In a major announcement, the Chinese government committed today to several major changes to national policy.

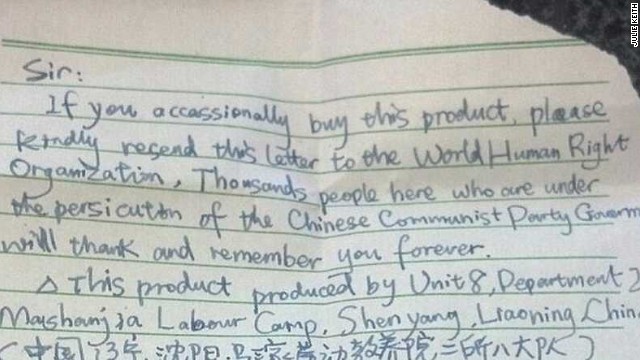

The most profound change comes to China’s controversial (and unambiguously inhumane) “re-education through labour” prison camps, which are part of a forced labour program started in 1957 and which have come under national scrutiny recently for allegations of torture and other human rights violations. The camps were established during the era of Mao Zedong, and were intended to segregate political dissenters away from the general population under the guise of “re-education” or “re-socialization”; hundreds such labour camps are believed to have existed throughout the Chinese countryside at one point. In the last month, major news outlets picked up the story of a man imprisoned at one such camp who surreptitiously sent letters for help to the United States packaged in Halloween decorations sold in K-mart.

In the letters, the man (identified by CNN as “Mr. Zhang” who was sent to a camp for being a member of the Falun Gong spiritual group that China has labelled an anti-government “cult”) describes the daily abuse that he and other prisoners faced during their imprisonment.

Zhang recounted the systematic use of beatings, sleep deprivation and torture, especially targeting those like him who refused to repent. Some gruesome details are too specific to him to be reported.

“Making products turned out to be an escape from the horrible violence,” he said. “We thought we could protect ourselves, and avoid verbal and physical assaults as long as we worked and did the job well.”

Another former inmate as Masanjia (a camp that appears to have been closed recently) whom CNN interviewed offered more details:

As the van carrying her and the CNN crew stopped near the women’s quarters, powerful memories rushed back to this 50-year-old farmer from a nearby village.

“I was confined in that building — Room 209,” she said while standing outside the fence. “We had the 4:15 a.m. wake-up call, worked from 6 a.m. to noon, got a 30-minute lunch and bathroom break, and resumed working until 5:30 p.m. Sometimes we had to stay up until midnight if there was too much work — and if you couldn’t finish your work, you would be punished.”

[…]

“I had to do everything from matching fabrics to sorting materials and cutting loose threads,” she said. “Every day, I had to repeat seven work steps — for about 2,400 steps in total.”

Suffering from high blood pressure and malnutrition, Liu said she once fainted on the job but was denied medical care. For her defiant attitude, she said guards also ordered fellow inmates to beat her twice — their assaults with plastic stools and basins so vicious that she lost consciousness. “But I still had to work after I regained consciousness,” she added. “This place was Hell on Earth.”

However, China’s recent “election” which saw changes to the top positions of the China Community Party and mounting international pressure suggested China was ready to end the labour camp program; a political shift that was cemented with today’s announcement.

China also announced easing of it’s controversial One-Child Policy, a policy that was intended to curtail China’s high population density and booming growth by limiting each family to a single child. International groups estimate that the policy has resulted in the (perhaps unintended although certainly undeniable) abortion, post-natal murder or abandonment of thousands of female children. The male-to-female ratio in China is a striking 118 boys to every 100 girls, and the One-Child Policy along with other “family planning” state policies have encouraged (often dangerous back-alley) abortion and has forced sterilization of women. Furthermore, because the policy can be circumvented by paying a monetary fee, the policy has disproportionately targeted poor and rural families.

However, today, China announced it would be easing (if not eliminating) the One-Child policy by allowing families to have two-children if at least one parent is an only child. While this is likely to improve conditions for women in China, it’s a small step towards a much-needed end to state-dictated “family planning”.

Nonetheless, these changes to state policy are in the right direction, and give me hope that China is willing to eventually step into the twenty-first century when it comes to basic human rights.