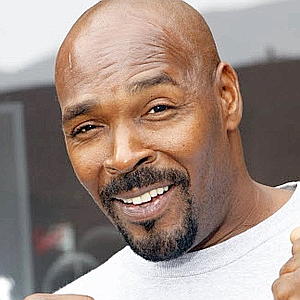

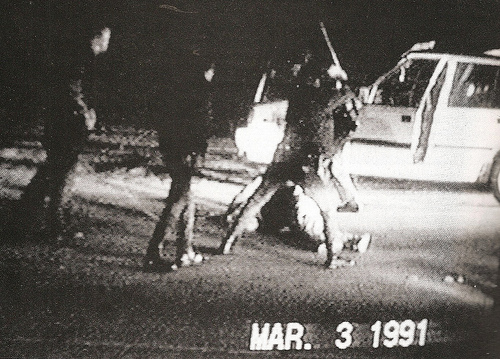

The news just broke that Rodney King, whose videotaped beating at the hands of LAPD in 1991 and the subsequent acquittal of the participating officers, triggered widespread rioting including the infamous LA Riots, has died. He was 47.

CNN reports that King was found dead this morning at his home by his fiancee. He is believed to have drowned in his backyard pool, and police don’t believe that foul play was involved.

With only a few moments to process the importance of King’s death, I can’t help but react with sadness: Rodney King’s was a life over-shadowed by race. The police who attacked him took from King the chance to live a life outside of the spotlight. For our part, we were accomplices: we made King — and his beating — into a powerful symbol of racial injustice, forgetting that he was also just a man.

In the coming week, it’s likely that King’s death will rejuvenate discussion over his 1991 beating, the subsequent trials, and the corresponding riots. We will talk about race, police brutality and the justice system. We will talk about the landmark importance of the riots in energizing the African-American community, and how it helped raise awareness about racial bias against that community at the hands of local officers and the justice system.

In all this discussion, let us not forget the victims of the L.A. Riots. The 1992 L.A. Riots resulted in widespread targeting predominantly of Korean-American immigrants, particularly small business owners who served predominantly African American communities. There was also widespread looting of those businesses resulting in millions of dollars in property damage. Countless armed showdowns occurred between looters and members of the Korean-American, which gave the appearance of an all-out race war. The L.A. Riots would later be known as Sa-I-Gu within the Korean-American community, and has become a prime example of the ongoing interracial tension between the Black and Asian communities that continues into today.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r6BF6uO_b38

In the aftermath of Sa-I-Gu, Asian Americans wondered why our community bore the brunt of racial anger expressed by the African-American community against White cops. We wondered why Koreans were abandoned by L.A. police, and forced to arm and defend themselves. We were also forced to face the racial implications brought on when Korean-American immigrants enter into all-Black, economically-stressed enclaves to open businesses, siphoning money out of those communities. We had to contemplate whether we had contributed to inter-ethnic tension by permitting Korean-American business owners to treat their own clientele with suspicion and sometimes even open racial hostility.

Looking back at the riots today, I am struck by how little relations have improved between the Black and Asian communities. Racism remains between Blacks and Asians with few examples of shared political interests and efforts. Few inroads have been made between our communities, and there is little consideration (by either side) about coalition-building over common issues like race, education, healthcare, and police brutality. At the risk of appropriating King’s death as we have appropriated his life, I hope we can take this opportunity in the coming weeks to re-examine how the African-American and Asian-American communities interact with one another, and find ways to improve it.

On a semi-unrelated note, it’s also ironic to me that next week marks 30 years since the racially-motivated murder of Vincent Chin at the hands of Ronald Ebens and Michael Nintz. Like Chin, King was a symbolic figure who helped galvanize his community towards political action and activism. But, like Chin, King’s infamy was less about him as a person, and more about the circumstances of his beating (and in Chin’s case, his death). In some ways, King’s life reminds us of the pressure of that kind of fame and notoriety, and the stress of trying to live one’s life to the standards of being cast into the role of a sociopolitical icon. I can’t help but wonder — had Chin lived — what his life would have been like. Would he have been a proud symbol of racial activism? Would he have suffered under the pressure of an entire community looking to his beating — but not him — for inspiration? It saddens me that we may never know.

The bottom line is that both Ronald King and Vincent Chin (and others, like Trayvon Martin) were victims: victims of institutionalized racial hate that indelibly marked — perhaps for better and perhaps for worse — their lives and their legacies. We may never know what life King might have lived had he not been stopped or beaten that night in 1991, but we do know that he will go down in history as yet another life that was forever changed by the ugliness of race in this country.