I hate to be that person but I think it’s time we set the record straight, especially since a bunch of journalists are already speculating about the impact(s) of pro-Peter Liang protests on the outcome of today’s hearing: This year’s pro-Liang protests marches are neither the first, nor the largest, nor the most impactful protest movements organized by the Asian American community.

Let me be clear: I do not mean to dismiss the achievement of this year’s pro-Liang protests. It is never easy to organize a nationwide demonstration, never mind one that is able to attract 15,000 in a single city and thousands more nationwide. I may not agree (like, at all) with Liang’s supporters, but no one can or should scoff at the community organizing work it took to make these protests materialize. And, quite clearly, these protests, letter writing campaigns, and online petitions had an impact: after DA Ken Thompson said he would not seek prison time for Liang, Judge Danny Chun today reduced Liang’s conviction to a lesser charge before sentencing him to 5 years probation and 800 hours community service for his killing of Akai Gurley.

Liang’s supporters will be celebrating today. But, in the interest of an accurate representation of AAPI history, those celebrations must be presented alongside an honest contextualization of AAPI’s long history of vociferous protest movements.

Many of Liang’s supporters have expressed their belief that this year’s pro-Liang rallies are the largest or most impactful protest marches ever organized out of the AAPI community. My Facebook is rife with such statements from Liang’s supporters, and they are as galvanizing a sentiment as they are untrue.

Nonetheless, this talking point is so oft-repeated that it has permeated into mainstream media, where it has become unintentionally legitimized through the writing of many including Jay Caspian Kang — a thoughtful journalist whose work I deeply respect — in a well-cited essay for the New York Times. In that piece, Kang called the Liang protests “the most pivotal moment in the Asian-American community since the Rodney King riots.” In an interview with NPR today, Kang elaborated saying: “It’s rare to see Asian Americans protest anything… We don’t quite have a language of protest. There’s no real written history of Asian American protest in the United States.” Kang went on to say that outside of the fight for reparations following Japanese American incarceration, most would struggle to find an instance of an Asian American protest movement because most were either “ignored” or “very small.”

Readers and listeners of a narrative like this might be lead to believe that the AAPI community is largely politically passive, and that we have rarely organized any large-scale protest movement that has brought about any sort of significant change; or, readers might assume that if such protests ever took place, a written record of those events does not exist rendering them inconsequential to time. Yet, a quick perusal of my bookshelf offers a compelling counter-narrative. In fact, one finds many instances of massive rallies and protest marches organized out of our community drawing tens of thousands of AAPI protesters.

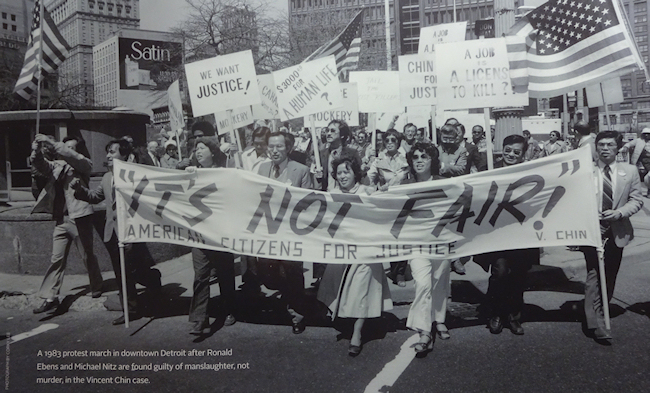

We can draw from throughout AAPI history for examples. Most of us easily remember the nationwide protests that repeatedly attracted tens of thousands of Asian Americans to march in the streets in multiple cities across the country for justice for Vincent Chin. Outraged that Chin’s killers would receive no jail time and only a $3000 fine for the commission of a hate-motivated murder, Asian Americans were spurred to action in the 1980’s. But these protests were, by no means, the only massive protest marches organized by the AAPI community.

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, Asian American agricultural workers (including Chinese, Japanese and Korean labourers) repeatedly engaged in strikes for better wages and working conditions. In just one example documented by Ron Takaki in Strangers From a Different Shore, 8,000 predominantly Japanese American farm workers organized a series of twenty strikes on the plantations of Hawaii, an incident of particular significance because Hawaii was home to only 60,000 Japanese people total in that year. In case you’re struggling with that math, a whopping 14% of Hawaii’s total population of Japanese people united in protest and walked off the job in 1900.

Seventy years later, the modern labour movement was indelibly impacted by the success of the 1965 Delano grape strike, which was initiated by Filipino American table grape growers under the banner of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee. Led by Filipino American labour leaders Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, AWOC joined forces with Cesar Chavez’s National Farmworkers’ Association to form the United Farm Workers (UFW), which launched years of protest marches, boycotts and non-violent demonstrations that eventually won better wages for 10,000 of the country’s lowest-paid agricultural workers.

Twenty years after the Delano grape protests, 20,000 Chinatown garment workers — most of them Chinese American women — joined forces to walk off the job demanding a fair contract with their employers. They won a new contract within hours, and according to Cornell University left a lasting impact on the IGLWU union and NYC’s Chinatown.

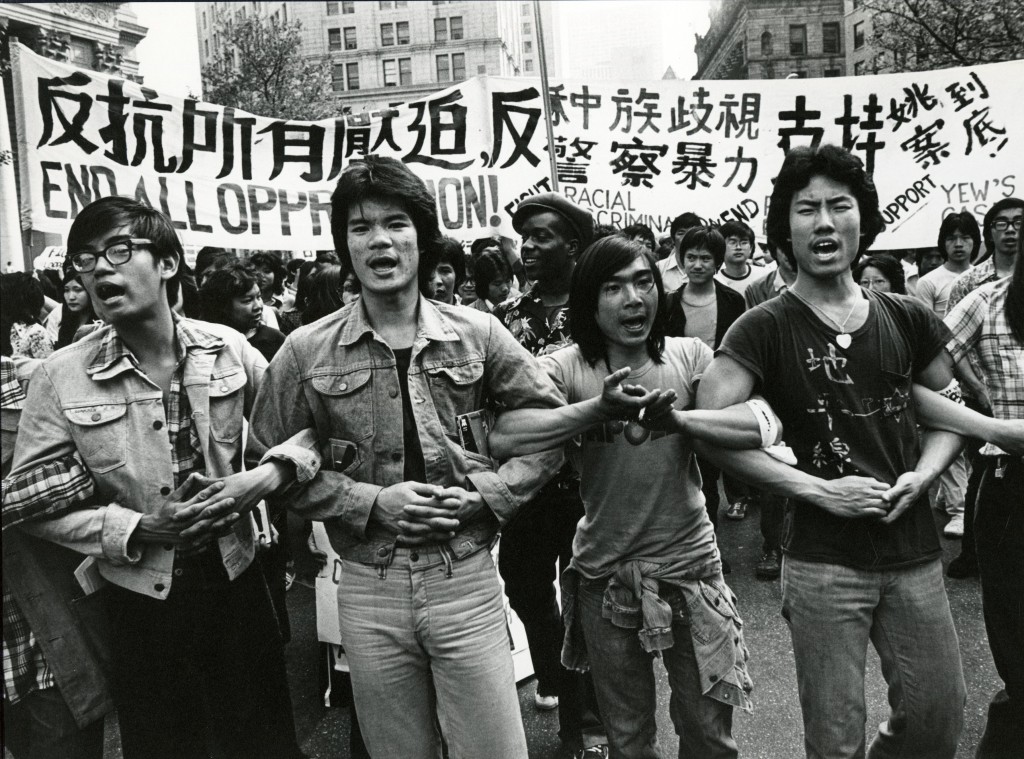

Labour rights are not the only issue that has galvanized the AAPI community. In fact, the Peter Liang rallies are not even the largest New York City-area rallies to attract predominantly Asian American protesters on the topic of excessive police force. In 1975, 20,000 Asian Americans took to the streets in New York City demanding justice in the suspected racial profiling and excessively brutal police beating of 27-year-old Chinese American architect Peter Yew during a routine traffic stop.

The difference, of course, is that in 1975, Chinese Americans were marching to end the excessive policing of communities of colour, not in defense of it.

We could go on, and on, and on citing AAPI protest movements — large and small — that have made a massive difference to the course of American and AAPI history. We could talk about I-Wor-Kuen and other Asian American radicals of the 1960’s. We could talk about the decades of student protests for AAPI Studies that continue to shake the Ivory Tower, resulting in numerous victories for ethnic studies programs over the years. We could mention this past year’s Thirty Meter Telescope protests, which successfully blocked desecration of land considered sacred by Native Hawaiians. We might note the nationwide coordinated protests of AAPI students against Abercrombie & Fitch stores in the early 2000’s, remarkable for being one of the nation’s first examples of activists using digital tools to facilitate on-the-ground community organizing.

We might even expand our definition of “protest movements” to include large-scale acts of resistance organized by the AAPI community that employ digital tools — themselves an equally legitimate form of activism — rather than the more conventional street rally. If we were to consider also the politicized congregation of AAPIs on the streets of social media, we would find even more numerous examples in recent memory of progressive (and conservative) AAPIs agitating for change. We might remember, for example, the outcry from thousands of Japanese Americans around the country that single-handedly halted the sale of incarceration artifacts last year. Alongside that campaign, we might find countless digital protest movements that range in topics from media representation to affirmative action, and from environmental justice to reproductive rights — all occurring well within recent memory and many still ongoing.

Hopefully the point becomes clear: AAPIs have never been bystanders to social justice. This year’s impassioned rallies organized by some Chinese Americans might be politically notable, but they are not historically exceptional. AAPI’s have a long history of protest movements, and the written record of that resistance exists. Ignorance or erasure of that history by the mainstream does not occur because AAPI revolutionaries are irrelevant. Rather, I would venture that (in addition to mainstream ignorance of AAPI history) stories of the meek and generally apolitical Asian American compel for their implicit reinforcement of the Model Minority Myth.

This is also why it is imperative that this narrative be immediately and thoroughly dismantled.

The AAPI community cannot afford to forget our roots. After all, as Ron Takaki says: “All memory is political.” Contrary to model minority stereotypes, ours is a proud history of resistance; one that deserves better than being overlooked, ignored, or erased.

Update (4/20/16): This post has received minor restructuring and additional writing because it was originally written and published at 3AM in the morning and I was apparently punchy.