In the wake of the #AsianPrivilege response hash-tag to #NotYourAsianSidekick and #BlackPowerYellowPeril, it appears as if (among other misguided ideas) there is a prevailing notion out there that, in contrast to other minorities, Asian Americans “lack a history of resistance” (or that we think we do), and that this invisibility and dearth of civil rights history actually confers upon the Asian American community a form of racial privilege.

Putting aside the second half of that assertion regarding privilege for a minute, there’s one other major problem: any argument that relies upon the assumption that Asian Americans lack a history of resistance is patently ahistorical.

Like really, really, really wrong. Like insultingly wrong.

After the jump, here are 10 examples of Asian American’s history of oppression and political resistance.

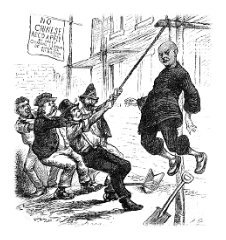

1. Over half a century of Chinese resistance against anti-Chinese purges and lynching in the West Coast (mid 1800’s through early 1900’s)

Frustratingly, few Americans — myself included, until my college years — are aware that 19th century anti-minority violence targeted Asians in addition to other minorities. Jean Pfaelzer’s Driven Out documents the untaught history of anti-Chinese lynching in California and the Pacific Northwest from 1848 to the twentieth century, and the Chinese community’s storied history of resistance. As California mounted an escalating institutional war against Chinese immigrants — including race-based taxes and anti-immigration legislation — White citizens took to the streets, razing Chinatowns and expelling and murdering Chinese migrants, by the tens and hundreds. From the book jacket: “Chinatowns across the West burned as Chinese miners and merchants, lumberjacks and field-workers, prostitutes and merchants’ wives were violently loaded onto railroad cars and steamers, marched out of town, or killed.”

One (of the many) examples: “In 1887, thirty-one Chinese miners are slaughtered in the ‘Snake River massacre’ at Hell’s Canyon along Oregon’s Columbia River; a gang of white farmers and schoolboys rob and murder the miners, mutilate their bodies, and throw them in the river.”

But contrary to the popular narrative of the unassuming Chinese migrant, “the Chinese fought back — with arms, strikes, and lawsuits and by flatly refusing to leave. When red posters urging the Chinese to refuse to carry photo identity cards appeared… more than one hundred thousand joined the largest mass civil disobedience to date in the United States.” The rest of the book provides detail of these acts of localized resistance (to varying degrees of success), chiefly through organized labour strikes and on occasion through armed force.

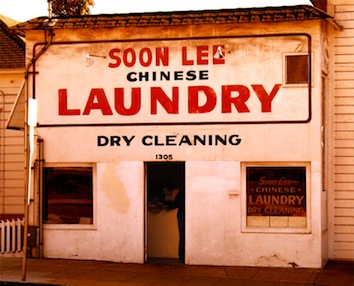

2. Civil disobedience and lawsuits resisting discriminatory laws: Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886)

Legal and cultural bias in the late 1800’s prevented many Chinese migrants in California from finding work; consequently, many turned to running laundries (stereotypically viewed as “women’s work” and thus disdainful for White laborers) as one of their few avenues for earning a living. In response, San Francisco penned an ostensibly race-neutral law requiring that all laundries not be operated in wooden buildings, a law that would in effect outlaw 95% of the city’s Chinese-owned laundry businesses and drive them out of the city. Yick Wo, who owned a laundry with a legal license for years prior to the passage of the ordinance, refused to close his laundry and further refused to pay the $10 fine; he was consequently imprisoned where he sued for a writ of habeas corpus.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favour of Yick Wo, deciding for the first time in American history that any law that in administration (if not explicitly in writing) that results in discrimination violates the Fourteenth Amendment. Although the law failed to be applied to reverse subsequent Jim Crow laws of the Deep South, it has been subsequently cited in over 150 Supreme Court cases. According to Pfaelzer, this case served as one of the legal precedents for many of the civil rights cases of the 1960’s.

3. Labor strikes and collective bargaining (late 1800’s to early 1900’s)

For most of our early history in the United States, Asian Americans lived in Hawaii and throughout parts of the West Coast, working on farms and plantations on subsistence wages or as indentured laborers. In the wake of Emancipation, plantation overseers were keenly aware of the possibility of labor revolt, and used many of the same tactics employed by slave-owners in the Deep South to keep Asian laborers under control — encouraging illiteracy and pitting workgroups against one another to maximize discord. Nonetheless, Asian workers of many ethnicities, including Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Filipino, organized some of the major strikes of the era.

Ron Takaki recounts in Strangers from a Different Shore:

The most important manifestation of ‘blood unionism’ [unions organized by ethnicity] was the Japanese strike of 1909. Protesting against the differential-wage system based on ethnicity, the strikers demanded higher wages and equal pay for equal work. They noted angrily how Portuguese laborers were paid $22.50 per month while Japanese laborers earned only eighteen dollars a month for the same kind of work. ‘The wage is a reward for services done,’ they argued, ‘and a just wage is that which compensates the laborer to the full value of the service rendered by him… If a laborer comes from Japan and he performs the same quantity of work of the same quality within the same period of time as those who hail from the opposite side of the world, what good reason is there to discriminate one as against the other? It is not the color of skin that grows cane in the field. It is labor that grows cane.’

The Japanese strikers struggled for four long months. The strike involved 7,000 Japanese plantation laborers on Oahu, and thousands of Japanese workers on the other islands supported their striking compatriots, sending them money and food.

Similar strikes were organized by Chinese, Korean, and Filipino-based unions, often either alone or between unions of different ethnicities or racial groups.

4. United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898)

In the 1800’s, non-White foreign-born migrants — including Asians — were disallowed from pursuing or obtaining American citizenship based exclusively on race and ethnicity; upon this federal law was built a host of other local and federal laws targeting anyone “ineligible for citizenship”, preventing them from purchasing land or even testifying in court in their own defense. Against this political landscape, Wong Kim Ark, a San Francisco-born son of Chinese immigrants, found himself barred from re-entry into the United States under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act after an overseas trip.

The Fourteenth Amendment had already been passed establishing American citizenship for “all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power”, however until Wong Kim Ark’s case, it was interpreted as not applying to Asian immigrants or their children (under the “foreign power” qualification). Instead, children of Chinese migrants were seen as inheriting the citizenship of their parents. Wong Kim Ark argued that under the Fourteenth Amendment, he was an American citizen based on his birth on U.S. soil; ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with him, broadly establishing for the first time in U.S. history the principle of jus soli, a notion derived from English common law which asserts that all citizens derive citizenship from the place of their birth.

The ramifications of the Wong Kim Ark decision on our contemporary notions of citizenship are undeniable.

5. The Chinese boycott of 1905 and other acts of resistance against exclusionary immigration laws. (1880’s – early 1900’s)

As mentioned above, the late 1800’s was marked by a series of racist exclusionary immigration laws that targeted Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Filipinos, and Asian Indians that essentially halted entry migrants from Asian countries for decades; the most famous of these laws is the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

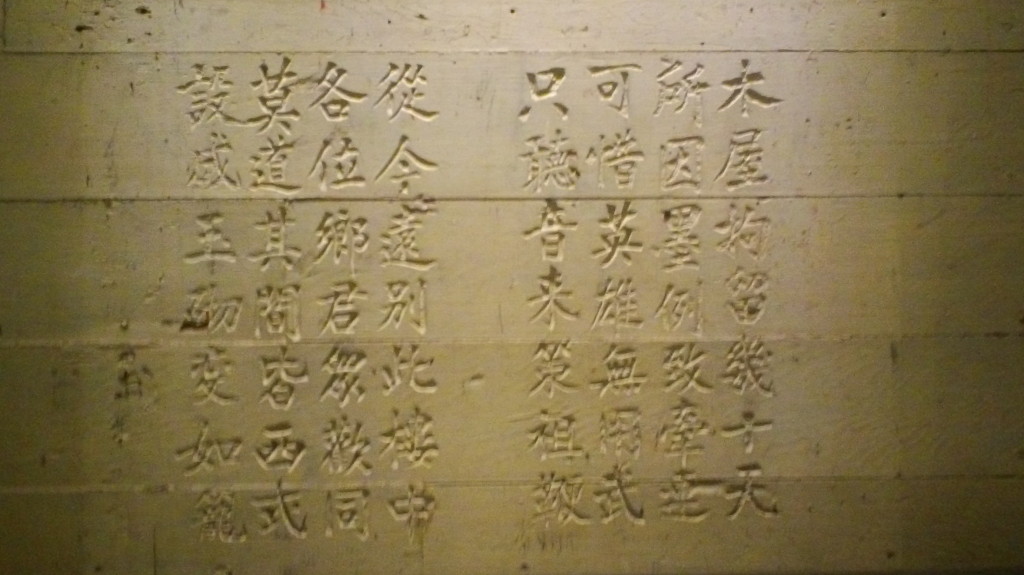

Lucy E. Salyer’s Laws Harsh as Tigers documents the “sophisticated and often-successful legal challenges to the enforcement of exclusionary immigration policies”. However one example of the failure of the legal system to overturn exclusionary and intolerant laws was in United States v. Ju Toy (1905) where the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed the right of port inspectors to make arguably arbitrary admittance decisions, and even subject potential immigrants to wildly inhumane treatment in the country’s immigration ports (those unaware of the conditions of Angel Island should read up on it). Writes Salyer:

In 1905, within days of the Supreme Court’s decision in Ju Toy, Chinese merchants once again took the offensive, this time turning to economic sanctions to protest American immigration policy. They helped to engineer a boycott of American goods in China…

The boycott brought the United States’ attention to bear upon the Bureau of Immigration’s methods. American merchants, worried that the boycott might ‘ultimately destroy American trade’ in the Chinese empire, joined in the demand that the agency treat exempt Chinese with greater respect and that it refrain from an overzealous enforcement of the laws. Other Americans became embarrassed by stories detailing the harsh methods of the immigration service.

Although a powerful example of Chinese Americans leveraging what economic power they could muster by reaching across the Pacific Ocean to China, the boycott was more symbolic than successful: it did not effectively overturn exclusionary immigration laws or improve conditions for Chinese Americans in America.

Another often-cited example of Chinese resistance to exclusionary immigration laws was the ‘paper son’ phenomenon, which is also well-documented in Salyer’s book.

6. Resistance to Japanese American Internment: Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu and the No-No Boys (1940s – 1990s)

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, Japanese nationals (remember, foreign-born migrants were not allowed to naturalize at the time) and domestic-born citizens were subjected to curfew and later were rounded up and detained in internment camps throughout America’s West Coast by Executive Order 9066. Contrary to popular opinion, however, many Japanese Americans resisted these racist efforts through whatever means available to them.

Gordon Hirabayashi, a college student at University of Washington, and Fred Korematsu, a welder living in California, refused to comply; Hirabayashi was arrested while Korematsu became a fugitive and went into hiding before being discovered and detained. Both subsequently challenged their convictions in court: the Korematsu case is largely interpreted as applying to relocation and internment, whereas Hirabayashi’s case focused on the constitutionality of the curfew.

For Japanese Americans who were interned, many of the men were forced to take an allegiance questionnaire applied to all internees in 1943, asking whether they would be willing to serve the US Army and foresake allegiance to Japan. For many internees, neither question was rational. Regarding the first question, it was unclear whether a “yes” answer would ensure draft into the war; for others, they felt it unfair to expect them to enter into military service after having been forcibly relocated and detained. Regarding the second question, many internees — particularly those born in the U.S. — were confused as how they could forsake allegiance to a foreign power they never had allegiance to in the first place. Men who answered “no” to both questions, despite fears that a negative response would invite harsher treatment through the presumption of anti-American sentiment, were referred to as “No-No Boys”, popularly explored in the book by the same name by John Okada. Their fears were justified: most “No-No Boys” were subsequently detained in federal prison.

Although the legality of internment was upheld by the Supreme Court in both instances, Hirabayashi and Korematsu’s charges were ultimately vacated in the 1980’s through a series of coram nobis cases simultaneous to a nationwide movements by Asian Americans to seek redress and reparations for internees. These activists eventually earned an apology and reparations from the federal government for surviving internees, but only 50 years after the camps closed.

(Correction: an earlier version of this post incorrectly summarized that the charges were overturned, not vacated. This outcome is significant because it does not set a precedent that future mass internment would be unconstitutional. Thanks Sean Miura for the catch!)

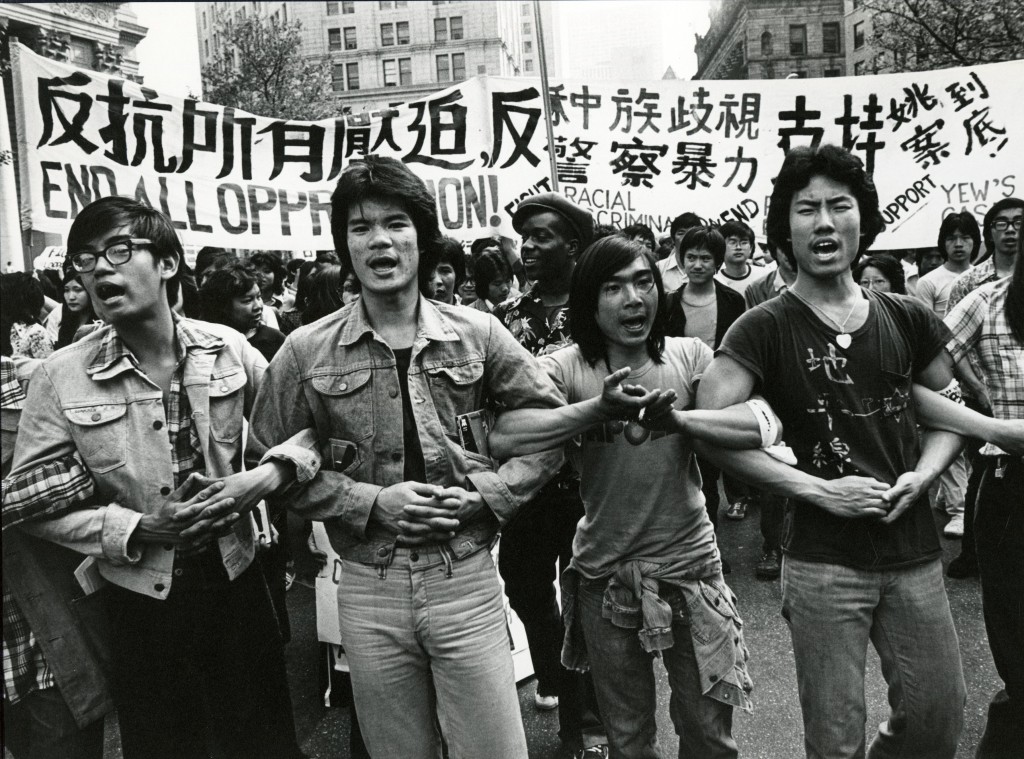

7. The Asian American Movement (1960’s – 1970’s)

The 1960’s was a busy era for civil rights, but Asian Americans are typically unseen in those struggles, often because the second wave of Asian American immigration arrived following the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act. However, for Asian American descendants of laborers who entered the country prior to exclusionary immigration practices, America was their home and the fight for civil rights struck a nerve.

Two of the most well-known Asian American names in the civil rights movement of the 1960’s are Richard Aoki and Yuri Kochiyama, both children whose families were interned during World War II. While many often cite the relationship between these two figures and their work with the Black Panther Party, that fact that they were iconic civil rights workers in their own right is less well-cited. Both worked tirelessly on a number of social justice campaigns, including protests against the Vietnam War, the detainment of political prisoners (e.g. Mumia Abu-Jamal), as well as the fight for reparations for World War II internees. Regarding their work with the Black Panther Party, both Aoki and Kochiyama served as bridges between the African American community and the wholly distinct Asian American Movement emerging at the time.

In particular, Kochiyama’s dedication to multi-ethnic radical work was a central tenet to her activist philosophy: the building of inter-ethnic bridges between disparate racial and ethnic communities through shared experiences. In Legacy to Liberation: politics and culture of revolutionary asian pacific america, Diane C Fujino writes about Kochiyama:

The third theme that emerges from Yuri’s practice is an opposition to polarization. She is a master bridge builder. To counter the creation of artificial boundaries that separate groups, Yuri actively works to connect social issues, movements, and communities…. What Yuri understands in a dialectical way is the [Asian American Movement] brings out the best in people, who in turn, enhance their own humanity by working in the movement for justice.

And later in her own words, Yuri Kochiyama says:

I think today part of the mission would be to fight against racism and polarization, learn from each other’s struggle, but also understand national liberation struggles — that ethnic groups need their own space and they need their own leaders. They need their own privacy. But there are enough issues that we could all work together on… We could all fight together and we must not forget our battle cry is that ‘They fought for us. Now we must fight for them!’

Although among the most well-known of the Movement’s participants, Aoki and Kochiyama were hardly the only Asian Americans working tirelessly on social justice during the 1960’s and 1970’s. Spanning the political spectrum of the Left from progressivism to socialism, a large number of Asian Americans (particularly Asian American youth) created countless groups focused on grassroots community work, including the Red Guard Party and I Wor Kuen. Taken together, the work of the era is referred to as the early Asian American Movement. Movement members not only worked on Asian-specific efforts (particularly in elevating the plight of local Chinatown residents by hosting free clinics and other similar sorts of events), but they also helped advance many larger social justice causes of the era through inter-ethnic bridge-building.

But perhaps the most influential impact of the Asian American Movement was that it introduced to mainstream America — for some it was for the first time — the notion of the Asian American as a radical activist.

8. College Campuses: Asian American Studies and other work (1960’s – present)

Born out of the Asian American Movement of the 1960’s was a struggle that continues even now: the fight to bring Asian American Studies to college campuses. Through 1980’s and 1990’s, countless schools found Asian American students organizing together into groups to create or protect Asian American studies and other ethnic studies programs. Where they have been successful, Asian American studies programs have been flourishing, contributing to the ongoing shaping of the Asian American identity as well as educating successive generations of young Asian Americans on our history. I, myself, am a product of Cornell University’s Asian American Studies program, and my classes on the subject have fundamentally shaped who I am today. Critically, on virtually every college campus where Asian American studies exists, they are a product of the work of student activists.

Both at schools where Asian American studies have been implemented, and at schools where the fight is ongoing, on-campus student groups that came together to promote Asian American Studies remain, not only to protect ethnic studies programs — a fight that is more critical than ever in the wake of state legislation banning such programs in Arizona and California among others — but also to champion other community efforts, both campus-wide and throughout the country. At Cornell, as a student, the group I was part of staged protests to raise awareness about sexual assault against Asian female students, and later worked to address Asian American mental health on-campus. In the 1990’s, Asian American student groups in California organized for better worker rights for Asian garment workers. At Yale, the fight to implement an Asian American Studies programs remains a primary interest of the undergraduate Asian American political student group. Beyond the immediate interests of the Asian American community, Asian American student and associated community groups have widely organized across a number of issues, including in support of affirmative action, to fight the end the war in Iraq, and to allow gays to serve in the military.

Write Diane C. Fujino and Kye Leung in Legacy to Liberation (somewhat mournfully):

Given the socio-political climate, what does it mean to be radical in the 1990’s? The revolutionary fervor that characterized the 1960’s and 70s, with its militant actions and socialist and/or revolutionary nationalist ideology, has dissipated. And while revolutionaries continue to be active in the 1990s, the overall nature of the social movements has changed. Today, the radical wing of the Asian American Movement is chracterized by groups that critique racism and capitalism and seek to transform social institutions, but do not actively work to build a radical working-class movement or to create a socialist state. Still these groups can be identified as radical because their analysis of society and their practice are rooted in systemic oppression, namely, capitalism, imperialism, racism, sexism and heterosexism.

9. Justice for Vincent Chin (1980’s – 1990’s)

In 1982, just two months before I was born, a young Chinese American man named Vincent Chin was brutally beaten to death after his bachelor party by two White men — Michael Nitz and Ronald Ebens — who mistook him for Japanese and blamed him for the recent lay-offs in the Detroit auto industry in which they worked. Despite stalking him from the strip club where Chin got into a verbal altercation with the two men to a nearby McDonald’s, cornering him in the parking lot, and fatally beating him while shouting “it’s because of you little motherfuckers that we’re out of work”, Nitz and Ebens received no jail time, 3 years probation and an insulting $3,000 fine from the state.

Led by feminists and community activists Helen Zia and Liza Chan, the Asian American community in Detroit and around the country were galvanized to stage street protests seeking justice for Vincent Chin. These efforts resulted in federal hate crime charges being filed against Ebens and Nitz, however despite initial convictions against Ebens, the ruling was overturned in appeal. A civil lawsuit also failed to win damages from Ebens and Nitz. In effect, Ebens and Nitz went unpunished for their hate crime.

Nontheless, Vincent Chin’s murder has been a flashpoint event for the contemporary Asian American movement, demonstrating in stark detail the need for collaborative work between multiple Asian American ethnic communities in combating anti-Asian racism. For post-1965 Asian Americans, Chin’s murder was a devastating reminder that the consequences of complacency on this issue could be fatal, and that the justice system is imperfect. Mr. Chin’s life, and the injustices that occurred in the wake of his killing, are still remembered today.

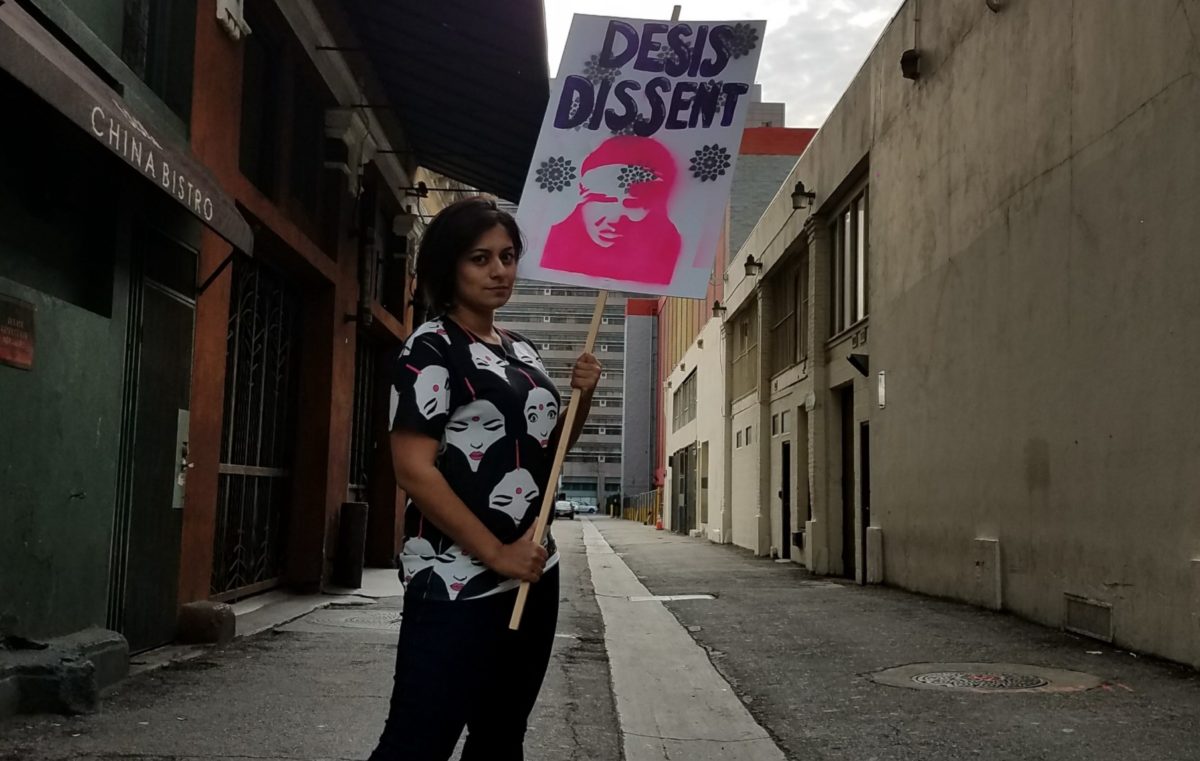

10. Contemporary digital activism (1990’s – present)

Throughout the last twenty years, Asian Americans have situated ourselves at the forefront of digital technology, and have been creatively repurposing the Internet as a political and community organizing tool.

Before Facebook, enterprising Asian Americans built one of the first social networking sites on the Internet: AsianAvenue.com. Later, Asian Americans capitalized on forum/message board technology to improve the platform upon which to discuss our racial identity. Prior to the invention of the word “blog”, Asian Americans built blogs (including this one) to further facilitate racial discourse and community organizing. Two months ago, Asian American feminist Suey Park sparked a massive Twitter debate on Asian American feminism and identity with #NotYourAsianSidekick. To date, the second largest Google hangout (i.e. the largest not organized by President Obama) ever was organized by Asian Americans in remembrance of the 30 year anniversary of the murder of Vincent Chin.

Although some might consider this all online talk, Asian American leveraging of the Internet has had real-world implications. On-the-ground and community efforts (many conducted by these and other fabulous non-profit organizations) are greatly facilitated by Internet word-of-mouth via Asian American online outlets; in the early 2000’s, Asian Americans demonstrated for one of the first times the power of online connectivity for grassroots organizing when it used Internet forum boards and blogs to coordinate simultaneous nation-wide protests of Abercrombie & Fitch stores for selling racist anti-Asian t-shirts. Similar demonstrations since then have been organized by Asian Americans through the Internet, all in the spirit of ongoing resistance to racism, sexism, and other oppression.

Conclusion

Asian Americans have a long and rich history of resistance, including but not limited to the examples cited above. Get your learn on before going out in public suggesting otherwise.

Note: I apologize that this post has had an unintentional Chinese American focus; this reflects the spread of my personal collection of Asian American books, and should not be interpreted as an indication that examples outside of the Chinese American experience do not exist or are not worth noting.

Books Used To Write this Post (i.e. Things I Pulled Off My Shelf in Rage):

- Driven Out by Jean Pfaelzer

- Strangers From a Different Shore by Ron Takaki

- Legacy to Liberation edited by Fred Ho

- Laws Harsh as Tigers by Lucy Salyer

- Unbound Feet by Judy Yung

- Orientals by Robert G. Lee

- Screaming Monkeys by M. Evelina Galang

This list of Asian American resistance is not comprehensive and shouldn’t be taken as such. Have your own favourite example of Asian American political resistance? Please add them in the comments below to continue the discussion!