We’re going in on Day 5 of #NotYourAsianSidekick, the hash-tag that blew up the Twitterverse with a conversation on Asian American race identity and feminism. And, boy, has it sparked online and offline conversation. Hash-tag founder Suey Park (@suey_park) has joined forces with 18millionrising (@18millionrising) to schedule appearances on several mainstream media outlets talking Asian American feminism — which is remarkable visibility for the Asian American feminist community. Meanwhile, several established Asian American writers have offered their comments in the pages of Time Magazine and the Wall Street Journal. And as of this writing, #NotYourAsianSidekick is still going strong with new tweets being published every few minutes; further, NotYourAsianSidekick.com was launched this week (now with free stickers!).

But, of course, the question on everyone‘s mind is: what’s next?

Kai Ma (@kai_ma), former editor-in-chief of KoreAm, insightfully considers this question in her Time magazine opinion piece. While noting that #NotYourAsianSidekick has picked up on ideas first postulated by such community giants as Yuri Kochiyama, Grace Lee Boggs, and Mari Matsuda, Ma cites the immediate and transient nature of Twitter to write:

It’s true that the multiple movements of decades past — which included feminists, civil rights activists and Asian-American activism — left behind some issues that perhaps led to this place, where a group of mostly younger Asian-American women have found a moment of remarkable solidarity in 140 words or less. But it is also fitting that according to its website, #NotYourAsianSidekick has plans to take this beyond Twitter. It has to. An ephemeral platform like the Internet — though it may feel cathartic — is not always terribly productive.

But, others have questioned whether a Twitter conversation can launch a social movement — something focused, structured, organised, and capable of enacting social change. How can it, we wonder, when Twitter suffers the aforementioned 140-character limit, and if most Tweets disappear from one’s feed after minutes or hours? How can it, others wonder, when they feel Twitter is a noxious, sexist, intellectually lazy and oversimplified place?

To answer this question, I think it’s important to first understand the novelty of #NotYourAsianSidekick. And to understand this, I think it’s important to recognize one important fact: you may be too old to get this.

Now, before you claim I’m being ageist, let me clarify: I’m also too old to get this too.

I’m 31 years old, and self-identify as a Gen Y-er. I am not married, don’t have kids, and am really just starting my professional career. I am, by most definitions, a “young adult” (especially if you go by the mantra that 30 is the new 20).

That being said, I remember what a dial-up modem sounds like. I used to view and edit my blog using Netscape Navigator. I remember when Facebook was launched (and how you had to get an invite from people, and how I refused to get an account for years). I remember when you used to make websites on Geocities and blog on Blogger.

I got on Twitter less than 5 years ago. I’m still not a natural Tweeter (Tweep? Twerp? Whatever?).I find myself constantly banging my head against that 140 character limit like a caged bird. I don’t navigate hash-tags well, and typically ignore the “top trending topics” part of my Twitter dashboard. I learned last year why you put a period in front of the @ sign if it starts a tweet. I think I tweet the way my mother uses email — like it’s a necessary tool but goshdarnit if I’m not accidentally hitting “Reply All” when I don’t mean to.

It never really occurred to me that my discomfort with Twitter was a generational thing until I had an opportunity to mentor and interact with some high school-aged students over the summer. The facility with which they interacted with their Twitter and Facebook accounts — the way their digital lives were so closely integrated with their offline lives — was astounding and completely foreign to me. They spent every waking minute attached to their digital selves, even going so far as to Tweet one another while standing right next to each other. 17-year-old Millennials aren’t just addicted to their mobile apps, they are literally living a hybrid life with their digital selves.

I think of Twitter as a transient, ephemeral platform — the current “pulse” of the Internet. A quick glance at one’s own feed, or trending topics, gives you a snapshot of what’s happening right now, but this also results in Twitter having an incredibly short memory. But, for a Millennial, this creates the notion that everyone on Twitter is immersed in, and contributing to, a single massive globe-encompassing macro-conversation, always ongoing and notoriously quixotic. On Twitter, everything is crowd-sourced. Things that are “important” are measured in their ability to focus that giant Twitterverse conversation momentarily on a single topic, be it #DuckDynasty, #2013TaughtMe or #CongratsAlexandSierra (winners of “X Factor”) — all current top trending topics at the time of this writing.

Twitter is not only where Millennials are today, but it is one of the lens through which the world is interpreted. And, I imagine that successfully making #NotYourAsianSidekick the world’s top trending topic for hours is a really big deal. When your world is Twitter, the virality of #NotYourAsianSidekick is akin to picking it up and shaking it. The popularity of #NotYourAsianSidekick is about as big a deal for a Millennial, as me getting something I’ve written to appear on MSNBC’s or Huffington Post’s or Daily Kos’ front page would be for me.

(Yes, Markos Moulitsas, I’m still waiting for you to call me. Fingers crossed.)

So, while Ma wonderfully (and correctly) notes that many of the ideas shared through #NotYourAsianSidekick have been addressed before, they also haven’t been addressed in this medium in a way that engages this audience. And, to have this global conversation ignited in the absence of an inciting incident by a conversation on Asian American feminism (and not just gender-neutral notions of race activism) is, I think, quite astounding. Like Ma, I too was rejuvenated and inspired by the having an identity that has been too-long invisible garner Twitter-wide focus.

But ultimately, the strength of the #NotYourAsianSidekick conversation is not that the subject matter is novel, but that it engages the street-level Asian American Millennial in a way that our previous platforms have not. While Jeff Yang (@originalspin) notes in his piece for the Wall Street Journal that Asian Americans have at our fingertips an “ability to gather a thunderous hammerstrike of digital traffic and drop it from space on an unsuspecting target”, I believe the contemporary Asian American community has always existed predominantly in a digital space. Drawn together by such relics as AsianAvenue.com and buoyed by its successors — online forum boards like YellowWorld.org, Fighting44s.com, and ModelMinority.com (which, by the way, is shockingly still alive) — the modern Asian American movement has always been built upon an online framework.

Today, we are propelled by the writing of top blogs like Angry Asian Man, 8Asians, and others (some might include me in that list). But in contrast to our initial notion that the self-publishing of blogs would — finally — democratize sociopolitical thought (remember when we all thought that?), the reality is that blog readership is still dependent upon traffic. And, only a handful of folks write our community’s top blogs, and are therefore empowered to shape our current ideas of ourselves and our Asian American identity. For the average Asian American, the blogosphere is a passive place, where one reads a blogger’s ideas but does not contribute to changing them.

By contrast, Twitter equalizes every Twerp (Tweep?). It doesn’t matter if you have 8 followers or 8000; if you write something insightful and with the right hash-tag, your voice can have as much reach as Bill frickin’ Clinton’s.

As far as activism is concerned, this kind of democratic energizing and engagement is the quintessential inspiration that can spark a grassroots movement. Millennial Asian Americans are, for perhaps the first time in their lives (if not ours), experiencing true ownership of the Asian American movement. And they are saying in one loud, unified, hash-tagged voice: “let’s do this.”

So, okay, great. But, as I started this post, where do we go from here?

Social movements require sustained commitment, focused energy, and a strong notion of what we’re all working towards. Twitter — as an online tool — is great at reactive passion, but is weak at focusing a conversation. It can’t be good at doing that; it’s not designed to do that. But, social movements need that. Social movements need permanence; they are marathons not sprints.

Suey Park ended her tweeting with the statement that #NotYourAsianSidekick isn’t a trending topic, it is a movement. Park was hoping to inspire activism; in essence, to turn a momentary Twitter interest into a sustained political campaign. I appreciate the sentiment, and (with respect to Suey, since I believe this was her meaning when she tweeted), I want to nuance it:

#NotYourAsianSidekick isn’t a trending topic. It’s part of an existing movement.

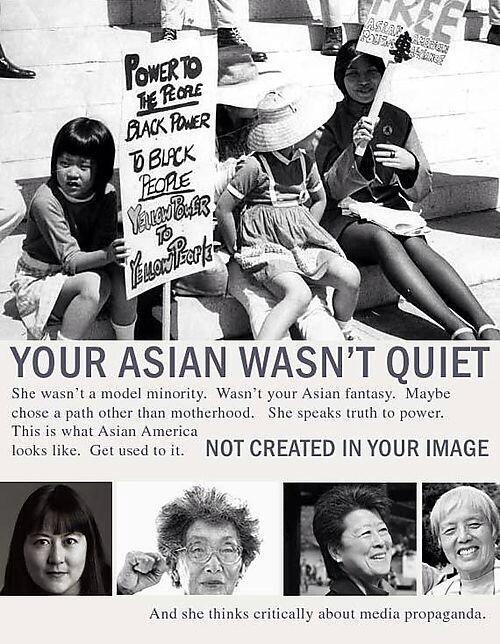

The Asian American (and Asian American feminist) movement has been ongoing since the 60’s and 70’s. We have been fighting for civil rights, and gender equality, for about that long. There is an (understandable) instinct to contrast that long struggle with #NotYourAsianSidekick, with both sides suggesting that each is ignoring the contributions of the other.

With respect to everyone, this is a false dichotomy. Our activisms are not — and do not need to be — mutually exclusive. In fact, we must find a way to integrate our efforts with one another.

#NotYourAsianSidekick is rooted within the ongoing Asian American movement. In fact it found its inspiration as a criticism of contemporary Asian American activism, a criticism that I share. Namely, the overwhelmingly male-dominated nature of our current blogosphere (and academy), and the general inattention that feminism and women’s issues receive. Asian American feminism has in my mind withered under the absence of focused spotlighting of such weighty gender-related topics as the (gendered) wealth gap, body image, and healthcare disparities. Moreover, despite the genesis of Asian American feminism more than 30 years ago, the average Asian American has no better an idea of what Asian American feminism is now than they might have then. #NotYourAsianSidekick hoped to start to scratch the surface of this issue, and its efforts are long overdue.

To proceed from here, #NotYourAsianSidekick could, but does not need to, reinvent the wheel. Instead, #NotYourAsianSidekick can benefit from the experience, and existing audience, of our established blogosphere. #NotYourAsianSidekick can, and should, tap into our existing network of community organizers and successful non-profit endeavours. #NotYourAsianSidekick is a new medium, but it’s part of our movement. We can benefit from #NotYourAsianSidekick’s feminist focus (Lord knows, Asian American race activism desperately needs to); similarly, #NotYourAsianSidekick’s brand of hashtag activism can benefit from our existing organisational framework, the intellectual language offered by our academy, and the greater permanence afforded by the blogging platform.

In truth, every tool through which the Asian American movement has advanced ourselves has its strengths and drawbacks. Twitter can reach in a way that the blogosphere simply cannot. Hashtag activism can inspire in a way that Asian American Studies simply cannot. But, increased reach is tempered with reduced complexity of thought. I’ve long said that ideas fit their spaces, and you can’t jam a big idea into a small space without the idea itself getting smaller.

Furthermore, we must remember that most of our online tools are not reaching every Asian American; we are reaching the Asian Americans with the class privilege to have online access and the leisure time to participate in online endeavours. Neither Twitter nor blogs can reach the economically disadvantaged Asian American without the income or the education or the access to be on the Internet. This large — and thus far invisible — swath of Asian America is still, even with #NotYourAsianSidekick, displaced in our communal conversation because we have dug our roots in online. Arguably, those folks are most in need of the fruits of an Asian American social movement; also, arguably, they will best be reached through boots-on-the-ground “traditional” activism and outreach efforts.

In the end, we — all of us — have the same goals: we are Asian Americans who want race and gender equality for all.

#NotYourAsianSidekick has brought the Millennials into this movement, in a new and exciting way. We’ve got the Millennials onboard (and they’re happy to drive the Twitter bus, while I’m still stuck trying to get my own Twitter account out of Neutral). Rather to get stuck on who thought of what first, let’s figure out how to best incorporate that youthful energy to add fuel to the greater Asian American (and Asian American feminist) social movement. Let’s figure out how to help #NotYourAsianSidekick tap into the population of young Millennials whom the Gen X-ers/Gen Y-ers obviously were not adequately reaching on our own. Let’s figure out how we — all of us — can let this moment evolve our existing social movement.

In the end, no social movement can be built, or sustained, without getting young people involved while still respecting our movement elders. Or, without the movement’s elders learning to let go, step aside, and let the young folks take the reins.

This is our chance to do both.