By: Karin Wang (@naragirl), Asian Americans Advancing Justice

Since we launched “Write Back, Fight Back” two months ago, we have witnessed the power of words to name our struggles, reclaim our identities, and voice our power. We close out our series by centering the story of Asian immigrants challenging racism through the courts and in many cases, winning and changing the course of American history.

No current narrative of Asian Americans is more closely tied to white supremacy and historic white nativist policies than the model minority myth. First coined and promulgated in the mid-1960s by white Americans, the term referred to Japanese and Chinese Americans, focusing obsessively on their seeming success in the face of discrimination. The model minority myth gets denounced on a regular basis lately, and many journalists, writers, and activists have analyzed and challenged the economic and class implications of the myth and the damage it does less privileged Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

No current narrative of Asian Americans is more closely tied to white supremacy and historic white nativist policies than the model minority myth. First coined and promulgated in the mid-1960s by white Americans, the term referred to Japanese and Chinese Americans, focusing obsessively on their seeming success in the face of discrimination. The model minority myth gets denounced on a regular basis lately, and many journalists, writers, and activists have analyzed and challenged the economic and class implications of the myth and the damage it does less privileged Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

But there’s another insidious side to the model minority myth that needs the same unpacking and deconstructing: the narrative of the quiet and obedient Asian – the one who works twice as hard and neither complains nor challenges authority. The myth was born at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, deliberately juxtaposing Asians against other racial minorities. It’s an image used not only to keep Asian Americans in their place but one that upholds white supremacy.

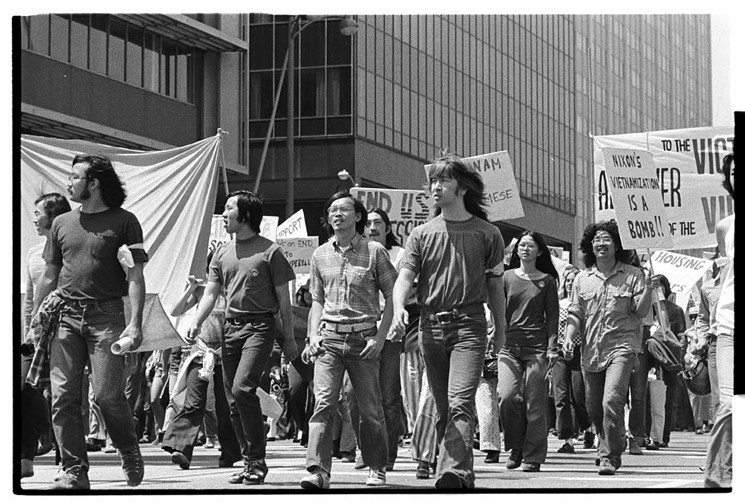

Our real history as Asians in America defies this false narrative. Asian American resistance to racism dates back to at least the 1800s. Imported to the U.S. as cheap labor to serve white economic interests in the “new world”, immigrants from China, Japan, India, and the Philippines built the transcontinental railroad opening up the western U.S., and worked sugar plantations and farms in Hawaii and on the Pacific Coast. Asian immigrants soon found themselves the target of hate violence and virulent anti-immigrant and racist laws, including those that barred Asians from accessing immigration and citizenship as well as that prohibited (explicitly or implicitly) everything from land ownership to voting to public education to interracial marriage. This would eventually culminate in the mass incarceration of 120,000 innocent individuals without due process.

Yet in the face of such hate, Asian immigrants did not meekly accept their fate. Instead, a number of Asian immigrants looked prejudice in the eye and refused to blink, challenging through the courts the laws they deemed unfair and unjust. Although not always immediately or obviously successful and not necessarily a direct attack on white supremacy per se, these cases were important in that they did directly challenge the whites in social and political power at the time. Some cases went further, paving the way to eventually overturn discriminatory policies or even leading to landmark decisions affecting not only Asians but other communities of color.

Resisting the Chinese Exclusion Act and anti-Chinese discrimination

Starting in the late 1800s, Asians were banned for decades from entering the U.S. by the Chinese Exclusion Act and other immigration laws. Chinese immigrants at the time brought a number of legal cases including several that reached the U.S. Supreme Court. Although they did not always succeed (e.g., many direct challenges to exclusion such asChae Chan Ping v. U.S. failed), these cases demonstrate that Chinese immigrants of the late 1800s and early 1900s did not passively accept the Exclusion Act and related discriminatory laws. And although the Exclusion Act itself was not repealed until the mid-1900s, some early cases did have a lasting impact in establishing legal protections for non-citizens in the U.S. For example,Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886) established that the 14th Amendment applied to Chinese immigrants, andWing Wong v. U.S. (1896) determined that the same constitutional protections extend to non-citizens as citizens in criminal cases.

Redefining U.S. citizenship

From the nation’s founding through the 1950s, the United States limited citizenship — and its many privileges such as voting and land ownership — to “free white persons”. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, in addition to banning new immigrants, also explicitly barred Chinese immigrants already in the U.S. from becoming U.S. citizens.

A number of Asian immigrants challenged these laws. The most important case was brought by Wong Kim Ark, who was born in the U.S. but, after a trip to China, was denied re-entry to the United States on the grounds that the son of a Chinese national could never be a U.S. citizen. Wong disagreed – and sued the federal government, resulting in the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1898 decision defining “birthright citizenship” – that children born in the United States, even to parents not eligible to become citizens, were nonetheless citizens themselves under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Wong successfully challenged a law designed to preserve white supremacy, and in doing so, he shaped the uniquely diverse character of our nation, by giving root to countless immigrant communities from all races and nationalities.

Other Asian immigrants also sought U.S. citizenship by challenging the definition of “free white person”. In back-to-back cases that reached the U.S. Supreme Court in the early 1920s, a Japanese immigrant (Takao Ozawa v. U.S.) and an Indian immigrant (U.S. v. Bhagat Singh Thind) respectively argued that they should be allowed to naturalize as a “free white person”. The Supreme Court ruled against both men, holding fast to the definition of “white” as both Caucasian and light-skinned (thus excluding Mr. Thind, whom the Court acknowledged was literally Caucasian by virtue of his birth in the Caucasus mountains, if not for the purposes of US citizenship), but their cases laid the groundwork for the eventual elimination in 1952 of the racial requirement to naturalize.

Challenging anti-miscegenation laws

Most anti-miscegenation laws at the turn of the 20th century blocked interracial marriages between whites and African Americans, but marriage between whites and Asians (“Mongolians” and “Malays,” at the time) was also barred, starting in states with significant Asian populations such as California and Washington but expanding to 15 states across the country by 1950.

In one California case, a Filipino man argued that as a “Malay” and not a “Mongolian”, the state law barring marriage between whites and Mongolians did not apply to him. The court agreed, but not surprisingly the state immediately amended the statute to explicitly bar “Malays” as well, preserving the white supremacy that gave rise to anti-miscegenation laws in the first place. But the fight against anti-miscegenation was a matter of survival in that era. Asian men comprised the vast majority of the low-wage laborers brought from Asia to the U.S. during this time, and with Asian women largely barred from legally entering the country, Asian men pushed back against anti-miscegenation restrictions as they sought to build families and communities.

Fighting for access to education

Although new immigrants were barred by the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, by that time cities like San Francisco had developed a small Chinese community, despite virulently anti-Chinese political leadership. In 1884, a Chinese immigrant mother tried to enroll her daughter, Mamie Tape, in the neighborhood elementary school, but the little girl was denied entry. The family sued, alleging violations of state and federal law. The California Supreme Court agreed with the Tapes, giving Chinese immigrants a right to public education in California, although it was a “flawed victory” in that racist education and political leaders created segregated schools for Chinese children that lasted for decades.

Nearly 100 years later, the San Francisco school system was desegregated by court order, and Chinese immigrant families fought a new legal battle over public education. After desegregation, thousands of Chinese immigrant students not fluent in English found themselves shut out of a meaningful education because the school district failed to provide them appropriate assistance, and instead placed some students in special education classes while forcing others to repeat the same grade for years. The families of Kinney Kinmon Lau and other Chinese students filed a civil rights lawsuit against the San Francisco school district. In 1974, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Lau v. Nichols that the school district had violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Lau decision had a significant legacy, both in shaping bilingual education in the U.S. for many years as well as clarifying that disparate impact discrimination (discriminatory in impact) violated the Civil Rights Act.

Challenging constitutionality of “Japanese American internment”

Perhaps the best-known, explicitly anti-Asian act by the U.S. government was the mass incarceration during World War II of 120,000 Japanese Americans, mostly U.S. citizens. A number of Japanese Americans – notably Minoru Yasui, Gordon Hirabayshi, Mitsuye Endo, and Fred Korematsu – challenged the incarceration as unconstitutional. Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against them at the time, individual convictions against HIrabayshi and Korematsu were later thrown out in the 1980s. While the Supreme Court has not yet explicitly overruled the broad power of the federal government during times of war, the legal challenges by Yasui, Hirabyashi, Endo, and Korematsu have led over time to acknowledgment by the federal government that it committed a grave civil liberties error in imprisoning Japanese Americans en masse and these cases continue to have deep implications today during an era of rampant profiling of Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim and South Asian communities.

* * *

Ours is a history of resistance, and we can learn from earlier Asian Americans who defiantly “rocked the boat” and succeeded against all odds. But we must also deepen the battle we as Asian Americans wage against those that hold political and social power in this country.

As we face a current administration that prizes blind obedience to those in power and embraces white nativism, we must not only fight back against racism that impacts our communities, we must fight the battles that loom ahead — over family immigration, border enforcement, affirmative action — with a goal of dismantling the very white supremacy that drives those policies in the first place.

Karin Wang is a Los Angeles-based advocate for a more just and equitable world. She is the new Executive Director of the public interest law program at UCLA School of Law. Previously, she served for more than 15 years as Vice President of Programs and Communications at Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Los Angeles, where she worked on immigrant rights, language rights, racial justice, and LGBTQ equity issues.

Write Back, Fight Back(#WriteBackFightBack) is a weekly essay series sponsored by 18MillionRising, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, and Reappropriate. It features emerging Asian American writers on topics of racial and social justice. This is the final essay of the series.