By Guest Contributor: Heath Wong

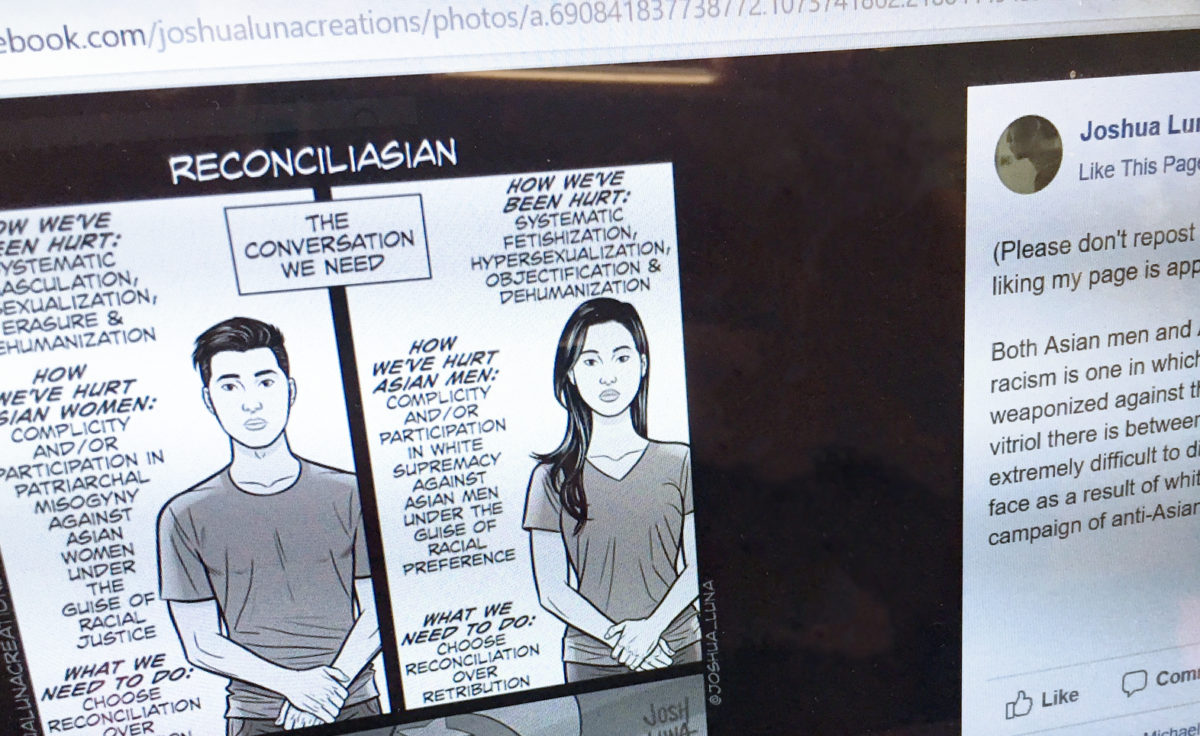

Editor’s Note: Earlier this month, artist Joshua Luna published a web comic titled “Reconciliasian” addressing gender relations in the Asian American community. This post is a response to that comic.

I deeply respect Joshua Luna as an artist and as an activist. But, I find the framing of his latest comic – Reconciliasian – problematic. The comic juxtaposes two panels: one depicting an Asian man and the other depicting an Asian woman. Next to each character, Luna lists the way each has “been hurt” (for Asian men, systemic emasculation and desexualization; for Asian women, systemic fetishization and hypersexualization), and how they’ve “hurt” the other. Luna laments how Asian men display “complicity and/or participation in patriarchal misogyny against Asian women under the guise of racial justice”; Asian women, says Luna, are guilty of “complicity and/or participation in white supremacy against Asian men under the guise of racial preference.” Luna concludes that both Asian men and Asian American women should “choose reconciliation over retribution.”

By the very nature of the symmetrical dichotomy presented by the comic’s layout, Luna implies equivalency. That apparent premise – that Asian women and men suffer equally and have also hurt each other equally, if in different ways – is used to argue that we must reconcile with each other to resist our true enemy.

The problem with that premise is that the equivalency depicted in the comic is false.

Patriarchal intraracial misogyny inflicted by Asian men on Asian women is far more harmful than any amount by which Asian women might reinforce racist desirability politics. The framework created by pre-existing systems of patriarchy that empower men by disempowering women and other marginalized genders means that there is simply no meaningful comparison that can be made.

Bluntly put: given patriarchy, Asian women don’t have the same societal capacity to hurt Asian men that Asian men do to hurt Asian women. That’s not to say that the capacity isn’t there; but, the power differential between Asian men and women is significant. Any conversation on the topic of gender relationships in the Asian community must account for this power differential.

Yes, Asian women can promote forms of white supremacist rhetoric. But, they cannot do so with a power unique to them. Asian American proximity to white supremacy – and any power derived thereby – is not unique to any gender; all Asian Americans (regardless of gender identity) must push back against the ways that white supremacy might recruit us into complicity with it.

For that matter, the equivalency presented by this comic fails a simple statistical analysis. Any complicity in white supremacist desirability standards is not widespread enough among Asian-American women to warrant this framing. In fact, Asian women are more likely to be in relationships with Asian men than with any other racial group. The vast majority of Asian women do not participate in the sorts of behavior – i.e. exhibiting a racial preference for non-Asian men in their dating lives – that are described in the “how we hurt Asian men” section of Luna’s comic. Thus, that which Asian women are accused of perpetuating is nowhere near a systemic problem. However, in a society built upon patriarchy, all men are conditioned by toxic masculinity’s misogynistic logic, and we must do the work of unlearning it. Patriarchy is a systemic problem.

While it might be inevitable to touch upon sexual desirability in a discussion of gendered racial politics, the comic’s primary focus on it is questionable. Desexualization of Asian men absolutely must be discussed and resisted; but, there’s an unfortunate trend among some Asian male activists that would place laser-focus attention solely on who wants to sleep with us and who doesn’t. That’s not exactly an ideal starting point — even if we put aside the manner in which society’s definition of things like “emasculation” tends be influenced by homophobia and similar forms of tacit prejudice. Centering one’s anti-racist activism on one’s own sexual or romantic frustrations is dangerously likely to result in a warped worldview, where being personally seen as “sexy” takes a higher priority than achieving more meaningful social change. (It’s also strange that Luna lists “erasure” as being a form of harm that Asian men have experienced, but not women. Asian women have clearly experienced significant political erasure that this comic fails to address.)

To his credit, Luna does point out in his caption that patriarchal violence exists even without the presence of white supremacy. But, that sentiment is not found within the comic itself. It further begs the question of why the final panel appears to posit that gender politics within the Asian American community are merely a byproduct of the white man trying to keep us divided.

Perhaps the point I’m most critical of is this: I dispute the comic’s assertion that “the conversation we get” (specifically with regard to Asian women in modern feminist circles) is about women wanting “retribution” against men, and that what we need is instead cordial reconciliation. In my opinion, this is a strawman. Generally speaking, what modern Asian feminists want from Asian men is responsibility, accountability, self-awareness of the ways in which we inflict harm, and a concerted effort to do better. Misandrist vindictiveness is not a meaningful presence among Asian or Asian American feminists; and even if it was, it wouldn’t be equivalent to patriarchal oppression.

So, what do I think we need? I think we need to be more socially responsible and aware as Asian men, and we must be willing to hold each other accountable. I think we need to have the wisdom to recognize what a significant problem is, and what it isn’t. I think we need to be able to look at an issue and recognize it as being an inherently lopsided beast, not just “two sides of the same coin.” I think we need to center the voices of the most marginalized among us, which means cis men need to take a seat when necessary.

I respect Luna and I enjoy his work. I think that the points he makes in the left-hand side of his comic are fairly apt, but in my estimation, the right-hand side could use some work.

Heath Wong is a 20-something Chinese-American writer based in New York. His purview includes race, gender, and culture in the modern age.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest contributor program and submit your own writing here.