By: Victoria M. Huỳnh

Nearly eight months into 2020, and there is so much to grieve. We are amidst a global pandemic leaving Black, Indigenous, incarcerated, and immigrant communities most vulnerable. Black-led uprisings in the imperial core enraged by the white supremacist murder of George Floyd should have shaken the world awake again: the US internally robs and exploits Black life in duty of its imperialist project that is the US empire. Worldwide, the US empire continues to manifest its devastation in crippling US economic sanctions amidst the bombing of Lebanon, ongoing US-backed Israeli occupation of Palestine, impending US imperialist aggression to China towards a Cold War 2.0, and more.

To locate this moment, as non-Black Asian diasporas in the imperial core seeking solidarity with Black and other Third Worlded peoples, is to know this moment is fraught with deep struggle since times before ours. It is also yet a testimony to the urgency of committing to Black revolutionary praxis in their fight for a new world— knowing no Black life should have been lost to US empire in the first place. If we fall back on bell hooks’ reminder that, “love is profoundly political. Our deepest revolution will come when we understand this truth,” we are forced to rethink what is so necessarily meant by “love” in and beyond these times. And if solidarity is love, we should be pushed to pursue a solidarity that is not just conscious of being against white supremacy, US imperialism, patriarchy, or global capitalism [wrongfully marketed] as separate systems– but a solidarity for an anti-imperialist, socialist, decolonized world that necessitates Black liberation– and which knows we must take down the US empire in its entirety to achieve so.

If solidarity is love, we should be pushed to pursue a solidarity that is not just conscious of being against white supremacy, US imperialism, patriarchy, or global capitalism [wrongfully marketed] as separate systems– but a solidarity for an anti-imperialist, socialist, decolonized world that necessitates Black liberation– and which knows we must take down the US empire in its entirety to achieve so.

It is in this context that we must reground ourselves in beginnings planted deep in and made possible by anti-imperialist feminist love founded in the 1960s feminist Black-led, Third World left. In their interrogation of US imperialism’s devastation born by Black and Third Worlded women for their peoples, they knew: under global capitalism, liberalism and its siblings, democratic-socialism and fascist US “progressivism”, keep us reaching for solidarity and liberation as fabricated ideals; scientific socialism under the anti-imperialist banner of the 1960s feminist Third World left, principled in anti-imperialist feminist love, give us the tools to fight for them.

Solidarity as Black & Asian feminist love forces us to rethink what is meant by “love”.

When Audre Lorde calls on the power of the erotic — or love– she delivers a warning:

“The erotic [love] has often been misnamed by men and used against women… For this reason, we have often turned away from the exploration and consideration of the erotic as a source of power and information, confusing it with its opposite, the pornographic. But pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling. Pornography emphasizes sensation without feeling.”

This is why we relate her words to the sensationalization and fetishization of not only Black death, but also Black resistance by the white supremacist state today. In other words, the radicality of Black revolutionary movement-building founded in the love and commitment to a world in which Black and brown people are free of all of the US empire, is reduced by bystanders into infographics, watered-down slogans you can wear, and a commodified aesthetic you can perform for capital. The Amerikan public consumes Black trauma and the quick-fixes liberalism offers, fixated on the idea that change can be guaranteed simply by the “representation” of “revolution”. Bourgeois Amerika now knows the language, performs it, but in turn has removed “revolution” from the depth of its materialist principles. It is no accident we’ve seen multinational corporations — the biggest benefactors of anti-Black exploitation globally — co-opt revolutionary language and transform it into scripted solidarity statements for “#Blacklivesmatter” and transactionary donations to satisfy the guilty Amerikan conscience. Large organizations, non-profits, politicians, social media influencers and general social media boosts have made momentary and reformist solidarity statements, all whilst they side-step the demands of radical organizing from materialist abolitionist socialist groups. Global capitalism will have us believe that so-called “liberation and solidarity” look and feel like something we can quickly digest, consume, sell, vote and tack on.

But the irony of such tactics under liberalism is its promise to enable “racial justice”, when the murder of Black, Indigenous, and Third Worlded people is inherent to Amerikan capitalism and empire-building. That is why: feminist love requires we reconnect our minds and hearts with a deeper, anti-imperialist and socialist feminist struggle, which sees love as a practice rooted in militancy. Love grounds us in the material realities of Black and brown colonized peoples— as not just distant abstractions, but peoples whose lives should not have to be ravaged by imperialism in the first place– nor any more. Solidarity as love then recognizes that we not only need to reduce the harm caused by the “survival” of imperialism, capitalism, and patriarchy — it necessitates we dismantle these forces altogether.

1960s Black and Asian Feminist solidarity was founded on a radical global sisterhood under an anti-imperialist socialist banner.

While many displaced Asian diasporas may hesitate to engage with writings that read socialist slogans in our mother tongues, the simple fact is this: anti-imperialist feminism is rooted in socialist and communist resistance. Anti-imperialist feminist love was never isolated to theory; it has always been reflected by and shaped in terms of the material conditions of the people, birthed in Marxist-Leninist socialist uprisings.

A critical analysis of racial capitalism helps us understand that racism and misogyny are tools that perpetuate classism in the lived realities of racialized, gendered people throughout the US empire. Accordingly, bourgeois white/liberal feminism continues to advance an insufficient facade of multiculturalism and “inclusion”, one that violently reproduces the flawed illusion that racialized, gendered, and colonized peoples can find liberation within and from the US settler-colonial state that was premeditatively built to exploit them.

The significance of the feminist Third World left, then, is not solely in that they have come together as a multiracial group of women, but also that they have organized and rooted themselves in socialist and communist practices to resist modalities of racism and patriarchy that act as byproducts of imperialism and capitalism.

The significance of the feminist Third World left, then, is not solely in that they have come together as a multiracial group of women, but also that they have organized and rooted themselves in socialist and communist practices to resist modalities of racism and patriarchy that act as byproducts of imperialism and capitalism. The Combahee River Collective wrote:

[W]e realize that the liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy. We are socialists because we believe that work must be organized for the collective benefit of those who do the work and create the products, and not for the profit of the bosses… We need to articulate the real class situation of persons who are not merely raceless, sexless workers, but for whom racial and sexual oppression are significant determinants in their working/economic lives. Although we are in essential agreement with Marx’s theory as it applied to the very specific economic relationships he analyzed, we know that his analysis must be extended further in order for us to understand our specific economic situation as Black women.

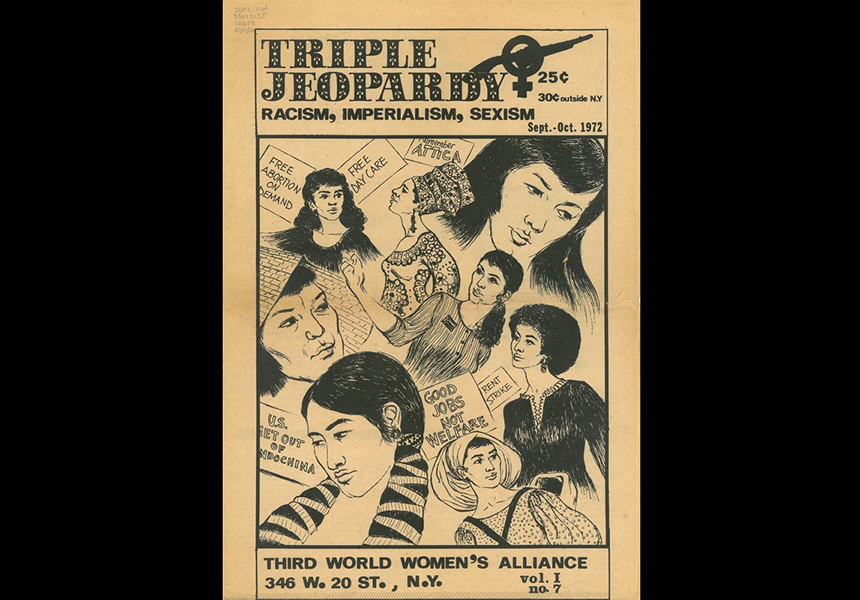

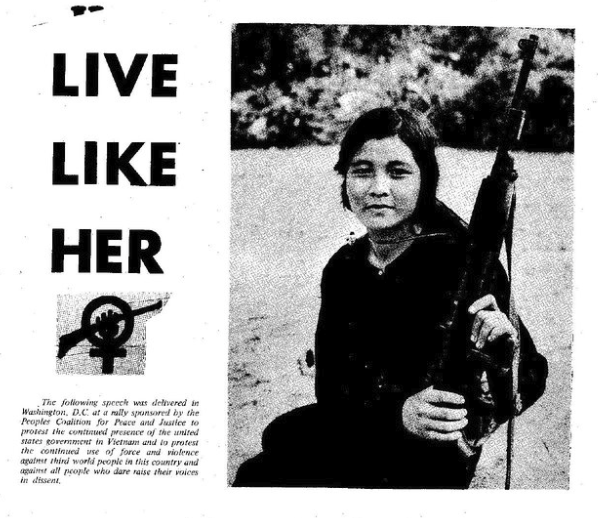

Thus, the birth of the feminist 1960’s era, Black-led, Third World left saw to reclaim their specific working-class realities by looking to the development of the feminist international proletariat. Under the title “Live Like Her” — in reference to a militant Vietnamese woman — authors of Triple Jeopardy (the Third World Women’s Alliance) wrote:

We women have learned that the struggle against imperialism and its side effects; racism, sexism, and exploitation, are not restricted to the United States but are world-wide, transported through the henchmen and lackeys of the monied classes who control nearly three-fourths of the world — including most third world countries.

Extensive reading of early Third World feminist writing reveals further anti-imperialist socialist solidarity ingrained in the praxes of Black diasporic and Asian diasporic women who cited socialist Chinese, Viet, Filipina and Korean women as feminist iconographies and who wrote various articles in Triple Jeopardy, a journal that called for the elimination of U.S. militarism in various limited wars in the Third World. It is by no accident that their pamphlets condemn Israeli occupation of Palestine, sanctions against Cuba, and sites of imperialist aggression that live out today.

The 1955 Bandung Conference, the 1971 Indochinese Women’s Conference, and the formation of other International Women’s Conventions also reveal transnational exchanges that furthered anti-imperialist feminisms. The transnational work of revolutionaries, such as Vicki Garvin, Elaine Brown, and Claudia Jones — who were exiled to socialist China, Cuba, and Ghana — pushed against the essentialization of Black diasporic feminism and Asian diasporic feminism as a solely “Western”-sourced methodology. Cross-connections between North Vietnamese revolutionary leaders like Nguyen Thi Binh and diasporic women like Pat Sumi demonstrate anti-imperialist feminisms sourced and originated in the west but something that actually collectivized and was dialectically influenced by Third Worlded women. At its crux, anti-imperialist feminism was born from the rise of the international proletariat across-borders.

While BIWOC & feminized labor under capitalism is invisibilized and devalued, it is our duty to see (and visiblize) each other.

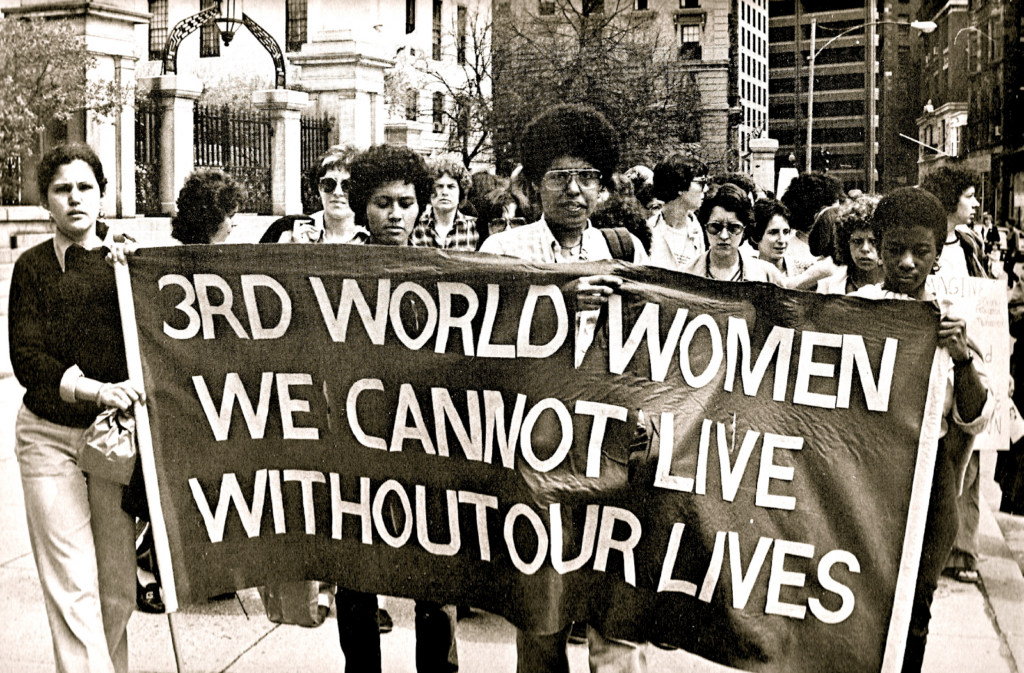

The breaking off of originally Black Women’s Liberation Committee, later the Third World Women’s Alliance (TWWA), from the Student Nonviolent Committee and other “brotherhoods” in the 1960’s signified their simultaneous and active rejection of patriarchal chauvinism and proclamation for feminist communalization. The Combahee River Collective statement read:

[W]e realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us. Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work.

Our duty, as non-Black Asian diasporas seeking solidarity with Black and other Third Worlded peoples, is not to any bourgeois institution; our duty is to each other. Their community-building efforts, such as through political education programs, publishing and archival work, survivor centers, r*pe crisis centers, health care support programs, and healing practices, sustained Black and brown communities both inside and outside of the imperial core (the United States) — emotionally, spiritually, and physically. Instead of idolizing individual masculine martyrs — as if these “exceptional men” are needed to sustain a movement — Black feminism has shown us how collectives of Black femmes and their investment in community care unfreezes revolutionary subjects from being objectified by any one moment in history.

TWWA wrote in their political educational editorial Triple Jeopardy:

[A]s Third World women, we realize that we don’t have to bear children for the revolution, we don’t have to walk behind men, and we don’t have to stay at home when the action is happening in the streets.

In contrast to the rendering of socialist Third Worlded women as passive victims necessitating white imperialist saviorism, the Black, Puerto Rican, Latines, and Asian authors of Triple Jeopardy declared heroes the socialist femme fighters, and painted an active retaliation of liberation front heroines. They furthered a framework for feminist militancy that broke free from the constraints of biologically determinist reproductive labor and held true their embattlement with the imperialist conditions that US imperialism and global capitalism enable. Global sisterhood and femme homosociality showed us how to imagine and learn from multiplicities of resistance that have and continue to take place around the world vis a vis an anti-imperialist feminist calling.

They made evident: you cannot be in solidarity with peoples whom you objectify, fetishize or tokenize for your idealizations of them as objects of revolutionary history; solidarity as feminist love requires we think of Black feminists and Asian feminists as complex and whole human agents in an active, moving revolution. In what bell hooks would call “moving from object to subject”, love as an ethic means we first and foremost see ourselves and each other as living members of our own communities.

Solidarity as feminist love requires we think of Black feminists and Asian feminists as complex and whole human agents in an active, moving revolution.

Solidarity is love is camaraderie is committing to fighting for the reality Black liberation requires.

Feminists of the Black-led, Third World left in the 1960s have taught us love looks like queer love that teaches us multiplicity, community love that sustains a movement, enraged love that is taking apart patriarchal domination, grieving love that comes from holding so many on our backs, and, most importantly, intentional love that brings us back to the commitment to Black liberation and the abolition of the anti-Black and anti-Indigenous U.S. carceral state, capitalism, its imperialist grasp on the Third World, and any and all of its militarist branches.

That is why anti-imperialist feminist solidarity sees that the significance of calling out U.S.-backed Israeli occupation and military violence in Palestine, condemning U.S. aggression towards China on the brink of a Cold War and all US aggression towards Third Worlded countries, must be in tandem with commitment to Black women, femme, and trans led abolitionist organizing. This already manifests in mutual aid cross-borders and within vulnerablized communities, defunding police and US military spending and occupation across the world, survivor-centered care centers and programs, the militant transnational organizing and radicalization of colonized working-class peoples towards a socialist reality, and so much more.

In other words, this feminist love underlies wanting to be, see, and live in a free world together, and fighting for Black liberation via the means of anti-imperialist socialism to get there. Solidarity is love… is camaraderie… is committing to fighting for the reality Black liberation requires.

Succinctly: a revolutionary love is one that gets the people free.

Victoria M. Huỳnh (she/they) is a Cambodian-Viet-Teochew student of anti-imperialist Asian feminism. She is an undergraduate student organizer learning how to write, teach, and speak resistance.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest writing program and submit your work here.