By Guest Contributor: Sudip Bhattacharya

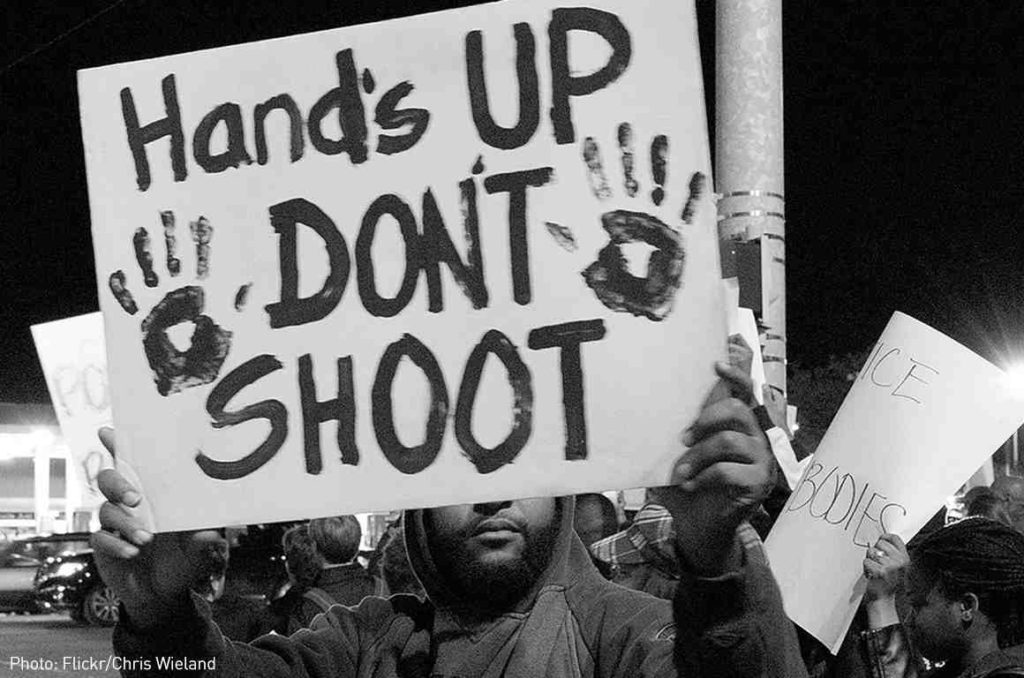

The acquittal of police officer, Betty Shelby, in the shooting death of Terence Crutcher was preordained.

The narrative follows a familiar pattern: A White individual (Shelby) encounters an unarmed African American man, and with no evident motive, chooses to end the life of the Black person standing before them.

“Crutcher’s death is his fault,” she later said. It is hard to imagine how that could be the case. Dashcam video shows that Crutcher was shot and killed while unarmed and complying with police orders.

After my visit to Ferguson last summer, I referenced the writings of Simone Browne, Christina Sharpe, and Alexander G. Weheliye, to argue that unless we understand how Anti-Blackness/Whiteness operate in the U.S., we will consistently fail in creating a society that would treat everyone with dignity and respect. Without this understanding, we will never build a place that honors the hopes and dreams of someone like Terence Crutcher.

THE FORMATION OF ANTI-BLACKNESS/WHITENESS

In 1790, only a “’free white person,’ could apply for citizenship, so long as he or she lived in the United States for at least two years, and in the state where the application was filed for at least a year,” deliberately excluding “indentured servants, free blacks and slaves, who were regarded as ‘property’ and not ‘persons.’”

In Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class, David Roediger highlights how those defined as “White” distanced themselves from what was associated as Black. For instance, White domestic servants refused to call their employers “masters” since it echoed the relationship of Blacks to slaveholders. Similarly, once industrialization started, White workers would only refer to their employers as “boss.”

“The idea of racializing assemblages, in contrast, construes race not as a biological or cultural classification but as a set of sociopolitical processes that discipline humanity into full humans, not-quite-humans, and nonhumans,” writes Weheliye in Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human.

Even after Emancipation, many Americans sought to preserve their Whiteness. “[…A] determined psychology of caste was built up. In every possible way it was impressed and advertised that the white was superior and the Negro an inferior race,” W.E.B. Du Bois observed in Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880.

Therefore, the more distance a White person can create between themselves and Blackness, the they can claim “Whiteness” and gain access to full legal rights.

A prime example of this is expressed through the experiences of Irish immigrants. Fighting for acceptance, most Irish Americans joined the Democratic Party (which was known as the White man’s party) and participated in race riots against African Americans. Roediger writes, “One obvious reason that the Irish focused so much more forcefully on their sporadic labor competition with Blacks than on their protracted competition with other whites was that Blacks were so much less able to strike back, through either direct action or political action. As Kerby Miller has argued, Irish Catholic immigrants quickly learned that Blacks in America could be ‘despised with impunity.’”

Other ethnic European immigrants did the same, learning that to be defined as American (and thus human), one must reject any possible political association with Blackness. And even as civil rights were won, Blackness remained a symbol of a “defunct” American and inhumanity for mainstream American politics.

Martin Gilens concludes in Why Americans Hate Welfare that “the overrepresentation of blacks among the poor is found in coverage of most poverty topics and appears during most of the past three decades,” adding, “[…] the stereotype of the lazy black has been a staple of our culture for centuries and its reflection in contemporary news coverage of poverty is only one current manifestation of this long-held belief.”

“Nearly half of Trump’s supporters described African Americans as more ‘violent’ than whites. The same proportion described African Americans as more ‘criminal’ than whites, while 40 percent described them as more ‘lazy’ than whites,” Reuters reported. “In smaller, but still significant, numbers, Clinton backers also viewed blacks more critically than whites with regard to certain personality traits.”

ANTI-BLACKNESS IN THE MODERN ERA

By centering Anti-Blackness/Whiteness, we can explain the current political and social climate we are in. As mentioned earlier, I am indebted to the brave minds of Browne, Sharpe, and Weheliye, whose theories have provided me the language to conceive of the following three points on how and why Anti-Blackness should be a major concern for anyone invested in comprehending our current social problems.

1. By centering Anti-Blackness in our political discussions, we learn how and why bodies are spared extreme mental and physical violence.

A person who wants to be included in the American Dream no longer needs to express obvious Anti-Black racism. However, he or she still needs to accept the dialect of bourgeois Whiteness, i.e. that a home in the suburbs is the pinnacle of success, and that hard work and determination make America what it is. The more one conforms to this bootstrapping narrative of American success, and the less one is inclined to break from that discourse, the more likely the individual is granted American political citizenship.

In a speech for The Asian Law Center (excerpted from Where Is Your Body?: And Other Essays on Race, Gender and the Law), Mari Matsuda pondered, “Is there a racial equivalent of the economic bourgeoisie? I fear there may be, and I fear it may be us.”

Matsuda feared that Asian Americans were adopting values that matched the interests of white America. In a Pew study, Asian Americans hold a “pervasive belief in the rewards of hard work” and that “nearly seven-in-ten (69%) say people can get ahead if they are willing to work hard, a view shared by a somewhat smaller share of the American public as a whole (58%).” Obviously, it is reductive to characterize all Asian Americans generally in the same way, since there are subgroups who confront enormous challenges; but this should not absolve the group from its overall advantages and opportunities from conforming to the White Gaze.

2. Anti-Blackness explains why African Americans are negatively affected, regardless of their economic class.

Whether one considers the mass incarceration rate (The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander) or segregation in the modern era (American Apartheid by Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton), African Americans are negatively affected at a more intense level compared to other groups of color and White Americans.

The Washington Post reported that “a poor black family, in short, is much more likely than a poor white one to live in a neighborhood where many other families are poor, too, creating what sociologists call the ‘double burden’ of poverty.” Survey of University of California-Los Angeles applicants found that the quality of high schools accessible to wealthy Black applicants were less favorable than that of high schools accessible to low-income White and Asian applicants. In a study, “researchers found that black graduates of elite universities such as Harvard, Stanford, and Duke were as likely to get responses from employers than white graduates of much less prestigious state colleges, such as University of California, Riverside, the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and University of North Carolina, Greensboro.” Overall, “upwardly mobile and middle-class blacks face difficulties others do not, such as discrimination in job search, hiring, and promotion and worse terms for home mortgages, making it challenging to sustain their status.”

By centering Anti-Blackness/Whiteness we can begin to comprehend why a young man such as Trayvon Martin or a boy named Tamir Rice were murdered when neither of them were from the “underclass”, and neither were behaving in ways that would be accepted for their age if they were from a non-Black community.

3. Finally, it offers a more comprehensive perspective on why our society has been less egalitarian.

Simone Browne writes in Dark Matters: On The Surveillance of Blackness, “The historical formation of surveillance is not outside the historical formation of slavery.” Browne discusses how surveillance of Black bodies led us to the current moment wherein individuals are tracked in the name of security and wherein certain individuals face heightened scrutiny at airports and border crossings. If Blackness is our lens, then one can easily see how certain people were always “branded” as Other, and defined as threatening the social order.

Loic Wacquant writes in “Crafting the Neoliberal State” that “a central ideological tenet of neoliberalism is that it entails the coming of ‘small government’: the shrinking of the allegedly flaccid and overgrown Keynesian welfare state and its makeover into a lean and nimble workfare state […].” Our government has ceded responsibility of caring for its citizens to the private sector. Yet, what Wacquant and others fail to see, similar to those who believe we’re living in an age of surveillance, that the current economic culture we are in, where governments and corporations work together to create more wealth for some while excluding others, is not new. Rather, these policies are a continuation of the past, especially when considering how Black bodies were always excluded from social programs due to the cruel logic that welfare would create “dependency.” Essentially, the elites were always searching for ways to limit the growth of social programs, and to maintain a hierarchy where some would be kept at the bottom.

Even during the New Deal, the federal government maintained this overarching ideology. “At the center of the New Deal’s instability was the missing place for the most forgotten ‘forgotten man’: the African American people,” Jefferson Cowie details in The Great Exception: The New Deal & The Limits of American Politics. “Well into the industrial age, the legacy of slavery in the United States still crippled the advance of modern politics. So entrenched was Jim Crow politics that had the New Deal been committed to racial equality, had it actually made any efforts to shatter the white consensus on black racial inferiority, it is most likely that the New Deal would not have happened.”

When attempts were made for moderate reform, the preservation of Anti-Black/Whiteness ideology prevailed. Cowie states, “The integration of schools through federally mandated busing ‘fell like an axe’ through the Democratic Party. Affirmative action on the job—in a period of high unemployment—helped push Northern white working-class voters to the right. Cartoonish rhetoric proliferated—for example, the suggestion that working peoples’ taxes were being pipelined directly to black welfare recipients, a racist fantasy catalyzed by Reagan’s Cadillac-driving ‘welfare queen’ stories, which helped many people justify pulling the Republican lever for the first time in generations of their families’ histories.”

The government and the people are complicit in the perpetuation of the status quo, and they have always been cunning in determining who deserved social programs and who didn’t. The only difference now is that this damning logic has expanded, and it now attributes traits historically linked to Blackness (i.e. laziness and fiscal irresponsibility) to others as well.

DISMANTLING ANTI-BLACKNESS/WHITENESS

In her searing account of how Black bodies are molded, Christina Sharpe writes in In The Wake: On Blackness and Being: “In what I am calling the weather, anti-blackness is pervasive as climate. The weather necessitates changeability and improvisation; it is the atmospheric condition of time and place; it produces new ecologies.” Sharpe argues that Black bodies experience a world with the heightened sense they might die at any moment, for doing absolutely anything. Echoing Fanon, she views it as a life trapped by the White Gaze.

Therefore, it is a daunting task to somehow deconstruct a negative force as powerful and as permeating as Anti-Blackness/Whiteness. Still, there are small steps that can be taken, such as boycotting businesses that traffic in Anti-Black behavior, or participating in organizations that challenge the Whiteness of its members rather than tiptoe around the issue.

However, the most important action we might take — especially for non-Black POC and those with economic and educational privileges — is to listen and elevate the voices of the marginalized, especially in areas oppressed by Anti-Blackness/Whiteness.

This is a technique born out of the effort of academics such as Patricia Hill Collins, who in her work as sociologist, relies on the voices of African American women, from their literature, poems, and daily insights. “By emphasizing the power of self-definition and the necessity of a free mind, Black feminist thought speaks to the importance that African-American women thinkers place on consciousness as a sphere of freedom,” Collins shares in Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment.

As South Asian Americans, my friend and I decided to visit Ferguson about a year ago. Our goal was to understand beyond what was allegedly reported by the media. We spent two days talking with residents and exploring, trying to grasp the frustration and despair — but also, the defiance — within the community.

At one point, I came across the plaque pressed into the sidewalk and honoring Michael Brown. “I would like the memory of Michael Brown to be a happy one,” it read. “He left an afterglow of smiles and when life was done. He leaves an echo whispering softly down the ways, of happy and loving times and bright and sunny days. He’d like the tears of those who grieve, to dry before the sun of happy memories that he left behind when life was done.”

Sudip Bhattacharya is a PhD student in Political Science at Rutgers University. He’s also a journalist and writer whose work has been published in CNN, Lancaster Newspaper, The Daily Gazette, The Jersey Journal, The Washington City Paper, The Aerogram, and AsAm news. He mostly focuses on issues of social justice, race, and identity through his work, and is a fervent optimist, but not the annoying kind.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest contributor program and submit your own writing here.