia. The depth of Lizzie’s mental illness as well as the remarkable child-like innocence it confers upon her is established from the onset; the episode opens with Lizzie “playing tag” with a Walker who is clearly trying to eat her, and later shows Lizzie screaming “how would you like it if I kill you?” when Carol quickly runs out to dispatch it. During a panic attack brought on by Mika shooting a Walker before Lizzie’s eyes, Lizzie starts to hyperventilate, and Mika tells Lizzie that she knows she’s supposed to “look at the flowers” when these kinds of attacks happen. That Lizzie has a routine for dealing with these kinds of attacks, and that it is a routine that has also been ingrained into Mika, suggest that Lizzie is bonafide mentally ill and has struggled with it for a long time. Whereas viewers were previously led to believe that Lizzie simply refused to accept the zombie reality, it becomes clear over the course of “The Grove” that Lizzie can’t; Lizzie isn’t stupid, she is sick.

Lizzie appears to be suffering from a form of schizophrenia, one that leads her into the delusion that death is merely an inevitable transformation into zombification as a different state of being. And worse still, she appears to be deteriorating rapidly in this delusion. Traumatized by the violence of having to shoot several Walkers, Lizzie appears to arrive at the conclusion that she most facilitate the peaceful transformation of all the survivors into Walkers. Left alone with her sister and with baby Judith, Lizzie stabs Mika to death but protects Mika’s brain, so that she can return as a Walker. She sees this as both an inevitability for all the survivors, as well as a mercy for her sister, and doesn’t understand the finality of her actions.

Horrified, Carol and Tyreese must consider their options. Could they stay together and get Lizzie to Terminus? Could they split up? Eventually, they come to an unspoken consensus. Carol takes Lizzie out into the garden and executes her, in a scene reminiscent of what happened to Old Yeller.

We understand Carol’s logic, and her reasons. Lizzie is not just a liability, she has become a threat to the group’s personal safety. The solution that most guarantees the protection of human life — that of Carol’s, Tyreese’s, and Judith’s — was the death of one individual. The needs of the many outweighed the needs of the one sick child.

But there’s a reason why the Kobayashi Maru is a no-win situation.

If Lizzie lived in our world, punishing her for her actions would be unthinkable: Lizzie is a mentally ill minor who was beyond any possible understanding of right from wrong. Lizzie is an innocent child, one who even at the moment of her impending death is not focused on what she has done to her sister but on the prospect that she has disappointed Carol, her mother figure. Lizzie dies never comprehending what she has done wrong.

Lizzie’s killing is not, and is not presented as, capital punishment for the crime of murder. Like Karen and the other one, Lizzie is euthanized not for what she has done, but to prevent what she might do. She is murdered because her life — the life of a mentally ill child — wasn’t worth the risk of keeping her alive.

Thus, we are forced to ask ourselves: was killing Lizzie moral, ethical, or just? Was Carol, Tyreese and Judith’s life worth more than Lizzie’s?

The fact remains that — as Hershel might have argued had he been alive to do so — even in the apparent absence of choice, all that Carol and Tyreese had left was the most essential, most human of all choices: what were they willing to risk their lives for? In a world where the mere acts that sustain life are innately an assumed risk, all they had left was to decide how they would risk their lives.

As with Karen and the other one, the risk could have been minimized — Lizzie could have been immobilized and watched over in the same way that Karen was quarantined away from the rest of the Prison to limit the chances of transmission, and in the same way that Carol and Tyreese now care for Judith — but still protected. Instead, Carol acts as judge, jury and executioner, deciding that Lizzie, Karen and the other one (but notably not Judith) are too much of a liability to keep alive.

With Lizzie, one might argue that her condition was incurable. But Carol’s decision to kill Lizzie exists in a context wherein Carol has made a choice long ago about the value of human life that threatens her own. Carol has already gone down a path that justifies the killing of the innocent; thus, Lizzie’s death in Sunday night’s episode was a foregone conclusion.

The deaths of Karen and the other one is equally, if not more, senseless then Lizzie’s: in that first incident, there was no guarantee that the flu was fatal to everyone, and moreover, Carol chose to kill them after they were already quarantined; either the quarantine would work, or it wouldn’t. But even if the illness was both fatal and transmissable, the rest of the Prison was already exposed through the time that Karen and the other one had spent interacting with the rest of the community prior to quarantine; their deaths did not meaningfully improve the odds of survival for the rest of the Community, and were carried out under the assumption that Karen and the other one would not recover on their own, or that Hershel wouldn’t have stumbled upon the elderberry solution sooner. In essence, Carol decides Karen and the other one’s lives aren’t worth the gamble that they don’t pose any serious risk, and executes them for the dubious “crime” of being unlucky enough to fall ill.

In short, Carol’s code advocates the culling of the weak, while Hershel’s code defends them. Hershel would argue that assuming the risk of caring for those who cannot care for themselves, even at great personal risk, is the ethical and humane thing to do: that human life in the absence of humanity is not worth living.

And, Hershel would not have been wrong.

There is a reason why in a non-zombie civilized society, we do not execute people whom we find inculpable for their criminal acts. There is a reason why we don’t punish people for crimes they have not yet committed, even while that assumes the added societal risk that they might do just that. There is a reason why we don’t advocate the “humane” execution of the physically and mentally disabled to avoid the burden of care. There is a reason why we argue the protection of civil liberties outweighs the personal risk of a terrorist attack. In a civilized world, we understand that being alive is alone insufficient. In a civilized world, we prize not just human life, but those things that add value to human life.

Should the same not be true in a world without civilization?

Carol’s code — that places base survival over humanity — is no different from that of a Walker (should he be able to articulate a moral code): the zombie’s entire existence depends upon the carnivorous rending of human flesh to sustain the undying appearance of life. The zombie’s hunger warrants his violence.

Carol will do whatever it takes to keep herself alive because she believes the ends — survival — justify the means — murder. And she follows this code even if it means transforming into the exact monster she fears.

Perhaps Lizzie wasn’t really so deluded after all.