httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Il0nz0LHbcM

There’s a video that’s been making the rounds of the feminist blogosphere. It’s a viral ad by Dove, maker of all kinds of skincare, personal hygiene, and, according to Acne Foundation, just recently acne products. This is part of their “Real Beauty” campaign. For a few years now, Dove has been marketing themselves as the enlightened skincare company, charging themselves with exploring and improving women’s self-esteem and beauty image issues (while selling us fresh-smelling soap).

Of course, this is your typical feel-good schlock, right? I mean, a beauty company that cares? We all know that this is largely a marketing ploy designed to target a particular subsect of women, typically older and perhaps more predisposed towards a dialogue on body image and beauty conventions.

Yet, there’s something remarkably heartwarming about the marketing campaign. There’s a part of me that can’t help but think: if Dove is sending a positive message to women about self-esteem and body image, why do I care why they’re doing it?

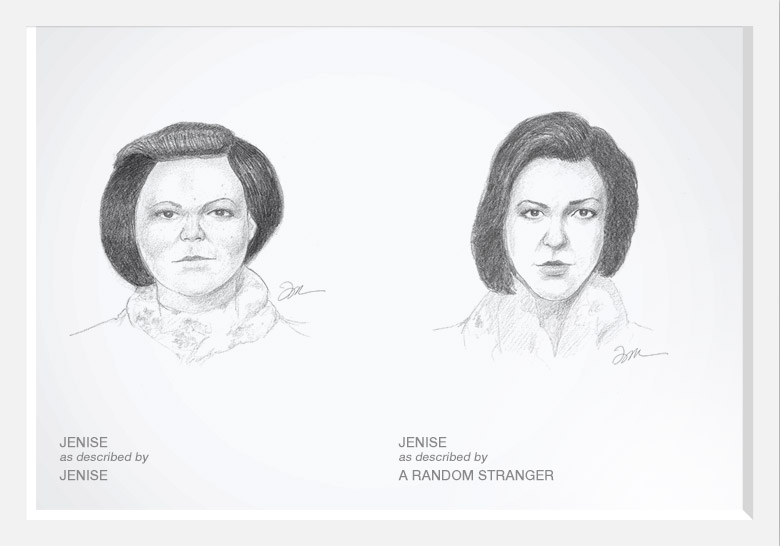

In their most recent efforts, Dove conducted what they’re calling a “social experiment” called “Real Beauty Sketches”. A group of women were ushered into a warehouse where they were interviewed — sans face-to-face contact — by an FBI-trained sketch artist on their appearance. The sketch artist used these details to produce a sketch of the women. A second sketch of the same woman was then produced by the FBI artist based on an interview with a stranger who spent time conversing with her. Both sketches were then compared side-by-side, and the contrasts are immediately evident: there’s an immense gulf between how each subjects sees herself, and how each subject is seen by others.

The power of this campaign is undeniable, and I confess that it resonated with me. They say that a picture is worth a thousand words; in this one simple “experiment”, we are able to see how profoundly a woman’s preoccupation with her physical beauty has distorted her own self-image.

Here’s how: the sketches on the right (based on the descriptions of strangers) can be assumed to be a more-or-less accurate representation of a woman’s physical projection towards the world around her, because strangers carry no specific value biases towards any particular facial feature or another. The sketches are highly symmetrical, and somewhat “normalized” (for lack of a better word), emphasizing how most of us construct and distinguish physical appearance: major features (e.g. shape of eyes, nose and mouth as well as hair and eye colour) are ascribed certain characteristics to produce a unique appearance profile that we then assign to a particular individual; meanwhile, small details are largely glossed over as unimportant or even unseen.

By contrast, the sketches on the left are based on a descriptions wherein particular emphasis is placed on specific facial features and with value judgements assigned to perceived imperfections and flaws, no matter how small. This reflects the relationship that people tend to have with their physical forms: we imagine that everyone is focused on the zit on our foreheads, our protruding guts, or our chicken-thin calf muscles. We forget that the flaws we perceive are not obvious to others, and that they appear monumental because we are focusing on them.

The take-home message in this “experiment” is not that the sketches on the right are innately more “beautiful” (although they are arguably so because they are often more symmetrical due to the lack of distortion through emphasis on perceived flaws; physical symmetry is an innate characteristic of perceived conventional beauty), but that the contrast between both sketches is an undeniable demonstration of the impact of self-perception on overall body image.

Yet, there have been feminists out there who have strongly criticized Dove’s Real Beauty Sketches. One blog post has been making the rounds, written by Jazz of little drops. In it, Jazz makes a few arguments against the campaign.

First, Jazz argues that the campaign is not racially diverse:

When it comes to the diversity of the main participants: all four are Caucasian, three are blonde with blue eyes, all are thin, and all are young (the oldest appears to be 40). The majority of the non-featured participants are thin, young white women as well. Hmm… probably a little limiting, wouldn’t you say? We see in the video that at least three black women were in fact drawn for the project. Two are briefly shown describing themselves in a negative light (one says she has a fat, round face, and one says she’s getting freckles as she ages). Both women are lighter skinned. A black man is shown as one of the people describing someone else, and he comments that she has “pretty blue eyes”. One Asian woman is briefly shown looking at the completed drawings of herself and you see the back of a black woman’s head; neither are shown speaking. Out of 6:36 minutes of footage, people of color are onscreen for less than 10 seconds.

I’m honestly fairly confused by this comment. Out of the seven featured portraits on the Dove site, two are of African-American women and one is of an Asian-American woman. True, this does mean that a full 57% of portraits are of Caucasian women, but I would hardly say this renders the campaign monolithically White. Additionally, it’s clear that other women, whose portraits are not on the website, are also of non-Caucasian descent: at least one other African-American woman, and a darker-skinned (possibly Middle Eastern?) woman at 2:31 of the video above — both participated. None of these women of colour strike me as noticeably “lighter skinned”, or that they are somehow less representative of their race due to the particular shade of brown of their skin. Regardless, the comment troubles me: if the purpose of the “experiment” is to explore self-perception and identity, I don’t see how the experiment is made more or less valid by insufficient racial tokenism.

Jazz goes on to say that her primary problem with the ad campaign is that it emphasizes what some have termed “looks-ism” in our society — that people (male and female) are judged at least in part based on how we look.

….[M]y primary problem with this Dove ad is that it’s not really challenging the message like it makes us feel like it is. It doesn’t really tell us that the definition of beauty is broader than we have been trained to think it is, and it doesn’t really tell us that fitting inside that definition isn’t the most important thing. It doesn’t really push back against the constant objectification of women. All it’s really saying is that you’re actually not quite as far off from the narrow definition as you might think that you are (if you look like the featured women, I guess).

I get where Jazz is coming from, but I ultimately disagree with this take on the Dove campaign. I think this reflects a general misunderstanding of what the Dove campaign is trying to get at, one that — to be fair — Dove perpetuates in its editing of the video. As I write above, the point of the campaign (in my opinion) isn’t that the stranger-generated sketches are more generically beautiful, but that they are widely different from the sketches based on a person’s self-description.

Or, from the tagline of the campaign: it’s not “you are more beautiful than you think”; it’s “you are more beautiful than you think“.

The message isn’t that women should place greater value on our physical beauty (despite voice-over interview snippets to the contrary), but that we should stop internalizing our own distortions of our self-identity.

Ultimately, what I think troubles feminists like Jazz is that physical appearance matters — for men, for women, for just about everyone. Jazz is frustrated by a subject’s comment at the end of the video:

And actually, it almost seems to remind us how vital it is to know that we fit society’s standard of attractiveness . At the end of the experiment, one of the featured participants shares what I find to be the most disturbing quote in the video and what Dove seems to think is the moral of the story as she reflects upon what she’s learned, and how problematic it is that she hasn’t been acknowledging her physical beauty: It’s troubling,” she says as uplifting music swells in the background. “I should be more grateful of my natural beauty. It impacts the choices and the friends we make, the jobs we go out for, they way we treat our children, it impacts everything. It couldn’t be more critical to your happiness.”

[…]

What you look like should not affect the choices that you make. It should certainly not affect the friends you make—the friends that wouldn’t want to be in relationship with you if you did not meet a certain physical standard are not the friends that you want to have. Go out for jobs that you want, that you’re passionate about. Don’t let how good looking you feel like you are affect the way way that you treat your children. And certainly do not make how well you feel you align with the strict and narrow “standard” that the beauty industry and media push be critical to your happiness, because you will always be miserable. You will always feel like you fall short, because those standards are designed to keep you constantly pressured into buying things like make up and diet food and moisturizer to reach an unattainable goal. Don’t let your happiness be dependent on something so fickle and cruel and trivial. You should feel beautiful, and Dove was right about one thing: you are more beautiful than you know. But please, please hear me: you are so, so much more than beautiful.

Look: I get it. Society has historically placed the value of women squarely on our appearance. We are still judged, at least in part, by our attractiveness, and studies have shown that this has strongly impacted a woman’s professional and personal success. The struggle women face in the workplace as offering value beyond our beauty recently made headlines when Obama quipped about Kamala Harris as California’s “best-looking” district attorney; he subsequently apologized calling the incident a “teaching moment”. In my own male-dominated industry, the appearance of female scientists is often remarked upon in the same breath as her intellectual contributions to her science.

Women clearly need to fight against this undue emphasis placed upon our physical appearance over our intellectual and professional skillset. We aren’t just pretty people and shouldn’t be treated (or treat ourselves) as such.

But, I would also assert that the quest by some feminists to completely eliminate the impact of physical appearance on self-perception, self-identity, and societal treatment is, in essence, a quest for pure truth. Women, like all humans, are physical beings, and the simple fact that each of us bear a unique physical appearance will impact our participation in the world around us. Male or female, how we look shapes who we are and how we think of ourselves, and will certainly impact how people treat us.

I can’t help but draw an analogy to race. To me, the argument that we can move towards a “post-looks” or “post-attractiveness” society sounds a lot like the flawed concept of a “post-racial” society wherein people purportedly don’t see racial difference. I have always had a problem with this notion on two counts: 1) being — and appearing — a (specifically phenotypically East Asian) Asian-American woman is a fundamental part of my self-identity and how I perceive myself; and 2) I wear my racial/ethnic identity on my skin, and am treated by others in a unique way because of it. My appearance — racially — is immediately obvious and impacts every social interaction I have with others (no matter how subtly). It influences my very presence in the world.

When people meet me, they don’t see a person with vague, non-descript, racial appearance. If they say they do, they are lying. I’m going to go out on a limb and say there are no colour-blind people. Every time a person notices I’m not White; every time they wonder what “brand” of Asian I am; every time they ask me what language(s) I speak or where I grew up; they are racializing me. I don’t necessarily say this as an indictment (although it can sometimes be). I say this as a simple statement of fact about my life.

How I look totally influences my life.

The simple truth that physical appearance matters when it comes to race is even evident in Jazz’s post (as it is in mine). As I noted above, Jazz makes a quick assertion about the races of the various study participants, based on their physical appearances. Shelly, Lani and Maria — the three women of colour whose portraits are featured on the Dove site — are singled out for their racial tokenism; thus, in race, the physical appearances of these women clearly matter. They have clearly influenced how these women are treated by the world around them. They have certainly influenced how feminists are judging the racial comprehensiveness of the Dove campaign.

Perhaps this is why I’m not all that troubled by the notion that my physical appearance, in general, will also shape how others see me. To me, the suggestion that more fundamental aspects of physical appearance such as hair colour or jaw shape or basic facial symmetry should have no impact on one’s social interactions when racial phenotypes clearly do strikes me as fallacious, and simply inconsistent with my own experiences as a person. I can’t help but feel that folks who advocate an end to looks-based treatment are speaking from a place of racial privilege, wherein the privilege allows for an absence of noticeably altered treatment in the world based on racial physical appearance, and so there’s an assumption that non-racial physical appearance can be similarly unimpactful.

Now, like I said above, I clearly do not support boiling a woman down to only her appearance. And, of course, Westernized conventions of beauty are clearly too Euro-centrically narrow. I agree with Jazz’s basic take-home message: we women are so much more than beautiful.

But, I would also hazard to say this: we are also beautiful. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with that. There’s nothing shameful in that.

I suggest that rather than to argue against the very concept of physical beauty existing in this world, that we instead work towards expanding our strict and narrow parameters of what we define as physical beauty, and in so doing, de-emphasize its impact on our perceived self-worth (as men and women).

Because, in the end, this shouldn’t be about shifting our focus from one isolated characteristic of ourselves to another. This can only lead to a different form of distortion. Instead, we should promote holistic self-image, and this must necessarily include the fact that we all have physical bodies with unique — and yes, often beautiful — appearances.