By Guest Contributor: Alison Roh Park

This essay originally appeared on Medium.

Within six months of Crazy Rich Asians’ much anticipated release, I was physically assaulted by a White woman in furs on the 6-train in New York City. She shouted at me to go back to China, and shortly thereafter I was verbally assaulted on the 1-train by a musician/busker (and a middle-aged Black gentleman) whom I didn’t have a donation for. Ironically, this was all while I was seated across from two White women also wearing fur.

Asian American New Yorkers have the greatest internal wealth disparity than any other group. Chinese Americans are disproportionately represented under the poverty line, while headlines about massive Chinese real estate buys and a so-called U.S.-China trade war loom on every outlet. This plays out for urban Asian Americans on the hyperlocal level in New York City — for instance, in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, overseas Chinese real estate buyers and developers are gentrifying and displacing longtime Chinese residents of this historic neighborhood.

Meanwhile, Asian American women remain pointedly invisible. Shows like The Expanse and Top of the Lake: China Girl (literally — with the White feminist superstar Elizabeth Moss investigating the rape and disappearance of a virtually mute 12 year old Vietnamese girl) hinge on the idea and trope of “Asian Women” and as victims of sexual violence whose end is inevitable, while simultaneously obliterating them from the actual substance of the show.

Today, the stories of two two Asian American women epitomize these erasures and the outcomes of media racism against Asian women: 1) Chanel Miller, an Asian American woman, came out as the survivor of Brock Turner’s heinous rape and his all-powerful intergenerational White privilege; and 2) Adele Lim, the lead Asian American writer on a pretty much all-white team, exited the sequel deals (you go girl!) because, um, $110K for an Asian person vs $1M for a white person — both veterans in their respective crafts — is pretty baldfaced.

This is the local-to-global context in which Asian American love lives for Hollywood. In Crazy Rich Asians, for example, a bootstrapping model minority Asian American from Flushing meets a hot, more western-featured Singaporean Prince Charming, whose family has amassed primitive wealth through land grabs all the way down through Southeast Asia.

In a US where Americans, including Asian Americans, see themselves as being a monolith, this movie seamlessly blends racist tropes into a Cinderella narrative of class mobility via heteronormative love. The danger? That it also naturalizes and cements the existing social order around race, gender and class.

In a US where Americans, including Asian Americans, see themselves as being a monolith, this movie seamlessly blends racist tropes into a Cinderella narrative of class mobility via heteronormative love. The danger? That it also naturalizes and cements the existing social order around race, gender and class.

The colonial logics of Crazy Rich Asians

As an American-Born Chinese (ABC), Rachel Chu is a proxy for the scrappy White feminist who both saves and triumphs over the Orientalized (not creolized) old world “auto-matron” Ms. Young (with a British name no less!)— a la Virginia Slims meets Blade Runner Dragon Lady. As an American, Rachel introduces her would-be mother-in-law to things like passion, love, individuality and even good parenting. Crazy Rich Asians is Joy Luck Club 2.0 — itself The Teahouse of the August Moon 2.0 — albeit each with variations and expansions.

In the backdrop of Crazy Rich Asians, other “types” of Asians are layered in, revealing while otherwise collapsing the impossibility of race. Scowling, silent South Asian paramilitary (a direct output of British colonialism throughout Asia from Punjab to Pulau) emerge from the shadows to scare the silly Peik Lin and Rachel. Dark, demure women in non-western dress murmur and retreat into the background to serve the Youngs and their posh cosmopolitan crew, completely useful and almost neither seen nor heard.

Faceless mahjong dealers “only speak Hokkien,” in stark contrast to Rachel Chu and Mrs. Young — power brokers negotiating in the inflected English of two world powers across two generations of Asian womanhood (one west, one east, one old, one young) — for the main bargaining chip of the movie, a handsome rich straight guy with big dreamy eyes and a British English accent.

Nick’s male cousins, more phenotypically East Asian, are the epitome of Asian masculinity within colonialism — unable to keep the girl, keep it up, or keep it in their noveau riche suit pants — again, whatever the storyline demands. The most salt-of-the-earth male character, Astrid’s “commoner” husband Michael, fumbles into inevitability, too consumed by his shortcomings, male insecurities, and sexual lust to sustain his nuclear family. In order to maintain the same, his brother-in-law Edison on the other hand must be robotically obsessed with the appearance of success and normality, while Peik Lin’s dad’s tight knit family is still bound by decadence and their own dysfunction that runs dangerously parallel to Hollywood’s portrayals of blackness.

The writers even manage a hat tip to the angry patriarchal Asian father figure with a dropped-in story line about Rachel’s mom’s abusive husband, again positioning the West as a safe haven for Asian women fleeing violent old world homelands. This plot detail is presented without any constructive framing around the very real collective experience of domestic and sexual violence against Asian American women and girls.

Anti-Black and anti-Asian racism do the same thing — cloak White supremacy

Further irony ensues when one notices the subtle American-style Black appropriation in the backdrop. Jazz is the “western” music we hear — performed by Asians in Asia, this time — letting the viewer know that these are people who are so like-Whites they also can borrow cache from African American-derived art forms in the utter absence of Black people in a context where their own Orientalized identities and cultures fall short of human.

This is how people of color globally — 80 percent of the world’s population and the source of most of our goods, labor and materials — demonstrate class status and “arrival” within imperialism — to master, perform and appropriate — similar to R.Kelly or Ludacris’ or any number of other music videos that rely on anti-Asian colonial tropes (geishas, massage, samurai sword fights, mastery of Kung Fu) to elevate one’s respective status.

The Young family estate is impressive not just for the sheer grandeur of it — it’s the command of both East and West, a kind of “occidentalism.” The main house is white and pillared. As you go deeper into the darkened grounds, Chinese architecture stoically protects exotic flowers that only bloom in the night.

Whether or not one looks for the Other (or at least symbols of the Other) out of disenchantment or aspiration, the colonial logics of both Crazy Rich Asians and certain Black American media drives a search for power — as well as personal fulfillment and a sense of identity — not only on the backs of other (non-wealthy) people of color but in opposition to them — in wildly subconscious ways and with real material outcomes.

Erasing poverty, erasing Asian women’s stories

Constance Wu plays a New York University economics professor, and a daughter of a single woman in Flushing, Queens — a neighborhood not far from mine where I went to high school and continue spent much of my time. While Awkwafina is from a nearby residential neighborhood near Flushing, Constance Wu herself is from Virginia, a place probably more akin to the setting of her sitcom Fresh Off the Boat.

The suburban-urban divide is a good place so start to authentically understand what it means to be Asian American, and the experiences of Asian women particularly is a good place to start mapping that out.

Up until a decade ago (and maybe still), over 50% of the Korean American population could trace their US nationality back to post-WWII “war brides” (Yuh). Moreover, the War Brides Act was passed and amended alongside the evolution of the suburbs. Through marriage to the agents of Korea’s new colonial government (the US), Korean and other Asian and Pacific Islander women immigrated to suburbs across America.

Since the 1940’s, it was these women who exposed people in suburbs to real-life Asian women (as opposed to those seen by Whites in movies, museums, and circus exhibits) before later legislation ended a century of race-based exclusion. Immigration entry points and over a century of war and Orientalized and hypersexualized representations of Asian femininity combine together into the simultaneous erasure and hypervisibility of the Asian American female.

Constance Wu plays a familiar suburban girl-next-door character (except she’s Asian and from Queens) whose successful assimilation means she apparently doesn’t have to deal with what other Chinese women in Queens have to deal with — massive displacement, wage and hour exploitation, poor work and housing conditions, endemic sexual harassment and violence. I don’t know how many more ways to say this so that it lands, but regardless of White liberal and reactionary POC media coverage of affirmative action and the SHSATs, Asian Americans are the poorest New Yorkers and personally, anecdotally and statistically, hate crimes targeting us are definitively on the rise.

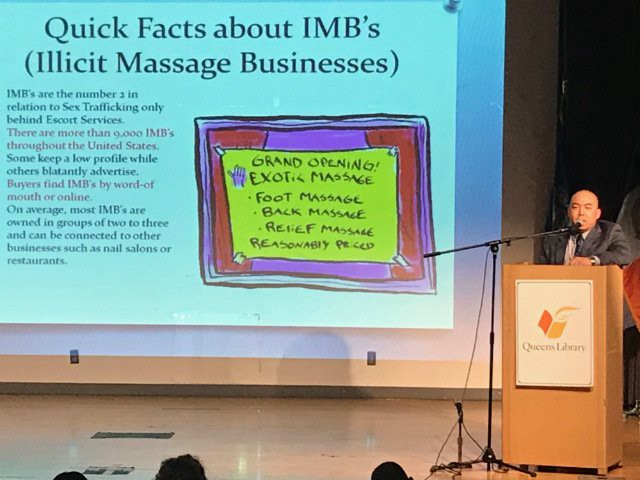

Just recently, the NYPD (led by an Asian American male lieutenant no less) launched a new campaign targeting massage businesses in Queens in the face of protest. From Gothamist: “Protesters repeatedly invoked Yang Song, the Flushing massage parlor worker who, after cycling through the criminal justice system, died falling from a balcony during a police sting in November 2017. Before the fatal encounter, Song reportedly said she was being pressured by police officers to become an informant and reported being assaulted by a man who said he was a law enforcement officer.”

Since Crazy Rich Asians, Constance Wu continues her career based on implicit yellowface and plays a Southeast Asian American sex worker — the first story of a Cambodian woman the US will see on the silver screen — in a blockbuster movie. While Wu goes on as “that” Asian American actress (because, you know, we only get one) of her generation, millions of other Asian American women actors continue to play hookers, whores and mistresses, rape and murder victims, or are simply just written into the storyline, sometimes as the crux, without any actual scenes or dialogue. Even as this happens, we grapple with the revelation that Brock Turner’s silenced and forcibly unknown victim has revealed herself to be a powerful Asian American woman. These representations matter, and no matter how glittery or ingratiating they are — they continue to erase us and make us targets of racist and sexist violence.

Why we still love Crazy Rich Asians

Asian Americans loved Crazy Rich Asians. I watched it like a terrible accident unfolding in slow motion, with amazing wardrobe and styling and the grotesque wealth of a Disney fairytale and understood 100% why people love the movie. For a second, we can imagine we are fully human. That a rich man with big double-lidded eyes could love a working class girl from sullied roots. That is, if we are rich — and hetero — and in Asia.

We imagine we are Asian, and that being Asian American means something. And yet, you will not be able to find a singular definition of what those identities mean. Instead, we cling to invented Subtle Asian Traits that make self-hate a viral phenomenon.

The Asian American designation was never supposed to be cultural, commercial, and self-essentializing.

The designation Asian American was never meant to be something that keeps us as foreign cultural ambassadors in a white or black world. It came out of the solidarity between Asian Americans and Black Americans in the people’s movements of the 60s, 70s and 80s and an insistence on a politically unifying racial identity. The Asian American designation was never supposed to be cultural, commercial, and self-essentializing.

Alison Roh Park is a writer, poet, and editor of Urbanity Mag.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest writing program and submit your work here.