The theatre world is embroiled in controversy right now over the attempted White-washing by Clarion University of Lloyd Suh’s cutting-edge play, “Jesus In India”.

Suh’s play — an irreverent exploration of popular conceptions and misconceptions of historical religious figures — includes several characters of Indian descent. However, when Professor of Theatre at Clarion University Marilouise Michel decided she wanted to put on a student production of the play this year, she seized upon a quip by Suh in one of the play’s liner notes (wherein he describes the play’s appeal as “universal”) and interpreted it as license to cast non-South Asian actors as characters named “Gopal”, “Mahari”, and “Sushil”. Michel also decided to make dramatic rewrites to the play (which originally contained only two or three songs). She commissioned a full songbook, transforming the play into a musical.

All public productions of copyrighted plays such as “Jesus in India” can only be put on following a licensing agreement with the play’s owner, and often this document stipulates that significant changes to the play’s title, text, or stage directions require pre-approval. Writes the Dramatist’s Guild in an open letter today:

Playwrights own our material. We are protected by copyright; in fact, we have sacrificed a great deal for the privilege of authorial ownership, most notably the right to unionize. We have foregone equitable compensation, health and pension benefits, and the right to collectively bargain. But in doing so, we have retained the hard-won right to protect the integrity of our work. This includes approval of all creative elements, including the cast.

Play licenses clearly state that “no changes to the play, including text, title and stage directions are permitted without the approval of the author” or words to that effect. Casting is an implicit part of the stage directions; to pretend otherwise is disingenuous.

Directors who wish to dramatically reimagine material can choose from work in the public domain. But when a play is still under copyright, directors must seek permission if they are going to make changes to the play, including casting a character outside his or her obvious race, gender or implicit characteristics. To do so without meaningful consultation with the writer is both a moral and a legal breach.

Suh said in a statement posted to his social media that he was not made aware of Clarion University’s planned production of his play until weeks into rehearsal, when he discovered pictures posted to social media. It seems as if Michel was in talks with Suh’s agent, Beth Blickers, over the idea to transform the play into a musical but only received limited permission to do so as a classroom exercise. When Michel later decided to stage a public production (which was beyond the scope of the permissions she had received from Blickers), she stopped responding to Blickers’ questions regarding the musical adaptation or the play’s casting. Furthermore, a licensing agreement was initiated but never completed by Clarion University, meaning that Michel’s planned production — had it actually been staged — would have amounted to theft of copyrighted work.

Suh’s agent was given a $500 royalty check in the process of negotiations, which was prematurely cashed and which will be returned to Clarion University. However, it is standard practice for agents to deposit checks upon receipt (for later transfer to the playwright) even before licensing agreements have been finalized, and that it is senseless to treat this as a substitute for a signed agreement.

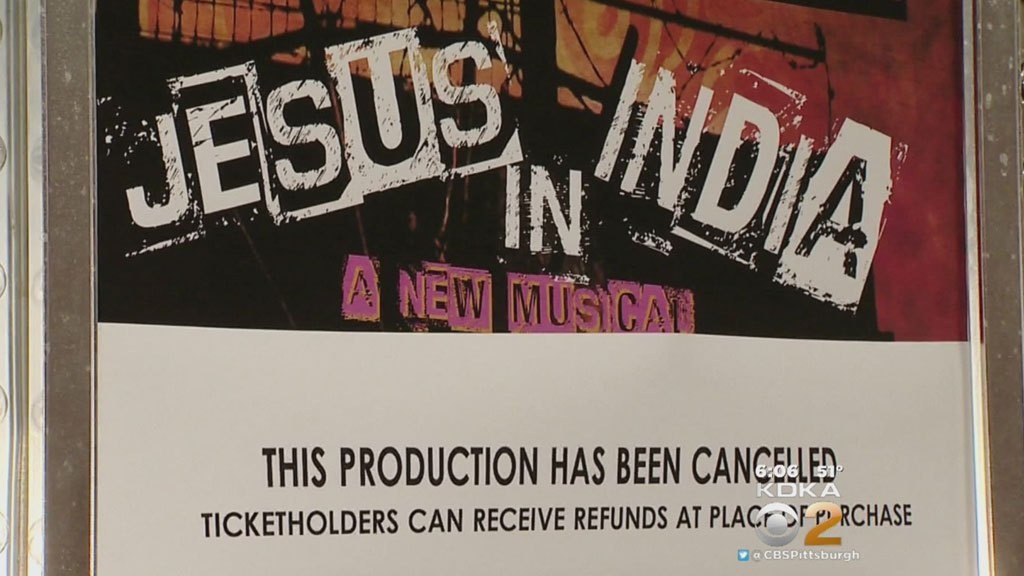

When Suh discovered pictures of Clarion University’s “Jesus in India” rehearsals, he contacted the school with his concerns and asked that the Indian roles be recast. Alternatively, he suggested that the production be cancelled. Clarion University chose the latter option, and put a stop to the planned show a week before opening night.

The announced cancellation of the play sparked outrage among hand-wringing theatre enthusiasts who — inexplicably — blame Lloyd Suh for not being more forgiving and open about a massive, unsanctioned violation of his work. Michel declared that “racial politics hurt my students” in an essay published on the Chronicle of Higher Education (wherein she also refuses to call Suh by name, repeatedly referring to him instead as the “Asian playwright”; Lloyd Suh is Korean American). Clarion University put it more bluntly, saying that the school’s students are being punished for being the “wrong skin color”.

Hardly.

The controversy conjures several other contemporary examples of White-washing in the casting of characters of colour (and seemingly in particular, Asian American characters): Several real-life Asian Americans were reimagined as White men and women in “21”. Emma Stone was cast in the role of a biracial Chinese American and Native Hawaiian woman in Cameron Crowe’s “Aloha”. Tilda Swinton will appear as the Ancient One, a Tibetan sorcerer, in the upcoming “Dr Strange” movie adaptation. Jake Gyllenhaal tried to convince us he was a “Prince of Persia”. Protagonists for M. Night Shyamalan’s “Last Airbender” movie were White-washed while villains were cast with greater fidelity to their characters’ apparent races.

In each case, White artists and audiences paint themselves as victims when they run afoul of basic common sense over race and casting. They demand to know why the “right actor” (which is, too often, is code for the “White actor”) can’t play any part, even though they would rarely raise such principled defenses of an actor of colour playing an explicitly White role. This is all grounded in an outrageous sense of White entitlement over communities of colour: over our racial identity, our creative works, and even our language of racial justice.

Michel even went so far as to appropriate the language of diversity initiatives, arguing that her decision to White-wash the play stemmed from a desire to “open up opportunities” for all students. The presumption she makes is that none of the Asian American students at Clarion University were qualified or interested in participating in her play, which is a line of argumentation typically used to suggest that underrepresented minority youth are less deserving for admission to our nations colleges and universities than their White counterparts. To invoke this argument to defend an act that eliminates — not creates — diversity at the school is appalling and offensive to those of us who are genuinely committed to creating opportunity for underrepresented minorities.

Suh is in the right here: he is only protecting the creative vision for his play — something we expect and praise in other artists. He refused to cave in to demands that he — a writer of colour — make amends for how others wanted to use (and perhaps abuse) the fruits of his labour. In an era when cross-racial casting (in either direction) is occurring with greater frequency, I strongly agree with Suh’s stance: we must recognize that — as in life — race is always a fundamental aspect of a character’s identity. Thus, racial cross-casting should never be engaged in lightly. Instead we must always seek out — and respect — the intent of the creator. Sometimes, creators give permission for racial cross-casting, as Stan Lee did for Michael B. Jordan’s Johnny Storm. But, even in this case (and in keeping with my initial apprehensions), Jordan’s casting was a fundamental alteration to the Storm character, albeit one that worked out well (“Fantastic Four” is really great; you should see it).

Here, Michel proceeded — like far too many other artists who seek to “adapt” the works of (or about) a person of colour — as if the only justification she needed was her presumptuousness over Suh’s work. Would she have been so irresponsible with the work of a White artist? Would the theatre community have been so quick and so vitriolic in their efforts to put Lloyd Suh “back in his place”? It’s hard to know for sure.

But one thing is certainly true: the victims here really are the students of Clarion University, whose work to put on “Jesus in India” is just the latest collateral damage of White entitlement.

Update (11/21/2015): The Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC) has issued the following statement, and urges supporters to tweet to #IStandWithLloydSuh.

We, the Steering Committee of the Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC), write this in support of Lloyd Suh regarding the recent controversy surrounding the cancellation of the production of his play, “Jesus in India”, at Clarion University.

The first and last reason to support Mr. Suh’s actions is that he acted on the right to which every playwright of every color, gender, culture, sexual orientation or physical ability is entitled according to the Dramatists Guild Bill of Rights and according to copyright law: that of ensuring their work is done how they wish it to be done, and that if those wishes are ignored, they may withhold the rights to said work. They should not have to defend a production that was attempted despite the producers’ failure to obtain the rights, no matter what reason they have for not granting them.

Over his years as a playwright, Mr. Suh has written many plays about the Asian and Asian American experience. In doing so, he has created many roles for our community, roles that we do not often see – leading roles, nuanced roles, roles in which ethnicity informs the character without creating conflict. In “Jesus in India,” again Mr. Suh created characters with a specific ethnic make-up. In casting white actors in the roles of Sushil and Gopal, Clarion claims that it has participated in “non-traditional casting”, a gross misinterpretation of the intended purpose of the concept. In fact, “non-traditional casting” (often more aptly referred to as “inclusive casting”) was never meant to give more opportunities to those who have historically had more of them, but to promote the elimination of exclusion in the theatre by casting Actors of color and Actors with disabilities in roles where race, ethnicity, gender, age, and/or presence or absence of a disability are not germane to the character. Clarion has, instead, participated in the whitewashing of Mr. Suh’s play, a practice that Mr. Suh himself cites in his letter to Clarion “is connected to a very painful history of egregious misrepresentation and invisibility, and is incredibly hurtful. Hurtful to a community for whom opportunity and visibility is critical, and also extremely hurtful to me personally as a flippant denial of Asian heritage as a relevant and valid component of one’s humanity.”

In light of detractors making claims that Mr. Suh has engaged in reverse racism, we encourage everyone to tweet, update and vocalize your viewpoint using the hashtag #IstandwithLloydSuh.