Despite the precepts of the Model Minority Myth, not all Asian American & Pacific Islanders (AAPI) in the United States arrived as wealthy, middle-class East Asian entrepreneurs to pursue graduate degrees or to start small businesses. According to statistics published yesterday by the Center for American Progress, one-fifth of AAPI who received permanent resident status in 2012 did so as refugees or asylees; yet this population — many of whom can trace their ethnic heritage to Southeast Asia — struggles for visibility against the backdrop of the larger AAPI community. This invisibility is exacerbated by the absence of disaggregated data for the AAPI community along ethnic lines, which can reveal the unique sociopolitical iniquities that plague Southeast Asian Americans.

According to the United Nations, America is home to approximately 70,000 Bhutanese Americans, representing less than 0.5% of the AAPI population. Bhutanese Americans are ethnically derived from the small land-locked country of Bhutan, a small country in the Himalayas bordered by the two much larger nations of China and India. In the 1980’s, thousands of Bhutanese were forced out of Bhutan during a period of countrywide political turmoil (many expelled Bhutanese were targeted due to their non-Tibetan origins), and were forced to relocate to temporary refugee camps in the neighbouring country of Nepal; some subsequently accepted permanent relocation to the United States as political refugees starting in 2008.

Currently, the Bhutanese American population is concentrated in several states including Texas, Arizona, and New York. In New Hampshire, the state’s population of 2000 Bhutanese Americans represent 65% of the state’s total refugee population.

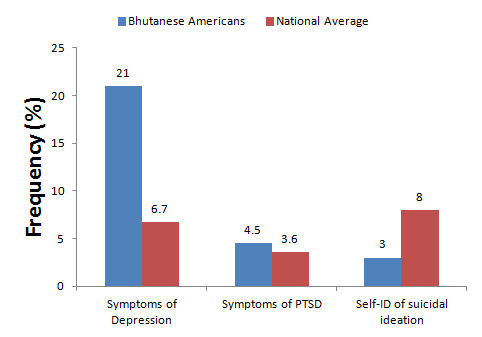

And shockingly, our country’s small, young, and underserved population of Bhutanese American refugees suffer among the country’s highest rates of PTSD, depression, and suicide — the latter of which is nearly twice that of national suicide rates — indicating a clear failure of America’s existing healthcare and social services programs to adequately address and support Bhutanese Americans.

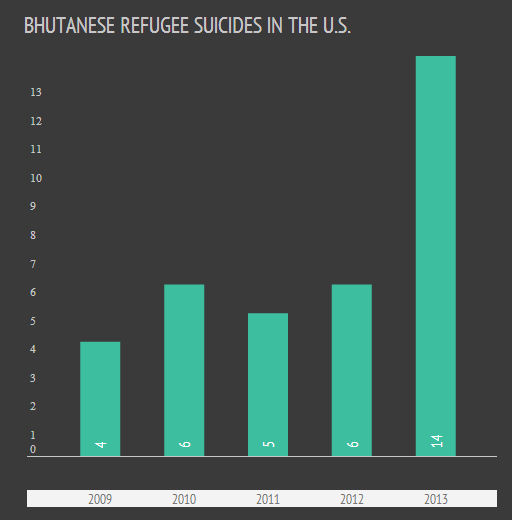

Last year, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued a report specifically examining the suicide rate among Bhutanese Americans. They discovered 16 reported suicides — spanning 10 states — of Bhutanese American refugees in the three years between 2009 and 2012, which translates into a startling suicide rate of 20.4 deaths per 100,000. By comparison, the national suicide rate in America is 11.5 deaths per 100,000.

In other words, the suicide rate for Bhutanese Americans is nearly double that of the national average, and is the highest reported suicide rate of any refugee population in the United States.

This suicide rate far exceeds that of even the AAPI population, including AAPI women who according to the work of Dr. Eliza Noh, experience the greatest suicide rate among all women. In Dr. Noh’s work, the suicide rate of AAPI women was 6.5 per 100,000 compared to the rate of age- and geographically-matched White women (4.5 per 100,000).

Further, the suicide rate for Bhutanese Americans may be underreported. In 2013, 14 suicides of Bhutanese Americans was reported to the CDC, a number nearly equal to the number of suicides observed within this population in the prior three years.

Suicide within the Bhutanese American community also deviates sharply from the typical dogma regarding suicide in the national population: based on psychological autopsies conducted by CDC investigators on reported suicide victims, Bhutanese Americans who commit suicide are predominantly male, married, and with a median age of 34. This is in sharp contrast to national statistics in America that show that in the general population, the populations at highest risk for suicide are either single college-aged males, or the elderly.

The question remains, of course: why is the suicide rate among Bhutanese Americans unusually high? NPR, which reported on this study earlier this year, pulls a quote from study author Dr. Sharmila Shetty, which seems to imply that the rate is high in part due to the lack of religious and cultural taboos in Hindu and Buddhist religions against death by suicide. It is true that most Bhutanese Americans are of the Hindu faith. However, NPR’s choice to focus on this quote seems abnormally simplistic, culturally insensitive, marginally Orientalist, and fails to remotely represent the nuanced discussion that Shetty and other study authors presented in their study.

Of greater relevance, I think, is the CDC’s findings in their national phone survey of over 500 Bhutanese Americans. Among survey respondents, the CDC found that roughly 1 in 5 experienced symptoms of depression, and nearly 5% suffered symptoms of PTSD; all this occurred despite a far below-average self-reporting of suicidal ideation suggesting cultural stigma against identifying or reporting these symptoms.

These data strongly imply that the suicide rate has less to do with a cultural acceptance suicide. Instead, the high suicide likely arises as a complex combination of the high stressors associated with the refugee experience, and inadequate outreach by and access to mental health resources for Bhutanese Americans. Indeed, the CDC reports that in their psychological autopsies of the 16 cases of Bhutanese American suicides in 2009-2012, most of the suicide victims were unemployed or underemployed. Most of the victims cited their primary stresses as related to the loss of country, citizenship, and personal belongings, as well as language barriers in the United States.

Existing studies have already identified exceptionally high incidence of PTSD among Hmong Americans, Vietnamese Americans, Laotian Americans, Cambodian Americans and other Southeast Asian American communities. In one study (separate from the Bhutanese American summarized above), as many as 70% of Southeast Asian refugees living overseas exhibited signs of PTSD. In another study that surveyed Hmong, Laotian, Cambodian and Vietnamese American refugees, as many as 73% suffered major depression and 14% had PTSD (reviewed here). Additional studies have further identified many other specific areas where America underserves these Southeast Asian American refugee populations. This review by Song E. Lee (available in full text through the Hmong Virtual Library) synthesizes decades of mental health research to provide a comprehensive overview of the high incidence of depression, anxiety, and PTSD among Hmong Americans; Bhutanese Americans, although having only been in America for just over five years, likely face many of these same challenges.

In addition, few mental health resources are available for Asian American; even fewer for Southeast Asians. In the 1990’s, only 70 Asian American mental health professionals were available for every 100,000 Asian Americans — a rate that was roughly half that of Whites; the availability of Southeast Asian American mental health professionals is likely to be significantly lower. Between one-half to two-thirds of Hmong, Laotian and Cambodian Americans are linguistically isolated, further emphasizing the need for multilingual Asian American mental health providers to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment of mental and anxiety disorders. In addition, high poverty rates within many Southeast Asian American populations limit healthcare coverage. Data for Vietnamese Americans, one of the nation’s largest Southeast Asian American populations that includes many who arrived under refugee status, show that nearly one-fourth lack access to healthcare, which prevents early diagnosis and treatment of clinical depression, necessary for suicide prevention. Whether as a consequence of this lack of access, or exacerbated by cultural stigma, Asian Americans regardless of ethnicity are the least likely of any racial or ethnic group to report symptoms of a mood or anxiety disorder to a health professional, and those that do tend to wait longer until symptoms are more extreme; both factors contribute to the high rates of depression and suicide in the Asian American community.

Although many non-profits have been established to ease the transition for Southeast Asian refugees — many of these organizations facilitate access for refugees to healthcare and mental health resources — one report showed that only 0.07% of federal and state funds go to Asian American organizations, and roughly half of that money go to support arts and culture. Consequently, NGOs that exist to combat the effects of poverty and under-education among Asian Americans, including those in place for newly-immigrated refugees, struggle to keep their doors open with nearly non-existent funding.

The second and more important question is this: why aren’t we talking about this? Regular readers of this blog know that Asian American mental health awareness is an issue of primary importance to me. I am embarrassed to say that while I was aware that incidence of depression, PTSD, and suicide were higher in Asian American refugee populations, I was shocked to find that the suicide rate for Bhutanese Americans was twice that of the national average, and that it could be similarly high among other Asian American refugee communities. I am mortified and furious that the mental health challenges — as well as problems arising from poverty and limited access to higher education — faced by our Southeast Asian American communities goes largely unaddressed when talking about Asian American mental health, even among Asian Americans; and yes, too often, I am part of this problem.

Asian American mental health has always been an emotional issue for me in part because I see so many deaths as preventable; with more education, more awareness, more attention, more data, more dialogue, more love and support, more language- and culture-specific resources, and most importantly more advocacy, so many people struggling in the shadows with depression could be brought out of the shadows to receive the treatment they desperately need. The strength it takes to arrive in America as a refugee is impossible for many of us to understand; Bhutanese Americans should not have to continue to fight for basic survival after having landed in America. They, like many Asian Americans (particularly many other Southeast Asian Americans) who arrived here as refugees and asylees, deserve our community’s help; not our silence.

If you or someone you know are struggling with severe depression or suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevent Hotline at 1-800-273-TALK or the Asian LifeNet Hotline at 1-877-990-8585. Two of the nation’s largest non-profit organizations focused on Asian American mental health are AASPE and NAAPIMHA.