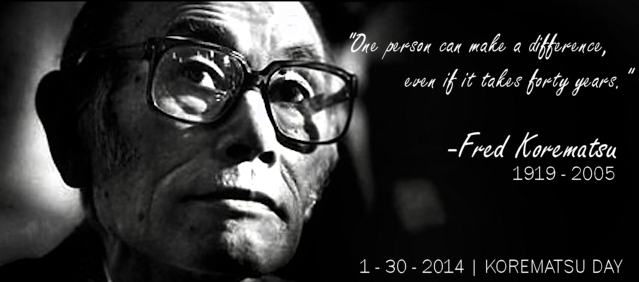

Today would have been Fred Korematsu‘s 95th birthday.

Born on January 30, 1919 in Oakland, California to Japanese parents, Fred Korematsu pursued all the trappings of a typical American childhood. He attended public school, participated in the tennis and swim teams, and was conscripted to military service under the 1940 Selective Training and Service Act, which was passed by Congress to boost America’s military defenses in the face of the growing threats of World War II. Although he was rejected by the US Navy due to stomach ulcers, Korematsu was inspired to try and serve his country however possible and sought jobs as a welder at the local shipyard in order to help build American warships. In short, Fred Korematsu was a proud American citizen and a patriot.

Unfortunately, for most of his life, America treated him like a criminal, based solely on his race.

America of the 1940’s was a country of institutionalized and implicit racial segregation. Jim Crow laws were thriving in the South, and in California, casual intolerance of non-Whites was the norm. Throughout the country, foreign-born non-Whites — including Fred Korematsu’s parents — were still denied the right to naturalize, and even Japanese American citizens born on U.S. soil were treated with fear, suspicion, and outright hatred.

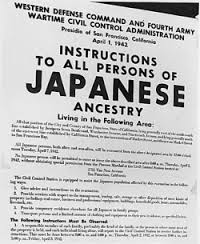

That seething undercurrent of anti-Japanese intolerance was whipped into a frenzy with Japan’s unannounced attack on Pearl Harbor, which claimed the lives of nearly 2500 American servicemen. Following Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II, Japanese Americans were regarded with open hostility under the misguided belief that they were Japanese spies. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, unilaterally granting authority to the Secretary of War to designate certain areas of the country military areas and paving the way for one of the largest violations of American constitutional rights in this nation’s history.

In the wake of Executive Order 9066, 120,000 Japanese Americans of all ages — including roughly 80,000 US-born citizens — were subjected to curfews and other restrictions, and eventually forcibly relocated to mass prison camps, some no more than a collection of tents or sheds hastily-erected in the country’s harshest and most isolated environments behind barbed wire and under the careful guard of men armed with machine guns. In many camps, there was no heat, no running water, no privacy, and even insufficient toilets or showers. Internees were imprisoned in the camps without trial based solely on the fact of their racial and ethnic identities and forced to live under strict military control for years; this ugly episode of American history has been referred to as America’s “concentration camps”. Write the Japanese American National Museum and the American Jewish Committee in a joint statement in 1988 (from Wikipedia):

A concentration camp is a place where people are imprisoned not because of any crimes they have committed, but simply because of who they are. Although many groups have been singled out for such persecution throughout history, the term ‘concentration camp’ was first used at the turn of the [20th] century in the Spanish American and Boer Wars. During World War II, America’s concentration camps were clearly distinguishable from Nazi Germany’s. Nazi camps were places of torture, barbarous medical experiments and summary executions; some were extermination centers with gas chambers. Six million Jews were slaughtered in the Holocaust. Many others, including Gypsies, Poles, homosexuals and political dissidents were also victims of the Nazi concentration camps. In recent years, concentration camps have existed in the former Soviet Union, Cambodiaand Bosnia. Despite differences, all had one thing in common: the people in power removed a minority group from the general population and the rest of society let it happen.

But, the myth of universal Japanese American acquiescence to internment is just that: a myth. The most notable — but hardly the only — example of Japanese American defiance to the unconstitutional internment of American citizens was Fred Korematsu’s refusal to comply to relocation orders.

In May of 1942, Japanese Americans throughout parts of the West Coast were ordered to report en masse to assembly centres prior to internment; Fred Korematsu refused. He never reported for internment.

He was arrested later that month and charged with violating military relocation orders. While in jail, Korematsu partnered with the ACLU to issue one of the first legal challenges to Japanese American relocation and internment, but courts upheld the government’s position. Korematsu was subsequently transported to Tanforan Assembly Centre, converted racetrack, where he and his family was assigned to live in a refurbished horse stall, before being again relocated to the internment camp in Topaz, Utah. From the internment camps, Korematsu appealed his case in the landmark Korematsu v United States 1944 Supreme Court case which again upheld the constitutionality of internment, arguing that the government’s “need” to protect against espionage outweighed the individual rights of Japanese American citizens.

The end of World War II marked Korematsu’s release from the Topaz internment camp, but it also marked the nearly fifty year struggle to seek redress from the U.S. government for its unprecedented forcible relocation of Japanese American citizens; an act that for most is in clear and obvious violation of the very principles that this country was founded upon. That advocacy work centered largely around Korematsu’s federal conviction for defying Executive Order 9066, and the subsequent United States v. Korematsu case.

The nearly fifty years of persistent, tireless community advocacy by Asian American activists culminated in Korematsu’s federal charge being overturned in 1983, after he filed for a writ of coram nobis. Five years later, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 — a bill co-sponsored by former internee and House Representative Norm Mineta — which granted $20,000 in reparations to all living survivors of the internment camps.

But, notably, the United States has never ruled Japanese American internment unconstitutional, and the legal threat of the U.S. government resorting to forcible relocation of its citizens under guise of military safety remains to this day.

In 2010, six years after Korematsu’s death, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger declared January 30th official Korematsu Day in California after years of advocacy by the Korematsu Institute, a non-profit centre dedicated to preserving and protecting Korematsu’s history and legacy.

Korematsu Day is a day to commemorate Fred Korematsu’s lifelong struggle to challenge the constitutionality of Japanese American internment and seek redress for all internees. It is a day to celebrate the courage it takes to defy your country out of love and respect for its founding principles, and to demand action when your country strays from these essentials.

Today, I remember Fred Korematsu’s fight for justice for Japanese American internees, as well as the other Japanese Americans who fought against forcible relocation: Gordon Hirabayashi, whose parallel case challenged the constitutionality of curfews imposed against Japanese American citizens; Mitsuye Endo, whose landmark Supreme Court case decided on the same day as Korematsu’s established that the government did not have a right to continue to detain internees who had proven themselves loyal; Norm Mineta, whose work in Congress helped bring redress to internees; George Takei, whose dedication to bringing popular awareness to this country’s history of internment is undeniable; the hundreds of nameless No-No boys, who defied the US government by responding “no” to the loyalty questions distributed to internees in the 1943 Leave Clearance Application Form; the thousands of internees, who found the courage to commit large and small daily acts of resistance — most of them unrecorded and lost to history — within the internment camps; and, the thousands of community activists including the members of the Korematsu Isntitute, who have worked over the last 70 years since the closing of the internment camps so that America never forgets this terrible moment in its history.

Fred Korematsu Day also challenges us to never forget how the U.S. government violated its citizens in the name of military safety. It is a reminder of our shared responsibility to protect and fight for our civil liberties, liberties that even today are still under constant attack. Korematsu Day is a promise that we all have within us that same courage to defy our country in defense of the civil rights of its citizenry, and an encouragement to find ways to exercise it. Korematsu Day is a day to renew our resolve that we will never permit a citizen’s constitutional rights to be violated quietly.

So please join me today in remembering the incredible legacy of Fred Korematsu and the many other civil rights advocates who came before us, and to honour their memory by taking up their torch in the struggle to defend civil liberties and civil rights today.

Act Now! There are many fabulous Asian American non-profit organizations out there, including ones aimed at protecting the civil liberties of Asian American citizens. They could always use donation of your time or money.

Also, please share this post to help spread the history of Fred Korematsu and Japanese American internment.